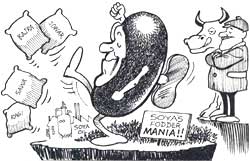

To feed the cattle of the West

FOREIGN exchange, the so-called panacea to Third World economies, has led policymakers in India to install a export-oriented model of development. They want to import development through export, sometimes forcibly replacing traditional activities. The way the oil trade in India has been moulded to make it a medium of earning forex by destroying traditional oil production systems is a case in point.

FOREIGN exchange, the so-called panacea to Third World economies, has led policymakers in India to install a export-oriented model of development. They want to import development through export, sometimes forcibly replacing traditional activities. The way the oil trade in India has been moulded to make it a medium of earning forex by destroying traditional oil production systems is a case in point.

Introducing soya bean to export its de-oiled cakes (DOC) is a good example how the edible oil requirements of the country are thrown to the winds and how the traditional oil seeds and traditional oil production systems are destroyed without caring for the community surviving on them.

Soya bean cultivation has dramatically altered the agricultural map of Madhya Pradesh. The crop has directly affected the production of kharif food grains like coarse cereals, pulses and paddy. Moreover, soya bean is a non-food crop and has replaced the traditional food grains of malnourished people.

Interestingly, even as the government was declaring its intention to be self-sufficient in edible oils, soya bean -- an oil seed with low oil content -- was replacing the more oily groundnut and sesame. When soya bean was introduced in Madhya Pradesh, it was touted as rich in proteins. It was a cruel joke on the malnourished population because soya bean was brought in to be exported.

By virtue of its low oil content, soya bean has the maximum DOC. Therefore, the introduction of soya bean in the state has not been for oil but for DOC. In the '70s, Western countries faced an acute fodder crisis and DOC was thought to be the best diet for cattle.

And that is where soya bean came in. The oil cakes traditionally produced in India contained a lot of fat, unsuitable as fodder. Enter the solvent extraction industry (SEI) to take the oil out of the cakes.

With the entry of SEI, more changes were required. Earlier, sesame was the basic oilseed. It has a high oil content and is easily crushed in traditional systems of extraction. But as the solvent extraction technology had been brought in for DOC and there is negligible DOC in the process of extracting oil from sesame, groundnut cultivation was promoted. And, soya bean, the oilseed with the least oil content, followed in 1977.

Protein for export The government touted soya bean's high protein content when it was introduced, implying that a highly nutrient food was being made available. Since then, ironically, 80 per cent of the soya production has been exported as DOC. Oil is only a "byproduct" obtained in the process of the "production" of DOC, to say nothing of other soya products. It is interesting that although there are 45 factories in Madhya Pradesh working to extract oil from soya beans, there are barely 5 to 6 small enterprises to process soya products. Expanding virtually headlong, soya bean cultivation has started appropriating areas earmarked for pulses and groundnut, the indigenous and traditional rich sources of protein. The cultivation areas for coarse cereals like bajra, jowar, ragi and sawa have also decreased. The total grip of soya bean over the kharif season has changed the agricultural map of the state. And now, the rice bowls of Chattisgarh and Bastar face the same threat.

The monocropping of soya bean has also disturbed the crop rotation system, seriously hampering the process that helps the soil to retain its fertility. As a result, fertiliser use has increased. Monocropping has led to the growth of weeds and pests and the mushrooming growth of the herbicide and pesticide industries. Several multinational corporations are active in the business of agricultural chemicals in the Indore-Bhopal-Vidisha region.

The SEI plants, set up with imported technology, require hexane, which is also imported, to extract oil. If all costs are considered in terms of forex and ecology, it is doubtful whether the government is managing to earn any forex at all through soya bean. How does then one justify its introduction?

Increasing drought and a drinking water crisis in Malwa is also the gift of soya bean, the so-called harbinger of prosperity. The cash crop has increased the purchasing power of landowners, leading to the indiscriminate sinking of tubewells. The exploitation of groundwater is so drastic that the region has been throttled by a water crisis from as early as February almost every year. But according to the state superintending engineer of water resources, K G Vyas, the rapid exploitation is, contrary to all development logic, an indicator of progress. And, presumably, so is the water crisis.

The SEIs need much more energy than the traditional oil production systems which mostly require manual and cattle energy. Also, soya bean has practically no domestic use and totally depends upon outside market forces. Western countries have very little land to cultivate.

Third World providers Holland, for instance, has only 2.4 million ha of cultivable land, but its cattle industry needs 15 million ha of land -- in other countries -- to survive; all these countries are debt burdened, like India, Brazil and Thailand who want to are set their balance of payment right. It is ridiculous that India uses up 3 million ha of its land to feed the cattle of the Western countries while coping with a severe fodder shortage at home.

We should also learn a lesson from what happened in Africa. In 1960, France compelled its African colonies to grow groundnut for its DOC requirement, which resulted in severe droughts from 1968-74 in these countries. Their soil turned into sand, and they are still paying for the consequences. It is high time for us to consider whether soya bean is a boon to Madhya Pradesh or a badge of resurgent neocolonialism.

Akhilesh Awasthy is a freelance writer