Working children find a home in Bangalore

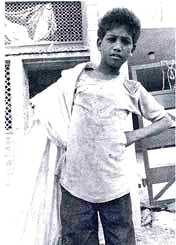

THIRTEEN-year-old Seena is a rag-picker in Bangalore who used to sleep on the roadside and eat at pavement tea-stalls, constantly evading cops who pick up street-children like him and take them to a beggars' colony on the fringes of the city. But now, Seena and others like him need not worry about being rounded up.

THIRTEEN-year-old Seena is a rag-picker in Bangalore who used to sleep on the roadside and eat at pavement tea-stalls, constantly evading cops who pick up street-children like him and take them to a beggars' colony on the fringes of the city. But now, Seena and others like him need not worry about being rounded up.

The Association for Promoting Social Action has built a shelter, Namma Mane (Our house), on the outskirts of Bangalore for homeless, working children. The house, which is run by the Concerned for Working Children (CWC), can accommodate 100 youngsters.

According to unofficial estimates, Bangalore has 45,000 working children, of whom 25,000 are homeless. Most of the children, aged 7 and 14, are migrants from rural areas who have come to the city, alone or with their parents, in search of jobs. According to the Karnataka Slum Clearance Board, the city had 400 slums in 1989, housing nearly 40 per cent of the city's population. Namma Maneopened in early 1992, by July was home to about 25 children. "We do not force anyone to come and stay here," explains K C Venkatesh, a CWC worker who is the "father" of the home and stays there with his wife. "So we have not organised a campaign to fill the home. After all, this is just a model."

Some children leave Namma Mane because it is too far away from their places of work and ohter leave because they find its rules and regulations too restrictive too restrictive. "But CWC has not made any rules -- we have made our own rules," says Fazil Pasha, a 13-year-old who stays at the home. "Bathing daily is compulsory, especially after returning from work. So is changing clothes. We cook our own food, so everyone has to share the work. We don't allow any abuses and everyone has to be back by 10 in the evening."

In Namma Mane, the children are given breakfast and dinner, but they have to do the washing of utensils and chop the vegetables. The children pay Rs 1.50 each for their dinner from an average earning of Rs 20 daily. But, says Venkatesh, "The children tend to spend the money and not save it because they feel very insecure carrying money. They fear the cops will catch them and they will lose whatever they have."

None of the children wants to continue rag-picking -- one wants to be a gardener and another a mason.Pasha adds to his income by mending the clothes of other children for a small fee, using a sewing machine provided by CWC. "I even do things free if someone does not have the money," he said. The children are also encouraged to grow vegetables in their own kitchen-gardens.

The facilities at Namma Mane has is a clinic, staffed by doctors from the city who visit regularly. There are also informal evening classes, but according to Venkatesh, "One has to be careful, for once the children feel they are being taught, they lose interest." So, a number of innovative teching methods,using plays, songs and stories, are emplpyed.

Tough problem CWC was formed in 1978 out of the interaction between the Bangalore Labour Union and unorganised workers. As CWC founder-director Nandana Reddy puts it, the problem of child workers was one of the most serious ones the union encountered, but it was not able to do much for the children. Laws prohibiting child labour did not prevent employers from drawing on this cheap pool of labour.

The children and the union worked together and drafted the Child Labour (Employment, Regulation, Training and Development) Bill, 1985, which was presented to the Karnataka and Central governments in 1985. As a result, the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1985 was passed. But this, according to Reddy, is "a sad dilution of the bill proposed by the children as it does not have any teeth."

About this time, CWC was registered under the Societies Act and Ankur, its field programme with working children in Bangalore,was started soon after. The programme began with eight centres and it now has another 30 centres as well as eight outreach points, through which CWC's support is extended to more than 5,000 children. Meetings are held regularly and rarely do the children miss them.

CWC makes no attempt to reform or correct the children. Venkatesh explains, "Our whole effort is to ensure the children understand the value of organising themselves so that they can fend for themselves. By merely giving some of them a few goodies to eat or some nice clothes once in a while, we cannot achieve much."

CWC's efforts have borne fruit. The children have each started putting aside Re 1 a month in bank accounts opened by the 35 Bhima Sanghas -- associations they have formed under guidance from CWC (See Down To Earth, October 31). The Bhima Sanghas have also succeeded in getting the municipality to construct a road and start a bus service to Namma Mane. Bhima Sangha members can also avail of the free medical facilities provided by the Karnataka government at Ulsoor hospital by showing their identity cards.

But Reddy terms these minor gains. "Though our efforts have had some success, a lot more has to be done," she says. "An important issue is to check migration from rural areas, and also ensure that where migration is inevitable, the children are prepared to face urban conditions."