Environment for change

ENVIRONMENTAL degradation, ecological imbalances and sustainability top the agenda of seminars and workshops today. But I have always felt that these discussions are quite superficial. I would like to share my experience and views on sustainable agriculture as a woman farmer. I stress upon the term woman farmer, because I am surviving on farming and practicing sustainable agriculture, and my colleagues of the Shetkari Mahila Aghadi do not have any other source of income apart from agriculture.

ENVIRONMENTAL degradation, ecological imbalances and sustainability top the agenda of seminars and workshops today. But I have always felt that these discussions are quite superficial. I would like to share my experience and views on sustainable agriculture as a woman farmer. I stress upon the term woman farmer, because I am surviving on farming and practicing sustainable agriculture, and my colleagues of the Shetkari Mahila Aghadi do not have any other source of income apart from agriculture.

In such conditions, the risk of experimenting becomes higher, because in case of problems, the financial burden is carried entirely by individuals and not by institutions, as happens when the non-governmental organisations (ngos) undertake such experiments. But I still feel that it is important for the women farmers themselves to carry out these experiments, so that we can solve the problems and help change agricultural practices.

But first, I would like to discuss historically, the evolution of our village economy. During the colonial period, agricultural products and raw materials were bought cheaply by the rulers, mostly by force, and exported for processing, as was the case with cotton. Naturally, agriculture-based rural industries suffered. The bara balutedar, or jajmani system (a caste-related social structure of village artisans) was also destroyed (though to some extent, the rigidity of the caste system was admittedly responsible for this). With the production centers vanishing, people lost their livelihoods.

Before Independence, the villagers had some control over land. They were then surviving on common lands. This was later gobbled up by the colonial industrial centers and their representatives, like the East India Company.

National planning after Independence did not favour village economy and agriculture. The production units in the villages were further destroyed. The agricultural sector and the villagers remained impoverished. Local political bodies, like the gram panchayats, lost their powers. Under centralized planning, the village and taluka markets lost their importance. Villagers had insufficient purchasing power. Ministries and secretariats mushroomed; the district officials became all-powerful. Only government servants and businessmen in the cities had purchasing power.

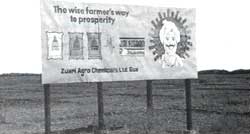

Simultaneously, during the Green Revolution ('60s), the high yielding crop varieties (hyv) were introduced. Irrigation was made available to the farmers. The state provided funds to the agricultural sector for largescale production. But funds were not provided to the farmers and the prices of agricultural products were always forcibly kept low. With the intrusion of hyvs and chemical fertilisers, agriculture changed very fast. Agricultural universities and government schemes taught the farmers to drop obsolete methods. Today, when environmentalists urge the farmers to give up chemical fertilisers and pesticides, the latter are quite likely to retort, "But you were the ones who told us to use them."

On the other hand, in Maharashtra, politics was dominated by the sugar cooperatives. Productivity was affected due to the over-use of water and monocultivation of sugar. Thus, state intervention in the market system also affected diversity in agriculture. Farmers grew crops which were assured price stability. Today, if we want to go for sustainable agriculture, if we want the farmers to change their practices, we should be cautious while experimenting with and propagating new methods.

First and foremost, experimenting with sustainable agriculture should be made viable. Labour costs and agricultural prices have to be taken into account. Largescale production of natural manure is crucial, and they should come easily usable bags. Natural pest control and diversity should also go hand in hand, as in the case of farmers intercropping the insect repelling-mustard plants with general crops.

There should be testing centers in the villages where seeds can be collected and preserved. Various traditional practices of preserving seeds should also be taken note of. All these should be taken out of the university labs and brought to the taluka level. These taluka laboratories should be panchayat-managed. The process should be simplified and made user-friendly for little educated people who live in the villages. And women farmers are capable of handling these.

Lastly, a market for these products has to be created. Stable markets help maintain diversity. People should be ready to pay the prices for good and hygienic products. And I believe they can easily do so, instead of wasting money on potato chips and Coca Cola.

Related Content

- Urban adaptation in Europe: what works?- implementing climate action in European cities

- The state of the world’s human rights 2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding violation of environmental norms in the construction of a hospital complex, Barasat, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, 22/04/2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding sand mining in Jharkhand, 22/04/2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding encroachments on parts of river Odhani, Banka district, Bihar, 18/04/2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding non-compliance of environmental norms by Ashapur Meinchem, village Rowale, district Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, 15/04/2024