Monkeying with money

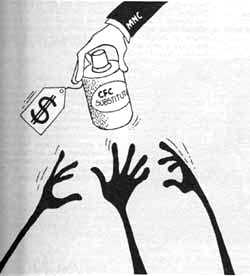

IS THE Montreal Protocol an international treaty committed to the task of protecting the earth"s endangered -- and getting closer to the point of no return day by day -- ozone shield? Or is it a clever trap to hold the developing world captive to those who created much of the mess in the first place -- the multinational corporations (MNCs)?

IS THE Montreal Protocol an international treaty committed to the task of protecting the earth"s endangered -- and getting closer to the point of no return day by day -- ozone shield? Or is it a clever trap to hold the developing world captive to those who created much of the mess in the first place -- the multinational corporations (MNCs)?

Nightmarish doubts like these increasingly taint the dreams of countries like India, now that they have made a commitment as signatories of the Montreal Protocol. They have pledged to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), the cardinal enemy of the ozone layer, by the year 2010.

India received a major jolt in November 1993, when at its Bangkok meeting the Executive Committee of the Ozone Fund, an international body instituted to replace Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS), put on hold its $2 billion programme designed to replace CFCs. The Fund had asked India to look to substitutes.

"India is dual-charging the Fund," alleged Omar E El-Arini, head of the Fund"s secretariat. It is asking for money to phase out the production of ODS while increasing its production, thus categorising the net amount receivable from the Fund as "incremental cost". India has broadened its interpretation of what could be funded.

It appears that the same indignation does not apply to the powerful MNCs. A recent report published in the US journal, Chemical Week, exposes the US"s double-faced policy. It writes that Du Pont has reversed its voluntary commitment to phase out CFC production at the end of 1994, "to prevent possible shortage for automative air conditioning repairs". The US Environment Protection Agency had instructed Du Pont in December 1993 to form CFC "banks" which would be available once production halts in 1996.

"This is not a decision we made lightly," said Joseph Glas, vice-president, fluoro products, Du Pont. "The transition to alternatives has not proceeded as rapidly as we expected." Luckily for Du Pont, it has been granted permission to replenish its coffers by producing its full 1995 allowance of 35 million kgs of CFC-12 under the Montreal Protocol.

Right to choose

The Indian government has not committed itself to any specific CFC-substitute. It is determined to assert its "right to choose". The catch is that a fund-starved country like India can afford to conduct the process of transition only once.

At present, however, the world community appears to be heading towards multiple transition. The first stage requires the manufacturers to switch over to hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), a temporary transition because, according to the regulations laid down by the Montreal Protocol, HCFCs will in turn have to be phased out too.

US companies like Du Pont are pushing HFC134a, of which they are the largest manufacturers. Experts argue that HFC134a cannot be considered a permanent solution because it has a high global warming potential (GWP).

The Indian Government argues that under the duration given to it by the Montreal Protocol, it can wait till an alternative that is sound and stable is available. India"s negligible consumption level renders it a relatively safe-zone, but the North is loathe to admit as much.

Opting for hydrocarbons is another course open to Indian industry. A refrigerator fitted with hydrocarbons has been installed at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, by R S Agarwal. It is currently under observation in the R&D departments of three refrigerator companies -- Voltas, Kelvinator and Godrej. Hydrocarbons do not have either ODP or GWP, and they are available in plenty.

The Indian government wants to ensure that its industrial sector does not remain perpetually dependent on foreign technology to produce alternatives, given that the Indian business community is self-reliant in CFC production.

The Ozone Fund"s message is unmistakeably clear. It is willing to provide money as long as India uses it to buy technology from multinationals which are ready to create new markets for CFC-substitutes.

India has options: take the project developed by the India Institute of Chemical Technology (IICT), Hyderabad, of a chromium-based catalyst and a 2-stage process for HFC134a production. It had a budget estimate of US$ 2.8 million which was deferred by the Fund Secretariat located in Bangkok. The authorities deemed it "ineligible for funding" because it sought to establish a new production facility and not to "replace" an existing plant. However, the Fund agreed to review the project once it evolves a full-fledged policy to fund R&D projects.

India is not the only country that has been rebuffed. China"s attempts to set up a vacuum insulation panel project for domestic refrigerators was skilfully thwarted by the Fund authorities. First, they insisted that the outcome of the small R&D component to be financed by them should become publicly available. When the Beijing government acquiesced, the Fund decided to cut the project cost from $50,000 to $40,000 -- to be met from the equipment component savings from a June 1992 previous project. China has reportedly withdrawn to avoid further complications.

The heads of research institutes and industrialists in India, who are working to phase out ODS, are a worried lot. They know that they have only their own resources to fall back on to accelerate research activities. Already, Sriram Refrigerant and Fertiliser Limited (SRF), the frontline business chemical group in New Delhi, is funding research to develop HFC134a in collaboration with Naveen Fluorine.

Lack of funds

The 2 partners are expected to generate Rs 50 lakh for the implementation of the project."We have already paid about Rs 5 lakh," says R Anand, senior General Manager of Fluoro Chemicals Division. "But our company may not be able to risk the much larger amounts of funds that will be required at the 2nd phase, when the product will be tested for fullscale production."

No official statement on the Fund"s forthcoming R&D policy has as yet been made; but Indian industrialists firmly believe that the position the Fund Secretariat may adopt may not be acceptable. The donors, they claim, may agree to provide funds for R&D, but only under the condition that the country receiving this will not request funding for the licensing of technology from the multinationals. But what if the research crashes? The developing countries can only afford to apply for R&D loans when they are absolutely certain of success -- a matter of considerable unpredictability.

Already, the MNCs are paying hard to get. The company with the substitute technology can set its own price. In any case, the MNCs are refusing to sell their technology to the Indian companies. A leading business group, which is negotiating with several manufacturers, reports that they are willing to part with their know how only on the condition that they are allowed to have majority stakes in the Indian companies.