`Hole` of a problem!

THE 10th anniversary of the Vienna Convention, which led to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, saw more than 100 governments meet at Vienna to continue the struggle to save the ozone layer. The two-week meet led to an agreement to add two new chemicals in addition to the existing ones to be phased out for their negative impact on the ozone layer. These include methyl bromide, an agricultural pesticide and hydrofluorocarbons (HCFCS), primarily used for commercial airconditioning and refrigeration equipment.

THE 10th anniversary of the Vienna Convention, which led to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, saw more than 100 governments meet at Vienna to continue the struggle to save the ozone layer. The two-week meet led to an agreement to add two new chemicals in addition to the existing ones to be phased out for their negative impact on the ozone layer. These include methyl bromide, an agricultural pesticide and hydrofluorocarbons (HCFCS), primarily used for commercial airconditioning and refrigeration equipment.

It was further decided that developing nations should phase out chloroflurocarbons (CFCs) by the year 2010 while the production Of CFCs in the industrialised countries, by far the major producers, is to come to a halt end of 1995. This was a retreat for some developing countries, led by India, who wanted to continue production after,2010 for servicing the existing equipment, like refrigerators and airconditioners. The decision came about after environmentalists and industrialised countries expressed their fear that production in these countries, which was already on the rise, may accelerate further.

This basically means that consumers should stop buying appliances like refrigerators and airconditioners right now. After all, if the life of domestic refrigerators and airconditioners is slated to be 20 years, it will not be possible to get the 'gas' refilled, if required, within 14 years from now, and maybe earlier. Indians also had to accept a tighter export regime by the Protocol as they have been asked to freeze their production at the 1995 level, making it difficult for them to increase exports after the main production centres stop next year.

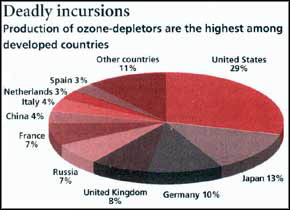

The US and Japan, who were vehemently opposing any phase out dates for HCFCs, also had to back off and agree to 2010 as the final date for phasing out these chemicals. European countries Deadly incursions Production of ozone-depletors are the highest among which do not use these chemicals to a large extent were keen to have an early phase out. Developing countries were given a breather by being allowed to use it until the year 2040, but were asked to freeze their production and consumption at the 2015 levels to prevent producers from taking advantage of the halt in industrialised country production from that year.

The other countries which fought vigourously to prevent a ban on methyl bromide were Kenya and the US. They did not want it to be phased out, though its use has an enormous impact on the ozone layer, many times more than the CFCs. These countries, while ultimately agreeing to a phase out by the year 20 10, managed to slip in exemptions for essential use in agriculture severely diluting its ban.

Russia was exempted from phasing Out CFCs at the end of this year, as agreed in the Protocol, and has been permitted to produce it until AD 2000. However, it cannot export CFCs to Other countries, including developing countries, from next year. Russia was the main accused for illegally exporting CFCs to industrialised countries in recent years, drawing loud protests from the multinational chemical companies like the US-based Du Pont.

The one important area where no legal agreement was signed was the problem of depleting money in the Ozone Fund established to assist developing countries buy alternative technologies to the existing ozone depleting ones. The fund, already too small compared to the demands of developing countries, runs out next year, and hopes for further replenishment for another three years seem dismal in the wake of budget cuts by industrialised countries. USA the largest contributor, already has a bill passed by its Congress, which substantially cuts its contribution to the fund from next year. This distorts the burden sharing mechanism between the industrialised world. European officials are grumbling that the American cuts will make it even more difficult to convince their politicians to not only continue their contributions to a smaller fund but possibly make up for the lost US amount.

Developing countries naively state say if the fund does not provide them money then they are legally not liable to meet the agreed phase-out schedules. Industrialised countries while reducing the size of the fund have never stated that they will not provide money. Instead, they have used various criteria to reduce the kind of projects which can be funded, or the amount of money which can be provided to the developing countries. Therefore, they have significantly reduced the chances of a project even reaching the executive committee of the fund, which has six members each from North and South. Working on reducing the "demand" on the fund rather than restricting "supply", they have closely avoided the political debate on reneging on their agreed obligations until now.

Related Content

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding the presence of a garbage receptacle point/dhalao near a blind school, Delhi, 29/11/2024

- Illicit trading in Africa’s forest products: focus on timber

- Agro-Residue for Power: Win-win for farmers and the environment?

- Agro-Residue for Power

- Antarctic ozone hole has finally started to heal, scientists report

- Look at the sun