Kani vs Kani

"We are now documenting the tribal medical knowledge and details of the medicinal plants that the tribals use," says Vishwanathan Nair, director, KIRTADS. A PhD in tribal medicine, Nair says he refused to publish his thesis as he first wanted to know what the tribals have got. He also fears that any private firm might grab the tribal knowledge to make profits once the information is out as a book. There is no law to share benefits with tribals, he indicates. Nair's fear means that tribal knowledge will remain canned till a 'brave new world' dawns and the system sheds the red tape. High hopes.

"We are now documenting the tribal medical knowledge and details of the medicinal plants that the tribals use," says Vishwanathan Nair, director, KIRTADS. A PhD in tribal medicine, Nair says he refused to publish his thesis as he first wanted to know what the tribals have got. He also fears that any private firm might grab the tribal knowledge to make profits once the information is out as a book. There is no law to share benefits with tribals, he indicates. Nair's fear means that tribal knowledge will remain canned till a 'brave new world' dawns and the system sheds the red tape. High hopes.

Bureaucracy still haunts him. CSIR's Regional Research Laboratory (RRL) in Thiruvananthapuram, in collaboration with KIRTADS, had identified some effective herbal formulations based on tribal knowledge. "The results were exciting," says Vishwanathan Nair. RRL scientists note that one of them, an anti-diabetic formulation, proved to be more potent than a popular allopathic drug. But work on this front was discontinued at RRL following the transfer of a scientist working on it. There is also a fund crunch. "We have discontinued research as we do not have adequate humanpower," says Vijayan Nair, director, RRL. So much so for governmental drug development.

Yet, KIRTADS' former partners have differences with TBGRI's unconventional, market-friendly style. "Please do not involve us in it. We have nothing to do with pseudo-science," said A D Damodaran, former RRL director and well-known scientist in Kerala, commenting on the arogyapacha- based drug. In a telephonic interview, he refused to compare or link RRL's work on tribal medicine with that of TBGRI.

KIRTADS and TBGRI had unproductive interfaces through the 1990s. True to form, both the institutes turned down offers from each other to work alongside. Vishwanathan Nair says that in 1996 at a high-level meeting, KIRTADS' help was sought to organise Kanis and cultivate arogyapacha for commercial drug production. According to reports, the idea was to involve 1,000 families for cultivation in 2,025 hectares in tribal holdings. "They wanted pubic (forest) land, and the adivasis labour to make profit for a private company which has a monopoly," says Vishwanathan Nair. He refused. "I said I would not do a contractor's Job."

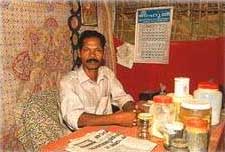

In July 1995, TBGRI scientists accused KIRTADS of trying to torpedo the arogyapacha project. "It is a clash of petty egos," alleges a TBGRI scientist. The Kanis do not have a role. While KIRTADS director Nair insists that the tribal medical knowledge should not be diluted by crass commercialisation, TBGRI scientists accuse KIRTADS of a "totally unscientific" practice of pro moting tribal healers. TBGRI and KIRTADS: the twain shall never meet.

It is a power game which excludes Kanis. In 1995, KIRTADS had sought from the government the power to screen all who approach Kerala's tribal healers. It was not given. An innovative, state-level bill has been drafted with KIRTADS's help by K Abdul Latheef, former faculty member of National Law School of India and joint coordinator of Kerala Environment and Human Rights Research Centre, Kozhikode. It gives exclusive rights to tribal communities over their intellectual property.KIRTADS has been pushing this draft since 1995. But the legislators are not interested.

The well-intentioned draft envisages that a tribal intellectual property rights (IPRS) council with judicial powers will oversee actions to prevent 'exploitation' and 'misuse' of tribal IPRS. Provided the bill becomes law, an infringement of tribal IPRs could lead to four years' imprisonment and a fine of Rs 500,000. Experts, however, note that the tribal IPR law may not work at the state level. "Constitutionally, it is under the jurisdiction of the centre," says B K Roy Burman, an expert on tribal IPR issues and a visiting fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi.

The story of arogyapacha is that of a bold experiment faltering due to unrelenting bureaucracy and a policy vacuum. "The irony of the situation is that TBGRI, the Forest Department and KIRTADS are all part of the same state government, among whom there is no coordination or even a mechanism for dialogue," notes R V Anuradha, a New Delhi-based lawyer who submitted a case-study of this benefit sharing system to the CBD secretariat. The story of arogyapacha also illustrates how various government institutions try to push their own agenda in the name of an ethnic community.

India's tribal communities have a veritable gold-mine in their traditional knowledge. But the governments do not have a clue about its proper use. Bureaucrats will wait till kingdom comes before they let innovations based on tribal knowledge open for public good. If the knowledge is lost by the tribal communities, its fate is sealed in government files.

That the ancient sage Agastya disarmed Kanis and gave them medicinal knowledge is myth. But that the bureaucracy will not let them benefit from this knowledge is reality.