Job chances decline for factory workers

TECHNOLOGY evolves so fast that the shelf life of job skills now rarely exceed 10 years. Automation and rationalisation have pushed entire categories of manufacturing operations, such as machine tools, away from the Western labour market. All over the developed world, companies are being forced to get more work out of fewer people in order to become more efficient.

TECHNOLOGY evolves so fast that the shelf life of job skills now rarely exceed 10 years. Automation and rationalisation have pushed entire categories of manufacturing operations, such as machine tools, away from the Western labour market. All over the developed world, companies are being forced to get more work out of fewer people in order to become more efficient.

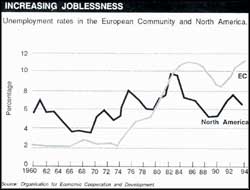

The tremors are being felt most in Europe, where unemployment has been growing at an average rate of 9 per cent for the past five years. In recession-plagued Western Europe, more than 20 million workers are idle.

High unemployment The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development says by the end of 1994, 8.25 million people in the US and 1.7 million in Japan would be unemployed, but in the European Community (EC), the figure would be 23 million, or 11.9 per cent of the work force. And, even this prediction is based on an economic recovery in the EC beginning next year.

Governments are trying to boost employment rates. At a recent EC summit, leaders of the 12-nation trading bloc pledged to make their workers more competitive by investing in high-tech industries because, with the structural shift in industrialised economies, there are fewer jobs for people who are unable to do complex work. In the coming years, information and knowledge will become vital and computer literacy will be as basic as the ability to read and write.

EC chairperson Jacques Delors has proposed an eight-point plan to spend more on research and development and target at least $50 billion annually on transportation and other public work projects. He also urged that $8.3 billion a year be earmarked for telecommunications, computer and other high-tech industries.

The transition caused by the structural shift will force difficult changes for some, involving frequent retraining, shortened careers and less security. But even for the others, it will mean instability and uncertainty until new opportunities are created.

In Germany's Ruhr Valley, for example, furnaces once used to fill workers' pockets with good, steady wages. The trouble was that no one looked ahead to the day when the steel mills would die. With the technological changes taking place, local residents have become fretful as they know no other work.

Since the late 1950s, the labour force in the region has shrunk from 530,000 to about 100,000 and jobs in the steel industry have dwindled from 220,000 to about 120,000. By 1995, an additional 50,000 to 70,000 jobs are expected to be lost.

The majority of the jobs in the United States, Europe and Japan today are in the service sector and the number is on the rise; more women are in the work force than ever before; there are more part-time jobs and more people are self-employed. The future is definitely less bright for jobs on the factory floor.

Roles for robots Factory floor jobs are being increasingly taken over by robots that can handle even routine chores like welding. The production line in Toyota's recently overhauled factory in Japan is conceptually only slightly different from the original one. The workers here now monitor production data on computer screens while robots assemble thousands of parts into finished cars -- in the correct colours and models.

From now on, more workers will spend their time thinking of ways to meet the changing demands of customers and fewer will be needed to make the actual products.

Lord Eatwell, who teaches economics at Cambridge University says, "Skills are the things that will define international competitiveness. The challenge facing the West is to resuscitate its investment and training."