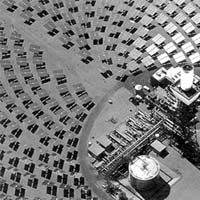

With ample sunlight almost around the year, one possibility is to use of solar energy to generate electricity in apartments and township projects in Chennai, writes Durganand Balsavar Steady strides: Solar Examples of how Solar Power is harnessed and used . House in Canada has solar panels on the roof. Impacted by the global context, Chennai is experiencing dramatic change with ever-increasing pressure from growing populations. Rapid urbanisation has resulted in considerable increase in the use of energy and fuel, consequently polluting atmosphere through the release of toxic emissions. This situation calls for a rapid and fundamental reorientation in our thinking, particularly on the part of planners and institutions involved in the process of urban development. The form of our future built environment must be based on a responsible approach to an ecological balance and the use of the inexhaustible energy potential of the sun. Buildings, in urban areas, are major consumers of energy. It has been estimated that in the US, residential and commercial buildings together use two-thirds of all electricity consumed in the country. While the situation is not as acute in India, increasing demands on urbanisation may push in that direction. The percentage of urban population in India increased from 18.0 in 1961 to 27.8 in 2001. The energy consumption raised threefold, from 4.16 to 12.8 quadrillion Btu between 1980 and 2001, putting India next only to the US, Germany, Japan and China in total energy consumption. There is greater recognition that it is time to take meaningful initiatives in this direction, through creating awareness of what are called 'green' buildings. Solar energy paradigm Solar lamp. With ample sunlight almost around the year, one possibility is through use of solar energy and other renewable energy sources to generate electricity to meet the needs of residential buildings in Chennai. At an urban scale similar initiatives could be undertaken to provide solar powered streetlights and other public facilities. Delhi government has decided to pass an order for compulsory use of solar power for advertising hoardings and water heating in government and some categories of buildings. The order also says that lights of advertisement hoardings shall be powered by solar photovoltaic systems at the cost of the franchisee and conventional streetlights shall be replaced by solar photovoltaic powered ones. Tsunami experiences In Tamil Nadu, renewable energy is now making a gradual impact especially in rural areas. Simultaneously though, its utilisation in urban and semi-urban areas has not yet been growing at the desired pace. Wind energy and solar energy seem to be the most preferred at this stage. Pertinent to mention here is that the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has initiated a programme at the national level assisted by academic & research organisations, solar equipment manufacturers, and funding institutions like the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA). At the State level Non-Governmental Organisations have also, in the absence of infrastructure in rural regions, have invariably relied on solar energy sources. For instance, over the last three years, in coastal Tamil Nadu, affected by the tsunami, several rehabilitation and rebuilding programs were dependant on solar energy for their sustainability. Several temporary shelter enclaves were equipped with cost-effective solar lights and solar fans, in the absence of links to the TNEB network in remote inaccessible areas. The solar street lights are manufactured by companies such as Tata BP Solar. Though the initial cost of investment is relatively higher than the conventional systems, in the long term, in remote rural areas, solar energy has gradually come to be accepted as a more reliable alternative. Solar energy in Chennai Solar street light. If experiments to introduce solar energy are workable in housing settlements in Nagapatinam and Ladakh, a more systematic and concerted effort to explore the possibilities and constraints of introducing such systems in Chennai and other fast growing urban areas is required through the cooperative efforts of the various stakeholders. At a purely theoretical level, the unutilised surface area of the terraces of buildings in the city itself should provide enough incentive to gradually shift to renewable sources like solar energy. In addition balconies also become potential areas to harvest solar power. Even slopped roofs with tiles can accommodate solar panels. The present technology allows for less conspicuous solar array on the roof and they can harvest more energy with less space. In residential developments, the immense potential for use of solar energy equipment exists, through solar lights in common areas and open spaces, gateways, solar fans, solar water heaters and even the possibility of solar cookers in the kitchen. While it could dramatically reduce the consumption of electricity, savings in electricity bills could offset the initial investments. The fact remains that in harnessing it effectively, several initiatives are required.. A nominal solar power backup system UPS that can run 2 lights a fan and a TV can cost about Rs. 28,000/-. These systems have a 20-year durability and a battery life of 3 years. Apprehensions that a cloudy day could mean that there is no solar power need to be allayed.Several solar systems do have back-up energy systems to tide through a few days of cloudy weather. More user-friendly equipment could also facilitate its use on a larger scale. Concerns voiced by environmentalists on the excessive production of photovoltaic solar cells containing silica also need careful examination before deploying the technology. An integrated awareness of the benefits and constraints of solar energy and its sustainability over the long term in conserving and protecting our environment is essential. In order to attain these goals, it will be necessary to modify existing courses of instruction and training, as well as energy supply systems, funding and distribution models, standards, statutory regulations and laws in accordance with the new objectives. The author is an architect practising in Chennai and a visiting faculty at School of Architecture and Planning, Anna University.