Pesticide plot

IN FEBRUARY this year, Down To Earth published a cover story on the unusual cases of deformities in Padre, a village in Kasargode district, Kerala ('Children of endosulfan', Vol 9, No 19). The story was corroborated by a detailed study carried out by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) on samples collected from the village. The results were alarming. All samples contained high levels of endosulfan, an organochlorine pesticide that has been banned or restricted in many countries. Since the mid 1970s, the Plantation Corporation of Kerala (PCK) has been spraying endosulfan from the air on its cashew plantations. The Endosulfan Spray Protest Action Committee - a local pressure group - has worked hard to build public awareness through the media about the health impacts of the pesticide. The government has been forced to take notice, much to the anger of the powerful pesticide lobby.

IN FEBRUARY this year, Down To Earth published a cover story on the unusual cases of deformities in Padre, a village in Kasargode district, Kerala ('Children of endosulfan', Vol 9, No 19). The story was corroborated by a detailed study carried out by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) on samples collected from the village. The results were alarming. All samples contained high levels of endosulfan, an organochlorine pesticide that has been banned or restricted in many countries. Since the mid 1970s, the Plantation Corporation of Kerala (PCK) has been spraying endosulfan from the air on its cashew plantations. The Endosulfan Spray Protest Action Committee - a local pressure group - has worked hard to build public awareness through the media about the health impacts of the pesticide. The government has been forced to take notice, much to the anger of the powerful pesticide lobby.

It was by July that events had came to a boil. First, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) took suo motu action and issued notices to the chief secretaries of the cashew growing states of Kerala, Karnataka, Goa as well as the Union ministries of agriculture, health and the director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) asking the agencies to reply within four weeks. In response to this notice, ICMR set up a three-member team headed by H N Saiyed, director of the National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad, to conduct a detailed study of the area. The team visited Padre in early August. In the meantime, the work of the state government appointed committee headed by eminent engineer, A Achuthan, set up as early as February, gained momentum.

In early August, with the pressure mounting , the district magistrate of Kasaragod passed prohibitory orders against spraying saying, "I am convinced that it is necessary in pubic interest to prohibit the PCK from aerial spraying of insecticide in the area forthwith considering the topographical disadvantages, high degree of inhabitations and incidents of unusual health problems in the areas adjoining the cashew plantations, until the result of the study being conducted is known."

The chief minister, A K Antony, backed the decision announcing publicly that his government was banning endosulfan in the state till the Achuthan committee submitted its report. And in September the Union health and family welfare minister, C P Thakur told newspersons that the Centre has also decided to ban spraying of endosulfan in Kerala. The decision, the press reported the minister saying, "was based on prima facie inquiry which indicated that the insecticide may be the casual agent of the numerous cases of cancer, disorders detected in Kasaragod."

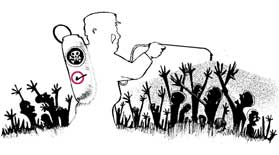

In the meantime, the pesticide lobby launched a virulent disinformation campaign with twin aims; to discredit the CSE study and to prove that endosulfan is safe and harmless. In June 2001, S K Handa formerly head of the division of agricultural chemistry at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), New Delhi, wrote an article in the periodical Agiculture Today alleging that CSE's study was "questionable", "pseudo-scientific" and done with the "motive to get the product banned in the country."

Handa soon became the preferred quote of the pesticide lobby. With the Pesticide Manufacturers and Formulators Association of India (PMFAI) and its president Pradeep Dave leading the pack. Speaking to the daily Business Standard, Dave's simple view was that the "endosulfan issue has been exaggerated." Going on to use Handa, he had strong words for CSE, "agricultural experts (note the use of plural) have found the CSE study to be inaccurate, contradictory in itself and results misleading." Dave then went on to question CSE's capabilities saying condescendingly "testing environmental samples for pesticide residue require special knowledge, training and expertise."

It is another matter that both these knowledgeable gentlemen - a scientist and a pesticide producer - have absolutely no clue of CSE's laboratory capabilities. Or the fact, that however hard these gentlemen may try, they cannot find any scientific inaccuracy in the report. But then who cares. The issue is to use science and scientists to confuse and discredit the evidence.

What is amazing is their blatant and rather tactless manner. In February, PCK had written to CSE saying that while they were concerned about the findings in the CSE report they would like another study, this time by a "reputed test centre". CSE wrote back welcoming the move but asked that PCK must ensure that samples are collected from the villagers in public, that the entire report with its complete analysis method is made public and that the exact location of the samples, including names of individuals are clearly indicated. CSE pointed out that this is what it had done.

But clearly, motives were not so transparent. The PCK commissioned the Frederick Institute of Plant Protection and Toxicology (FIPPAT), based in Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu, at a high cost of Rs 7 lakh, according to press reports. But strangely - or not so strangely - the report was released by the pesticide association, PMFAI at press conferences in Calicut and Thiruvananthapuram where selective extracts were reproduced for the press.

Again, not surprisingly, the report - or should we say extracts because the report is still not available - says: "results of residues of blood samples from the subject showed no residues in endosulfan alpha or Endosulfan beta and endosulfan sulfate." Some small residue of endosulfan was detected in soil and leaf samples. But everything is fine, was the message. The report does not reveal any details about the methodology used or the collection of samples. The villagers of Padre say the samples were never collected from their village. But the Frederick Institute keen to clean up completely, declares that it had concluded that the "causative agent of congenital anomalies reported from the village was not endosulfan". Dave who released the extracts to the press was quick to cash in, "the analysis by FIPPAT is foolproof," he claimed

But the villagers are not convinced. "Just like the aerial spraying about which local people were not informed, this study has also been done secretly," says Srinivas Naik, a panchayat member of Padre.

But the pesticide lobby is willing to give up.

The other part of the strategy is to show that endosulfan is safe. The constant refrain of industry is:

• Endosulfan has been used in more than 60 countries for over 30 years;

• Endosulfan is one of the safest pesticides used in agriculture; and

• Endosulfan does not cause cancer or congenital physical deformities or affect the DNA.

Instead, the pesticide association would like to put the blame for what they call "strange diseases" on inbreeding - "many of those affected by these maladies are reported to be related to each other" says one of their members. Similarly, on background radiation - at the press conference called by the association on August 14, 2001, copies of articles on environmental impact of radiation were not so subtly distributed. During the press conference, this association offered many explanation, "it could be microbiological contamination of water in streams. Or heavy metal contamination. Or poor nutritional levels." In other words, anything else under the sun. But not endosulfan. "We know it is safe," says ringmaster Dave.

Even more callous is their response to the fact that endosulfan is not just used, but that it is sprayed from the air in densely populated regions. The CSE report had pointed out that what was most alarming was the presence of endosulfan in the village wells and stream - the only source of drinking water in the area - clearly, found there because of aerial spraying. E V V Bhaskara Rao, the director of the National Research Centre for Cashew, says proudly - and shamelessly - "research conducted in the early 1970s had concluded that aerial spraying of endosulfan, which is the best pesticide for cashew, was the most economical method." Dave, who clearly would have no problems in living under the aerial sprays, is quick to defend this, "PCK sprays the insecticide twice a year from 20 metres above and hardly 18 per cent of the material goes down."

What is truly shocking is the constant denial. There is just no attempt to acknowledge that a problem exists and that something needs to be done for the villagers suffering from what is clearly a human tragedy of enormous proportion. For years, Y S Mohana Kumar, a doctor in Padre village and farmer-journalist Shree Padre, had approached many organisations to get to the bottom of the deformity cases in their village. But nobody listened. Even today, they would prefer not to listen.

We present for the readers of Down To Earth a reproduction of Handa's article and Bhaskara Rao's follow up which was circulated by the PMFAI at their press meeting in Calicut as well as a response from Padma S Vankar, under whose guidance the samples were tested at CSE's pollution monitoring laboratory. We leave you to judge where the stink emanates from.