Our wilds, their homes

There are several international systems for designating protected areas. The most widely used is that of International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) management categories. which include eight classes: (I) Scientific Reserve/Strict Nature Reserve; (II) National Park; (III) Natural Monument/Natural Landmark; (IV) Managed Nature Reserve/Wildlife Sanctuary; (V) Protected Landscape or Seascape; (VI) Resource Reserve; (VII) Natural Biotic Area/Anthropological Reserve; and (VIII) Multiple-Use Management Area/Managed Resource Area.

There are several international systems for designating protected areas. The most widely used is that of International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) management categories. which include eight classes: (I) Scientific Reserve/Strict Nature Reserve; (II) National Park; (III) Natural Monument/Natural Landmark; (IV) Managed Nature Reserve/Wildlife Sanctuary; (V) Protected Landscape or Seascape; (VI) Resource Reserve; (VII) Natural Biotic Area/Anthropological Reserve; and (VIII) Multiple-Use Management Area/Managed Resource Area.

In general. the categories under the higher-end numbers permit or tolerate a greater degree of human access. In addition. there are two international conventions for pro- tected sites: the World Heritage Convention for areas of "outstanding universal value" (not necessarily biological value). and the Ramsar Convention for Wetlands. Although not an international convention. UNESCO's "Man and the Biosphere" programme designates biosphere reserves. In most cases. the human component is thought to be vital for the functioning of a biosphere reserve.

In addition to these international systems, nations have their own criteria for protection of areas under national laws. with a range of conditions from strict protection to controlled use. For example, in addition to national parks, India has designated sanctuaries, game reserves and closed areas under its Wildlife (Protection) Act. Under the Indian Forest Act, designated forests include reserve forest, village forest and protected forest.

The US Wilderness Bill (1964) regards wilderness as "an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain". This view of wilderness is apparently a driving force behind the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) of the World Bank (WB), which has a "Wildlands Operational Note- to govern the framework for protected areas project. However, a GEF project for the Congo, with the deceptive title "Wildlands Protection and Management" will manage reserves with existing large human populations engaged in farming, intensive hunting, timber extraction, and even gold mining and oil exploration. Yet, conservationists continue to ignore or play down past and present use of tropical forests in an effort to attract funding from the propo- nents (now notably the WB) of classic yellowstone-style large national parks and wilderness areas.

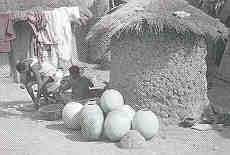

The most relevant and detailed criticism of the 'wilderness myth' comes from A Gomez-Pompa and A Kaus, who suggest that "the concept of wilderness as untouched or untamed land is mostly an urban perception ...the habitants of rural areas have different views of the areas that urbanites designate as wilderness, and they base their land-use and resource management practices on these alternative visions. Indigenous groups in the tropics, for example, do not consider the tropical forest environment to be wild; it is their home" (BioScience, 1992, Vol. 42, pp 271-279).

Related Content

- Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on performance audit of protection, conservation and management of wildlife sanctuaries in Gujarat

- Project tiger: 50 years of tiger conservation in India

- Skin and bones: tiger trafficking analysis from January 2000–June 2022

- Summary for policymakers of the thematic assessment of the sustainable use of wild species

- The critical need for elephant reserves

- Skin and bones unresolved: an analysis of tiger seizures from 2000-2018