The Caspian affair

The Caspian region has possibly the third largest oil and natural gas reserves in the world (after the Persian Gulf and western Siberia), estimated to be up to 15 per cent of the total reserves of the world. Hardly any of this potential has been tapped as yet, and it is expected that there are much bigger reserves that haven"t been assessed as yet.

The Caspian region has possibly the third largest oil and natural gas reserves in the world (after the Persian Gulf and western Siberia), estimated to be up to 15 per cent of the total reserves of the world. Hardly any of this potential has been tapped as yet, and it is expected that there are much bigger reserves that haven"t been assessed as yet.

The Caspian region"s introduction to the geopolitics of oil began with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Several smaller nation-states emerged in Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kirgizstan) and the Caucasus (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan). A handful of former communist party strongmen rule the Caspian countries and runs them like fiefs. Some of the biggest oil companies of the world court these oligarchs; and the corporations" mutual interests are conflicting, competitive and overlapping in turns, leading to bitter rivalry alternated with mutualism. In July 2000, there were reports that the US justice department was investigating whether James Giffen, a New York banker and official adviser to Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev, illegally funnelled US $35 million from three oil companies to Swiss accounts of high-ranking Kazakhstan officials, including Nazarbayev.

"I cannot think of a time when we have had a region emerge as suddenly to become as strategically significant as the Caspian," US Vice President Dick Cheney, then the CEO of the oil company Halliburton Corp, told a meeting of oil executives in 1998. In the same year, Bill Richardson, the then US energy secretary, laid out the US interest in the Caspian region: "This is about America"s energy security. It"s also about preventing strategic inroads by those who don"t share our values. We"re trying to move these newly independent countries toward the West. We would like to see them reliant on Western commercial and political interests rather than going another way. We"ve made a substantial political investment in the Caspian, and it"s very important to us that both the pipeline map and the politics come out right."

It is this politics of drawing maps that kept the Caspian region from becoming a major oil and gas exporting area. In Russia, the region has a former superpower to its north. To the east lies China, an emerging superpower. To the east and south lie such politically volatile, strife-torn areas as Chechnya, the Kurd-dominated parts of Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan. Add to this the fact that the most powerful country in the world is directly involved through its business interests or through the presence of troops in the fallout of the war on terrorism. Religious and ethnic unrest has complicated matters further; the region is the mingling point of Christian Europe and Islamic Asia, of the several ethnic peoples of Central Asia.

During the US military campaign in Afghanistan in response to the September 2001 terror attacks, several analysts had pointed out that an important reason behind the US action was securing its oil/gas interests (see box: The Afghanistan files). "Afghanistan"s significance from an energy standpoint stems from its geographical position as a potential transit route for oil and natural gas exports from Central Asia to the Arabian Sea," says the US department of energy"s country analysis brief on Afghanistan.

Pakistan-based journalist and author Ahmed Rashid, who has covered Central Asia for more than 20 years, compared the oil geopolitics to the "Great Game" (a term coined by Rudyard Kipling) between Russia and Britain for the control of Central Asia in the 19th century. In a 1997 article, Rashid called it the "New Great Game", a term that has gained currency. While the 19th century game was between two players and the prize was India and the warm-water ports of the Arabian Sea, the new game has many teams, with players constantly changing sides, aligning, de-aligning, and then realigning.

Is it a sea? Is it a lake?

When it comes to regional matters, perhaps the biggest mess has to do with the ownership of the Caspian Sea, the bed of which is rich with oil and gas. Before 1991, the Soviet-Iranian treaties of 1921 and 1940 regulated the ownership of the sea. But neither side established seabed boundaries or negotiated exploration. No new legal framework or treaty was worked out after the break-up of the Soviet Union, meaning the earlier treaties still govern development rights to the seabed.

The five nations along the shores of the Caspian - Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan - are locked in a bitter dispute over this. It came to a head on July 23, 2001. An Iranian gunboat chased two Azerbaijani oil exploration ships from a disputed oil field in the southern Caspian. This was the most serious flare-up in an uneasy peace. BP oil of the UK suspended all exploration and development activity under its contract with Azerbaijan in the Alov oil field to which Iran has a claim. Russia and the US condemned Iran. Turkey responded in late August 2001 with a show of force by sending fighter jets to Azerbaijan, its ethnic ally. Since then, exploration and development in the southern Caspian has come to a standstill.

It is a different story in the northern Caspian. In August 2002, when Russia held the largest military exercises since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the Caspian Sea, it invited representatives from the four other littoral states as observers. Russia and Kazakhstan have signed a bilateral deal on sharing of disputed oil fields. In the second week of July, the Kazakh energy minister Vladimir Shkolnik was reported to have said that tenders would be invited before the end of the year for some 120 offshore sites. Russia has an understanding with Azerbaijan as well. Iran says such agreements are illegal before a five-way settlement is reached. But all this bickering seems inane in light of the fact that the very status of the Caspian "Sea" is disputed.

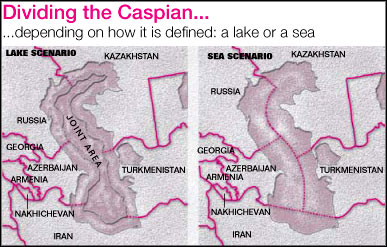

Is it a body of water under the Law of the Sea Convention, which does not cover inland lakes? If so, the full maritime boundaries of the five countries would be based upon an equidistant division of the sea and undersea resources into national sectors. Under this, states would have exclusive rights only to resources lying within 45 nautical miles of their shore. If it were agreed, on the other hand, that the Caspian is not a "sea", then international maritime laws would not apply. Then its resources have to be developed jointly (see map: Dividing the Caspian). Iran is agreeable to dividing the Caspian into national sectors, but on the condition that each country gets 20 per cent of the seabed and surface of the sea. However, if the Law of the Sea were to be applied, Iran would get only about 12-13 per cent. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan want this as they have big offshore oil/gas fields not far from their shores. They oppose Iran"s proposal of dividing the Caspian into five equal sectors. They are in a hurry to strike a deal to be able to exploit their fields. Iran has little oil or gas off its Caspian shore, and is playing a waiting game to maximise its share. Russia and Turkmenistan keep shifting sides depending on which plan - or which variation of the two plans - is more profitable to them. But let us assume that the legal dispute over the Caspian is sorted out. How will the oil and gas be marketed?

Pipeline politics

Anybody who invests billions in extraction of petroleum and natural gas would want the shortest, cheapest route to the most lucrative market. Unlike most major oil exporters of the world, most Caspian nations are land-locked.

Pipelines are preferable to overland and marine tankers, especially for gas, provided the volumes of supply and demand justify the investment. The Caspian region doesn"t have the economy or the market for its oil and gas production capacity. It doesn"t have the investment and technology required to explore and transport oil/gas over long distances. To make the oil/gas reach a market, the pipelines or tankers need to cross international boundaries. This is where pipeline politics extends from economics to geopolitics (see map: Pipeline dreams).

The existing pipelines go north to Russia, already the owner of the largest gas reserves of the world as well as unpaid bills for gas imported from Caspian nations in the past. The rapidly growing economy and burgeoning population of China in the east is separated from the Caspian region by a vast desert pockmarked with ethnic unrest. A pipeline going west to European markets via the Black Sea or the Mediterranean is likely to be too costly and areas such as Chechnya and the Kurdish dominated parts of Turkey don"t inspire too much confidence. Yet work has already begun on a 1,755-km pipeline from Azerbaijani capital Baku to the Turkish port of Ceyhan in the Mediterranean, via Georgia. This is the only pipeline that fits well with US foreign policy. Georgia has used US fears of Iran to settle for the western route because it gains transit fees from the pipeline passing through is territory.

After years of hesitation and mistrust, there were signs that the US and Russia might work together on the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline. Russia announced on June 11, 2002, that it would build a pipeline connection to the Baku-Ceyhan oil route. This would give Russia access to a warm-water port in the Mediterranean for exports. In May, Russian and Georgian officials had announced a joint venture to build a line connecting the Black Sea port of Novorossiisk to the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline.

The eastern pipeline route to China was a matter of speculation till news arrived that China had begun work on the "east-west" gas pipeline. This large project, often compared to the Great Wall and the Three Gorges dam in terms of size, would stretch across a 4,250 km from the recently discovered gas fields in the western deserts of Xinjiang (close to China"s border with Pakistan) to Shanghai in the east. This is relevant to the Caspian nations as they could build a connection to this pipeline and export gas to as far as Japan.

But the most economical access to the sea (and the international market) for Caspian oil and gas is through Iran, a political anathema for the West. Such a route would greatly increase Iran"s wealth and influence in the region, something the US finds unacceptable (see box: Behind the veil). The second most viable route is through Afghanistan to Pakistan and possibly to India. On May 30, 2002, Turkmen, Afghani and Pakistani leaders signed a long-negotiated agreement in Islamabad over the pipeline via Afghanistan. But according to sources in Pakistan, oil companies haven"t shown any interest in the deal due to the situation in Afghanistan. With Indo-Pakistani relations at a low ebb, there is no possibility of a pipeline coming to India through Pakistan. This deters oil companies as the Pakistani market isn"t big enough. The real attraction for the companies is the energy starved Indian market.