Over production of enzyme triggers dengue

dengue took a heavy toll on India in mid-2006 (see box: Sting in the tale) Aedes mosquito is the carrier of this virus, but the ailment assumes alarming proportions due to an enzyme metalloproteinase, notes to a paper published online on October 6, 2006, in embo, a sister publication of the journal Nature. E xcess production of this enzyme causes extensive damage to the body.

dengue took a heavy toll on India in mid-2006 (see box: Sting in the tale) Aedes mosquito is the carrier of this virus, but the ailment assumes alarming proportions due to an enzyme metalloproteinase, notes to a paper published online on October 6, 2006, in embo, a sister publication of the journal Nature. E xcess production of this enzyme causes extensive damage to the body.

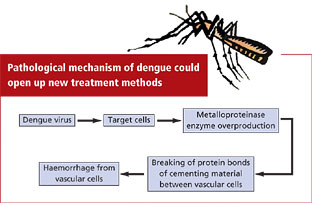

This is exactly what dengue attack triggers. Metalloproteinase attacks the walls of the blood vessels leading to their rupture and severe haemorrhage. The enzyme in higher concentrations acts as biological scissor and destroys the protein bonds which keeps cells together.

"Low concentration of the enzyme is present naturally in organisms that were studied. It is involved in the reconfiguration of organ tissues during human embryonic development or tissue repair.It is also involved in the development of certain cancers. When in excess, it specifically attacks the intercellular cement that binds the vascular walls,' said a statement released by the France-based Institute de Rocherche pour le development, which conducted the study.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne disease caused by a virus of the genus flavivirus. So far, neither the mechanism of action of the virus, nor what leads to the haemorrhage was known.

The research team, through in vitro experiments, showed that dengue-virus infection of certain targeted cells (dendritic cells) of the immune system triggered an inflammatory reaction, stimulating these target cells to overproduce metalloproteinase.

The quantity of enzyme produced is proportional to the concentration of viral particles present, the study noted.

Breaking bonds To verify whether metalloproteinase were the only agents responsible for the breaking of the protein bonds and the resulting increase of permeability, the researchers performed tests on cell cultures of endothelial tissue (tissue lining the blood vessels), of the same type as that of the blood vessel walls. The supernatant (liquid decanted from cell cultures) of the infected cells, containing the metalloproteinase, were brought into contact with this tissue.

The permeability of the blood vessels estimated by the quantity of supernatant liquid passing through the endothelial tissue, appeared significantly higher. The vascular tissue had a natural permeability, which increased when the protein bonds were broken. This natural permeability of the tissue was restored when a specific inhibitor of the enzyme metalloproteinase was added to the supernatant.

Microscopic images of proteins of the intercellular cement, subjected to the action of the same supernatant, revealed that metalloproteinase acts on the blood vessel walls and destroys the protein bonds which keep the cells together. This was, however, neutralised by specific metalloproteinase inhibitors.

Hope for others A series of in vitro experiments following the same principle confirmed these hypotheses. A mouse model with blood circulatory system coloured blue was injected with supernatant containing these enzymes, on their own or in the presence of their inhibitor. This procedure reproduced the mechanisms of vascular rupture that originated blood leakage.

The unearthing of the pathological strategy of the disease could now open up new methods of treatments for not only dengue but also other haemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola.