Subduing the bulldozer

INUNDATION is nothing new for the Dutch. A good part of the Netherlands -- 25 per cent of it actually -- lies below sea level and would have been inundated regularly had the Dutch not taken steps to keep out the sea. Right from medieval times, dykes, dams and canals have been constructed to manage the flow of water and keep the country dry. About 65 per cent of the country's total area is protected from flooding by dykes. In addition, the level of the land in relation to the sea has been declining at about 20 cm every century.

INUNDATION is nothing new for the Dutch. A good part of the Netherlands -- 25 per cent of it actually -- lies below sea level and would have been inundated regularly had the Dutch not taken steps to keep out the sea. Right from medieval times, dykes, dams and canals have been constructed to manage the flow of water and keep the country dry. About 65 per cent of the country's total area is protected from flooding by dykes. In addition, the level of the land in relation to the sea has been declining at about 20 cm every century.

From the early days, people living near the coast have taken steps to protect themselves from the vagaries of the sea. Before the 8th century, the people simply did not know how to combat floods and so chose to live on higher ground. In the 11th century, the Frisians in the north began setting up settlements on mounds that were built just a bit higher than the high-tide sea level. Today, many of these mounds, known also as terpen, have been flattened, but some can still be seen rising out of the levelled land, with an ancient church or a lonely farm house perched on top.

From the 9th century, people have been digging in Holland, making canals and ditches. Around the same time, large-scale reclamation of peat lands began. Draining the peatbogs resulted in the lowering of the ground level, a process that still continues. The most typical landscape in the low-lying areas of Holland are the polders, low-lying reclaimed areas that are bordered by watersheds in which the water level is regulated.

Aggressive approach

In the 11th century, the passive form of resistance to water was replaced by an aggressive system: dyke construction. Since then, the dyke system has since been extended and improved. Today, Holland has more than 2,880 km of major dykes, but its flank is still protected by a long row of sand dunes.

Despite all the protection measures taken, major dyke breaches occurred in nearly every generation.

With Holland slowly sinking and the level of the sea rising, the southwestern province of Zeeland is especially vulnerable to flooding from the sea. The North Sea, which laps the shores of the Netherlands, swells occasionally in the southwest as a storm surge, pushing the water on to the land. (Storm surges are periodic rises in sea levels that exceed normal high-tide levels). Strong winds literally force seawater to pile up along the coast; the shallower the sea, the greater is the effect of the wind; and, unfortunately, the sea off southwest Holland is quite shallow.

The night the sea came in

On the night of February 1, 1953, the North Sea was roiled to unprecedented heights by a gale that coincided with a spring tide and was more than exceptional in its long duration. In numerous places, the water swarmed over the dykes into the polders.

Churchbells tolled and sirens wailed the age-old warning, "Flee, the water is coming!" About 800 km of dykes were breached or severely damaged, 1,835 people drowned, 50,000 animals were lost, crops were totally destroyed, and 47,000 homes and 133 villages went under the ferocity of the water. More than 200,000 ha of land were inundated. It was one of the worst natural disasters in Dutch history.

But the Dutch have never been a low-spirited lot. "We've still been lucky," some said. "It could have been much worse." And it may have just been worse. If the dykes of the Hollandse IJssel river east of Rotterdam had breached, the whole urban conglomeration of Rotterdam, The Hague and Amsterdam would have been under water.

Even though authorities in the Netherlands were aware that high water levels could occur, they were not prepared for a surge of such magnitude. Just prior to the February 1953 disaster, the so-called Storm Surge Commission had put out a report rating the condition of the dykes as inadequate. However, no repair or preventive work was undertaken because the government was still dealing with various problems in the post-war years.

But after the 1953 storm, the people pressed for quick repair of the damage. It also became very important in the minds of the people that such a disaster must never be allowed to happen again.

Work on closing tidal breaches began rapidly, and by November that year, the last one was closed. In the meantime, a large-scale plan -- the Delta Project -- was proposed to counter storm surges by closing off the main tidal estuaries and inlets in the southwestern part of the country. The idea appealed to everyone. (MAP Pg 269) In 1958, the Dutch parliament passed the Delta Act, which launched the project, involving the closure of all tidal inlets except the shipping routes to Rotterdam and Antwerp in Belgium. The final part of the project was to be a dam closing off the Eastern Schelde (Oosterschelde).

The limits of growth

At the end of the '60s, concern for the environment was growing in the West and it was not long before voices cried out in favour of keeping the Eastern Schelde open to maintain the tidal flow and preserve the natural environment of the area. The Eastern Schelde is a saltwater river and forms a perfect environment for shellfish such as oysters and mussels.

At first, the public works department was sceptical about keeping the Eastern Schelde open. But a debate on "the limits of growth" resulted in a compromise: what would be constructed would be a storm surge barrier with gates that could be closed temporarily, when the tide was too high.

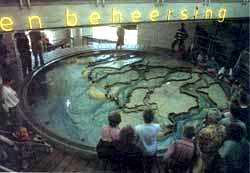

In engineering terms, the Eastern Schelde barrier is a showpiece. Although it resulted in higher expenses, it meets the demands of both safety and nature preservation. The know-how doesn't assist only the Netherlands with its hydraulic engineering problems, but may be of great value to people working on hydraulic projects in Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, Denmark.

After the completion of the Delta Project in 1986, the next endeavour was to continue to strengthen the dykes along the IJssel, Rhine and Waal rivers. The department of public works and water management planned to strengthen and heighten 600 km of dykes by 2004.

Ever since its creation in 1754, the department of public works and water management, with its various name changes, has directed and led the nation's hydraulic works. It was virtually a state within a state.

After the Delta Project, the prestige of the department declined because it began to function as a bureaucratic service, interested only in large-scale works. The dyke reinforcement programme was one that went too far. The department's work was considered by many to be a threat to nature and the landscape.

Making way for dykes

In the early '70s itself, in the picturesque town of Brakel, 180 houses as well as a 19th century town hall had to be demolished -- everything had to yield because the water authorities wanted to strengthen the dykes. Houses were pulled down in other villages, too, and entire tracts were replaced with long, broad walls on which only grass -- not even bushes or trees -- was allowed to grow.

Observers said the new dykes seemed to more suited to stop the ocean than rivers. Parliament condemned the brute force used in Brakel and a commission was formed to investigate the management of river dykes.

The underlying assumption for speeding up dyke improvement was apparently fear. In March 1992, Hanja Maij-Weggen, the minister of transport, public works and water management, told parliament, "I don't want to enter history...responsible for dyke breaches causing deaths and wounded. After 2000, sitting in my rocking chair, I don't want to hear that I was to blame because I didn't look after the dykes."

Ab Van de Beek, a retired doctor, was one of the first to protest against the relentless strengthening of the dykes. In 1992, he wrote in the Amsterdam daily, Parool: "When we had the floods in 1953, we thought the heightening of dykes would be a matter of general interest. But after a while, we discovered that not everyone is equal when houses had to be demolished."

This Becht Commission, set up to recommend dyke improvement, made its proposals, but nothing really changed. "After 1979, the landscape murder continued," Van de Beek said, even though various interest groups, nature lovers, environmentalists and journalists campaigned for an end to the destruction of the landscape.

Another group of people which put pressure on the authorities were not against dykes or their maintenance or strengthening. However, their contention was that fighting against the sea was totally different from controlling rivers. A group of 6 artists presented a pamphlet called Atilla at the Bulldozer - the Department of public works and the riverlandscape. It was an attack on the drawingroom thinking, the omnipresent measuring staff and the bureaucracy. It was a fight against everything or everyone that represented the department of public works and water management.

The department defended its actions, saying that the levels of the rivers were rising. The artists, however, disproved this contention with statistics showing the exact opposite. The department claimed that the heightening and broadening the dykes was necessary to prevent the accumulation of ice floes. But landscape administrators said nothing would withstand ice congestion. As one engineer put it, "The water will keep rising until it flows over a dyke somewhere or a dyke breaches because of the pressure. Dyke heightening is no solution against ice and the forming of ice dams."

Nonetheless, 200 km of dykes were heightened in the early '90s. Dyke improvement was the new catchword and no water authority even looked at the environmental effects. Where more than 5 km of dykes had to be strengthened, public hearings and a report on environmental effects were mandatory before work could begin. To get around this limit, the government simply cut up hundreds of kilometers of dykes into small pieces of 4.9 km each. The Union of Water Authorities justified this act by saying, "Otherwise, it (the whole operation) would take too long."

Winds of change

Finally, it was only at the Rio Summit that things began to change. A Dutch foundation called Save Our Riverlandscape brought to the notice of Earth Summit delegates Holland's use of double standards in its dyke-strengthening programme. It said that though the Netherlands insisted other countries apply international norms in analysing the environmental effects of projects, the Netherlands itself did not practice them. Because of this, the foundation said, "The age-old, unique and world famous Dutch riverlandscape is now being destroyed by dyke strengthening."

Maij-Weggen changed her strong viewpoint and called for an independent investigation. The results of Commission Boertien meant a victory for the opponents of dyke strengthening. The Commission criticised the programme for ignoring and bypassing the Becht committee's recommendations. The Commission Boertien struck a chord with a change in attitude. One of the basic assumptions in its view was: "The Dutch riverlandscape is part of the national cultural inheritance and has to be preserved as a national inheritance."

According to Boertien, dykes can become steeper and more sophisticated without endangering the environment and its report called for using more imagination in strengthening them. In January last year, the cabinet allocated another 210 million guilders to strengthen the dykes and to "save" its characteristic landscape where possible.

For more than 30 years, inhabitants along rivers lived in uncertainty: demolition, clear-felling, house expulsion, bulldozers. Is it finally over?

Last year, the government started pilot projects involve greater public support in bolstering dykes. Interest groups in each dyke area were roped in to be involved in the project and consulted for reports on environmental effects.

Richard Siebers of Save the Riverlandscape is quite satisfied with the recent developments. "The water authorities now have to learn how to deal with democracy. In the past, their attitude was: we know everything." Delegate J van Dijkhuizen of Gelderland province said recently that there has been a shift in thinking. "The politicians have awakened. We, the provincial board, the water authorities and everyone who's working on dykes are forced to do things differently now."

Nanke Kramer is a freelance journalist.