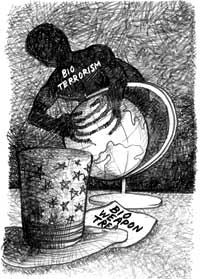

Shaken but not stirred

the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (bwc), banning biological and toxin weapons, has reached a stalemate with the us proposing the termination of the ad hoc group (ahg) at the Fifth bwc Review Conference that was held in Geneva from November 19 to December 7.

the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (bwc), banning biological and toxin weapons, has reached a stalemate with the us proposing the termination of the ad hoc group (ahg) at the Fifth bwc Review Conference that was held in Geneva from November 19 to December 7.

Ironically, despite the September 11 terrorist strike in New York and Washington and the subsequent anthrax scare, the us continues to remain a dissenter. The lack of consensus has come about as a result of differences on the phraseology of the final declaration or any document listing measures to strengthen the bwc. Avis Bohlen, assistant secretary of state for arms control, recently told a un forum that the events had "reinforced our view' that verification was not possible.

Earlier too, in July-August 2001, the 24th session of the ahg ended in disagreement because of the us pullout from the negotiations. The ahg is a body created by a special conference in 1994. It has been given the mandate to formulate a protocol to strengthen the bwc. America rejected the proposal primarily for its perceived inability to nail the "rogues', at the same time leaving the domestic biotech giants vulnerable to intellectual property theft. It feared that the bwc could "put national security and confidential business information at risk without catching wrong-doers'.

For the past six years, the ahg has been striving hard for a draft proposal that could be a legally binding instrument to strengthen the bwc. Several contentious issues have been narrowed down to six areas: definitions, declaration, follow-up after submission of declaration, measures to strengthen the implementation of Article iii (on transfer of technology) of the convention, investigation and legalities. There are 162 signatories to the bwc, of whom 144 (including India and the us) have ratified it.

Prior to the fifth review meet, a breakthrough appeared to be on the cards when the us put forward its seven-point plan through John Bolton, under secretary of state for arms control and international security. It sought to enact strict national criminal legislation, an effective un procedure to probe suspicious outbreaks and use of pathogens, and a code of ethical conduct for bioscientists, among other things. However, these measures could not suitably replace the draft protocol. They also fell short of providing an international implementation body and verification systems that would be vital for giving teeth to the bwc. Member parties have, therefore, adjourned the conference till next year to avoid a complete breakdown in the negotiations process.

India has made considerable contribution to the bwc talks and has stood for a non-discriminatory international treaty. It maintains that any agreement should not hinder scientific research, industrial development and economic cooperation. India proposed a three-fold strategy at the fifth review meet with national as well as multilateral components such as "strengthening the convention in accordance with the 1994 mandate', enhancing "national controls' on production, acquisition, storage, handling, transfer and use of dangerous pathogens, and "bolstering international cooperation and assistance'. India's facilitator for the negotiations, Rakesh Sood, reveals that a mutually acceptable text has remained out of reach.

India's concern on the issue has to be seen in the context of the threat of bioterrorism in South Asia, where many non-state players are said to possess bioweapons. The us has admittedly identified five parties to the meet