Trapped in a quagmire

THE KATHMANDU valley, for decades the showpiece of Nepal, is literally gasping for breath in a highly polluted environment. Long-time residents are concerned that the host of problems plaguing the valley will also keep tourists away, thereby losing an estimated US $70 million in tourism-related earnings.

THE KATHMANDU valley, for decades the showpiece of Nepal, is literally gasping for breath in a highly polluted environment. Long-time residents are concerned that the host of problems plaguing the valley will also keep tourists away, thereby losing an estimated US $70 million in tourism-related earnings.

Overpopulation is the popular scapegoat for all the ills of the valley and there is a point to this -- more than 9.5 lakh people are crowded in the 541-sq km valley. By the turn of the century, this number is expected to cross 10 lakh, which means an annual growth of 5 per cent, twice the national average.

Another cause for blame is the haphazard growth of urban settlements at the cost of farmland, forests, wetlands and open spaces, which once characterised the valley. In a 15-year period, 20,320 ha (17 per cent) of agricultural land in the valley was converted to dwelling sites, 1,360 ha of forest cover was lost and open spaces and wetlands have virtually disappeared.

Because infrastructure in the valley has not kept pace with population growth, it has led to Kathmandu's pollution levels rivalling that of Mexico City. About 60,000 vehicles spew an estimated 44,000 tonnes of carbon monoxide, 4,000 tonnes of nitrogen dioxide, 800 tonnes of hydrocarbons and 333 tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the air each year.

The story is equally dismal with water. A 1991 International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) report on drinking water quality in the Kathmandu valley disclosed all samples had coliform bacteria levels exceeding WHO's safety standards, especially during the monsoons when some samples showed contamination excesses of 4,800 per cent.

And the refrain is the same with land. The government's Solid Waste Management and Resource Mobilisation Centre says only half the 168 tonnes of waste generated every day in the valley is collected and, of this, about 22 per cent is non-biodegradable. Central officials admit some of the waste dumped in landfills seeps into the groundwater and contaminates it.

The new deputy major of Kathmandu, Nabindra Raj Joshi, who got elected on promises of making the city cleaner and greener, has ambitious plans to solve the city's problems. Joshi says, "We have already requested people to throw their household waste into the collection bins after 8 pm and before 5 am. We have also requested the Solid Waste Management and Resource Mobilisation Centre to collect the waste daily. Earlier, it used to lie on the streets for a week at least." Whether Joshi's plans will work in a city as chaotic as Kathmandu, is another issue all together.

The problems of the valley are seemingly endless but most of its residents show concern only because they have begun to affect tourism adversely. About 15,000 residents depend directly on tourism for a living and 20 times their number benefit indirectly from it. So if tourists move to an alternative Shangri La, their earnings would drop drastically.

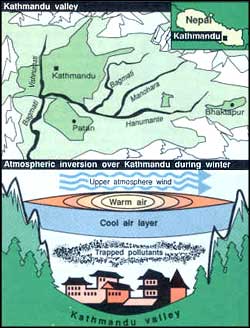

But not all the valley's problems are human-made. Because the valley is bowl-shaped and ringed by towering mountains, Kathmandu suffers from unusually severe atmospheric inversion. Generally in valleys, inversion is responsible for a measure of pollution because the winds cannot sweep air pollutants away. The Kathmandu valley, being bowl-shaped, also suffers from "back radiation", which forces the air to remain stationary over the valley and does not allow pollutants to rise high enough to be blown away.

Back radiation in winter is especially acute, because the warmth of the day creates a halo of warm air over the valley, which traps cooler night air and seals in pollutants. In summer, however, inversion is not much of a problem. Between April and August, warm air cools as it gains altitude. If the rate of cooling is lower than the rate of temperature drop with altitude (referred to in meteorology as ELR or Environmental Lapse Rate), the air rises even higher and pollutants get blown away.

The Kathmandu valley contains three towns --- Bhaktapur, Kathmandu and Patan. An annual population increase of 2.5 per cent throughout the country coupled with scant employment opportunities in the hills is putting increasing pressure on the valley's resources and rapidly adding to its population. In 1941, the population of each of the three towns was only 10,000. Four decades later, the population of the valley had sky-rocketed to 3.63 lakh. By the end of the century, the population is expected to treble and touch the 10-lakh mark. Bharat Sharma, an urban planner with the Nepal government and president of the Environmental Conservation Group, explained why. "We have created a magnet in Kathmandu. Everything is here: infrastructure, education and even jobs." Traditionally, too,, ever since Gorkha King Prithvi Narayan made Kathmandu the capital of a united Nepal in 1769, power has been centred in Durbar Square. Until two years ago, Nepal was an absolute monarchy; today, despite the democratic form of government, power is still concentrated in Kathmandu. So it is not surprising that practically every Nepali dreams of owning a house in Greater Kathmandu (Kathmandu and Patan). According to deputy mayor Joshi, the municipality okays construction plans for 40 houses on a daily basis. Says he, "There was a time when we were approving up to 85 new houses per day. Now, we have temporarily stopped issuing permits on new applications. We don't want to stop them all together but rather try to manage them better." But Joshi agrees that often building laws are broken with impunity. No one in Kathmandu city is allowed to build structures over five storeys high, yet one staff member of the Kathmandu municipality owns a structure which is nine storeys high. Asked about this case, Joshi gives an evasive answer, "If any one goes against the rules then anything can happen."

Sharma maintains urban decay has been going on for decades, but Hans Bjonness, a Norwegian urban planner who has lived since 1970 in Nepal, was less sweeping. "Even five or seven years ago," he said, "things were not so bad." But both concede that even a day-tripper's images of Nepal would include the ubiquitous gas mask, needed to protect lungs from polluted air.

Valley residents are even more exercised by the deterioration in basic services in urban areas. Already Nepal has the highest rate of urbanisation in South Asia with an estimated 3,00,000 people migrating to urban areas annually. The increasing population pressure in the valley is making a shambles of such urban services as potable water, drainage and sanitation. Complained Ajaya Dixit, editor of Water Nepal, "For the last five days, we have not got municipal water. Now, I am buying water. Kathmandu is getting worse every day."

A UN report this year on urbanisation in Nepal lists the main reasons for urban environmental degradation as "unmanaged growth and the inability to adequately meet basic needs of the growing urban population; an increasing number of urban poor without access to basic services, and no specifically targeted municipal or government resource allocation to the poor urban areas."

For all that, Kathmandu is privileged: only 9 per cent of Nepal is electrified, and power-cuts are frequent, but the valley gets power 24 hours a day and power-cuts are a rarity, especially in the tourist season. And, quite literally, tourism is the bottom line in Nepal. In the 1950s, fewer than 100 foreigners visited Nepal annually. Their number has since risen steadily as Nepal became a major tourist attraction in the late 1960s. Now, nearly 1.8 lakh of the 2.5 lakh tourists who land at Kathmandu's Tribhuvan airport every year, head for the valley. For years, planners were able to ensure the valley maintained its traditional charm, which had attracted foreigners in droves. But increasing migration has resulted in the urban sprawl that the once beautiful valley has become.

Addressing the Asian Congress of Architects in 1990 in Delhi, Bjonness noted that though "the problems of squatting on public land and of the homeless living in temples is small in Nepal in absolute terms, it is growing fast and is a serious symptom of a future trend towards a more dependent urbanisation."

Fall in tourist flow

All this will only put tourists off. According to some sources, there was already a fall in the number of tourists in 1991 but a 52 per cent increase in the number of Indian visitors helped the tourism lobby recover their losses.

If tourists start staying away, the valley is doomed, for in the grab for tourist dollars, valley residents even shunned industries. Nepal is one of the few developing countries that has experienced a drop in the industrial labour force. The drop was from 2 per cent of the population in 1965 to 0.6 per cent in 1986-89. But the labour force in the service industry rose from 4 per cent of the population in 1965 to 6.5 per cent in 1986-89. As tourism is the only major service in Nepal, this sector has clearly attracted people from both industry and agriculture.

Pollution of almost every kind occurs in Kathmandu valley. Noise levels hover between 80 and 100 decibels, which is way above international standards.

But noise is only one of Kathmandu's problems. The valley, with 680 km of motorable roads, has a better road network than any other part of the country. But vehicular pollution has increased and a number of drivers wear gas masks. Sharma noted, "Most of this pollution is because of Indians and tourists." Citing the 1,800 Indian-made three-wheelers on the roads that carry about 55,000 passengers daily and belch a large amount of pollutants into the valley's atmosphere. As there are no emission control norms, 20-year-old three-wheelers sputter along adding to the air pollution.

Prem Bahadur Ayar (29), of Baithada in western Nepal, came to Kathmandu in 1976 for a college education. Today he works in the Nepal Electricity Authority. For Ayar, Kathmandu's high levels of pollution make life a nightmare. "Because of my sinus problem I wish I never had to come on to the streets during the daytime," says Ayar. He adds, angrily, "I would like to sue the one who created this mess in the first place." But Ayar cannot escape the streets since his job entails visiting various government offices on his two-wheeler. So he has invested in a cloth mask. In fact, Om Pharma's, the establishment on New Street where he bought the mask from, is doing good business vending Chinese-made surgical masks to Kathmandu's traffic-weary commuters.

The air-quality problem is aggravated by western tourists who have for years been dumping cars here which would fail road fitness tests in their own countries. The money they make easily pays for their stay in Nepal. As Sharma pointed out, this essentially means that the Nepali car-buyer not only pays for the tourist's stay but also has to live with the subsequent air pollution.

Another major worry for valley residents is the highly polluted state of the Bagmati river, which is the valley's only source of drinking water. Dixit summed up the problem succinctly with a vivid label for the Bagmati: "urban flush for the valley".

Discerning visitors to the valley, disturbed by the appalling pollution of air, land and water, often ask, "Why was the situation allowed to deteriorate to this extent?"

For centuries, the three towns of the valley existed separately but linked by a series of villages. Today, Patan is almost a crowded suburb of Kathmandu and Bhaktapur is headed the same way.

The first urban settlements appeared in the valley over 1,500 years ago. Through the ages, the Newars, the valley's original residents, learnt to live in harmony with nature (see box). But space appears to have been the first casualty in the race to convert agricultural land to sites for large, modern buildings. Already more than 40 per cent of the valley's agricultural land has been converted into what has been dubbed "jungles of concrete". And warns Bjonness, such mindless conversion would only worsen an already deplorable situation.

As to why the deterioration went unchecked for so long, Sharma has an answer. "There were a variety of reasons." Until two years ago, he explained, all power was vested in the hands of a few, and they considered urban planning an alien concept. Nevertheless, though six urban development plans were drawn up between 1962 and 1991, their provisions were largely ignored by urban developers and industrialists, often with the connivance of government officials. Shree Govind Shah, a conservationist working with the IUCN, gave as an example the building of a government hospital on the banks of the Bagmati. "When the government violates laws prohibiting construction within 100 m of the river bank, how can the ordinary citizen be blamed?" he commented.

Mecca for migrants

But many of the valley's problems can be traced to the ill-thought adoption of tourism as the path for development. In doing so, not only did the authorities open up a Pandora's box , but they did so ignoring the fact that historically Kathmandu has been a Mecca for migrants from the hills and plains. The rate of this migration continues, even though the figures reveal the percentage of urban population below the poverty line went up from 16.9 per cent in 1977 to 19.1 per cent in 1984-85. The UN report pointed out the obvious: There has been a gradual shifting of the rural poor to urban areas, manifest in the mushrooming of squatter colonies in the valley.

Proposals under consideration to stem migration from other parts of Nepal to the valley include a ban of some sort, even though this would create massive logistical problems and also spawn charges that the planners are creating rifts within the ethnic cauldron that is Nepal. Other suggestions include one from Barbara Adams, an American who has lived in Nepal since 1960, to shift the valley's entire carpet industry elsewhere as this would eliminate a major polluting agent in the valley. However. this proposal has drawn widespread criticism such as from Sharma, "What right do we have to ask people who have lived here for generations to relocate?"

Meanwhile, the Nepal Water Supply Corporation is still soliciting funds to set up a complete solid waste management system.

These and other suggestions may solve some of the problems but, in doing so, they will create others. For example, shifting the carpet industry away from the valley would result in the need to create 30,000 alternative jobs for carpet industry workers unwilling to leave the valley.

Sharma suggests that as the valley has reached the limits of its growth, other "magnet" townships need to be created to lessen the population pressure on the capital. Kamal Tuladhar, a journalist who works for The Rising Sun, and a Newar himself, gives the valley just five years before total disintegration sets in. He agrees with Sharma on the importance of creating alternative growth centres to Kathmandu. As he put it, "The economic opportunities must be taken outside otherwise the cultural, social and economic system of this place will come under tremendous strain and will soon collapse."

Banepa, an old market town on the eastern rim of the valley, has been suggested as a satellite to Kathmandu. Bjonness uses the "living city" concept in supporting the magnet township proposal. "In a living city," he explained, "the original inhabitants are not forced to leave by the degradation of the environment around them."

If the valley is to survive then the authorities need to carefully examine the proposals put forward by Sharma and others. Urban growth which does not take into account environmental factors and the needs of marginalised communities in these cities, can prove to be disastrous. Kathmandu today is an eloquent example of the dangers of blind urbanisation.