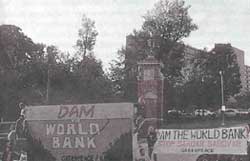

No banking on the World Bank...

NARMADAs and, Tehris have been hogging the limelight in India, while a more dramatic and potentially devastating dam on the drawing boards of a neighbouring country - Nepal -has hardly been heard of here. The name of the dam is Arun in, a project designed to be constructed on the Arun river valley. The dam will be 68 m high, 155 m long, with a 400 mw capacity.

NARMADAs and, Tehris have been hogging the limelight in India, while a more dramatic and potentially devastating dam on the drawing boards of a neighbouring country - Nepal -has hardly been heard of here. The name of the dam is Arun in, a project designed to be constructed on the Arun river valley. The dam will be 68 m high, 155 m long, with a 400 mw capacity.

The size of the project is staggering and the estimated cost is bigger than the annual national budget of Nepal. To put it in perspective, one must also note that Nepal's hydelpower potential is 83 million KW, which is equal to the combined installed hydroelectric capacity of the United States, Canada and Mexico.

The Arun in project struck the headlines in recent months more for the World Banks involvement in it than because of its magnitude. A 1992 internal Bank review had revealed that more than 1/3rd of the projects the Bank has undertaken were failures, and that the deterioration of the Bank's loan portfolio was "steady and pervasive". Another report in the same year submitted by the Morse Commission on the Sardar Sarovar dam had condemned the Bank's project as beset by incompetence, negligence and institutionalised deception.

In response partly to this introspection and public criticism, the Bank established an inspection panel to report to its board of Directors on the problems of the implementation of the Arun in hydroelectric project. The Bank was confronted with a sustained campaign, the thrust of which was that the 100-plus km access road to the dam would cause massive d6orestation and threaten rare and endangered trees and piant fife. The project itself, its opponents pointed out, would displace about 2,700 families and would adversely affect the lives of the 450,000 indigenous people who inhabit the valley. The other criticism was that the Bank's commitment to the dam will "crowd out" public investments in other desperately needed@areas such as education, nutrition, and health.

The Bank set up the inspection panel in September 1993 to investigate issues raised by filed complaints. The complaints, according to the Bank's policy, were to be filed by the people of Nepal, presenting their viewpoints in a collaborative (not individual),capacity. The panel submitted its preliminary report on December 16, 1994, which indicted the Bank's handling of the Arun iii project and stated that it was not in conformity with the Bank's policies on information disclosure, indigenous people, environmental and social concerns.

The bottom line of the report was that the planners of the project did not sufficiently appreciate a number of economically and environmentally acceptable options. The project's execution would have an adverse effect on the country's poverty alleviation prograr@mes and it would cause serious long-term damage to the environment. The drawbacks of the project were truly grave.

The panel's report has ;attracted serious international attention, resulting in deft foot-dragging by the Bank and other donor countries. It hag provoked debate on the status of the WB's panel and the procedures it adopts as an investigative agency.

The Bank's prescription that only citizens of the affected 6ountry could make valid complaints to the panel, and that too collectively, raises the perennial problem of locus standi. Some countries like India and the United States have wrought judicial revolutions through innovative devices like public interest litigation and class action suits, especially in the field of environment.

Environmental NGOS the world over have forged informal but effective alliances to fight against ecologically destructive projects mounted in the name of "development". The campaigns of Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and other NGOS in Japan, the Netherlands and Germany are E2 proverbial. These legal developments deprive the Southern NGOs of the benefits of cooperation and the clout of their better organised Northern environmental crusaders.

An equally debilitating feature is the Bank's obsession with secrecy. It is counterproductive and militates against 2 important facets of democratic governance: transparency and peopie's participation in decisionmaking. The Bank's recent exercises in this direction are too tentative and halfhearted.

---Rahmatullah Khan is professor ofInternational Law at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Related Content

- South Asia macro poverty outlook 2024: country-by-country analysis and projections for the developing world

- Macro poverty outlook 2024: country by country analysis and projections for the developing world

- Double trouble? assessing climate physical and transition risks for the Moroccan banking sector

- Net zero energy by 2060: charting the path of Europe and Central Asia toward a secure and sustainable energy future

- Investing in reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in Uganda: what have we learned, and where do we go from here?

- Toward developing a mobility and gender index