Future fuel

oceanographer William P Dillon likes to surprise visitors to his lab by taking ordinary-looking ice balls and setting them on fire. "They're easy to light. You just put a match to them and they will go,' says Dillon, a researcher with the us Geological Survey (usgs) in Woods Hole, Massachusettes. The prop in Dillon's show is a curious structure called methane hydrate. Unlike ordinary water ice, methane hydrate consists of single molecules of natural gas trapped within crystalline cages formed by frozen water molecules. Although chemists first discovered gas hydrates in the early part of the 19th century, geoscientists have only recently started documenting their existence in underground deposits and exploring their importance as a potential fuel.

oceanographer William P Dillon likes to surprise visitors to his lab by taking ordinary-looking ice balls and setting them on fire. "They're easy to light. You just put a match to them and they will go,' says Dillon, a researcher with the us Geological Survey (usgs) in Woods Hole, Massachusettes. The prop in Dillon's show is a curious structure called methane hydrate. Unlike ordinary water ice, methane hydrate consists of single molecules of natural gas trapped within crystalline cages formed by frozen water molecules. Although chemists first discovered gas hydrates in the early part of the 19th century, geoscientists have only recently started documenting their existence in underground deposits and exploring their importance as a potential fuel.

Research on gas hydrates commenced in 1970s, when scientists recognised that hydrates were responsible for the bubbling and hissing in sediment cores brought to the surface during deep sea drilling projects.

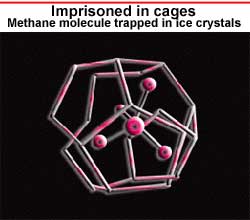

Trapped molecules Natural gas hydrates are ice like crystalline substances composed of cages of water molecules that host low molecular weight gases, mainly methane. These crystalline cages with hydrates generally form in marine sediments when gas concentrations are adequate, temperature is low and pressure is high. It is similar to gas molecule getting imprisoned in clathrate or cage like structure (see diagram: Imprisoned in cages). The gas molecule contains methane, propane, ethane and other hydrocarbon compounds.

Though gas hydrate promise to be the fuel of the future, there is a formidable obstacle to use hydrates as fuel. When removed from its high pressure and low temperature environment hydrate decomposes and releases the hydrocarbon gas contained in it. There are no methods as yet to safely transport large amounts of hydrate to production facilities on land. One new approach to the hydrate transportation problem is to pelletise hydrate or to inflate large bladder-like blimps with hydrate in the deep sea. Submarines could then tow the hydrates to shallow waters near the continental shelf, where they could be slowly decomposed to yield fuel and water.

Seafloor treasure Most known deposits of methane hydrate lie below the seafloor in regions that slope from the continents to the deep ocean basins thousands of meters underwater. Marine geologists have tentatively identified deposits off the coasts of Costa Rica, New Jersey, Oregon, Japan, India, and hundreds of other sites around the globe. Petroleum companies have also encountered hydrates while drilling through Arctic permafrost in Siberia, Alaska, and Canada.

One of the recent intensive research programmes on the gas hydrates, its occurrences and distributions are being carried out under the aegis of the usgs, Geological Survey of Canada and Japan National Oil Corporation Technology Research Centre, Japan. Indian scenario

Formations of gas hydrates in India can be found along the coast off Kerala-Konkan, Mahanadi and Cauvery basin, and the fan deposits in Bay of Bengal have also been identified to be potential gas hydrate bearing zones.

To give it an impetus, under the National Gas Hydrate Programme, the ninth five-year plan (1997-2002) earmarked an outlay of Rs 2,130 million. To strengthen this pursuit, National Institute of Oceanography (nio), Goa has decided to open a centre to promote parallel investigation, says E Desa, director, nio, Goa.

Future prospects

As per a very conservative estimate by usgs, the worldwide amount of methane in gas hydrates is estimated to contain at least 1x104 gigatons of carbon, which is about twice the amount of carbon held in all fossil fuels on earth. "All these estimates are quite uncertain. But it remains abundantly clear that methane hydrates contain the largest store of carbon that we know about that is underground,' says MacDonald, director, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Laxenburg, Austria. He adds, "Given their worldwide distribution and their very large quantities, they make a very attractive energy source, provided that one can bring the gas up at somewhere near market price. '

Currently, groups of scientists in the us, Canada, Norway, the uk and Japan are working towards understanding gas hydrate and the role it plays in the global climate and the future of fuels. Besides, scientists at United States Geological Survey are also trying to solve the mystery of Bermuda Triangle, wherein loss of gas from underlying deposits of gas hydrate, are being considered responsible for the extensive ship-sinking incidences.

Related Content

- Financing coal phase-out: public development banks’ role in the early retirement of coal plants

- 2022 year in review: climate-driven global renewable energy potential resources and energy demand

- The evolution of energy efficiency policy to support clean energy transitions

- Clean electricity within a generation: Paris-aligned benchmarks for the power sector

- Carbon pricing and fossil fuel subsidy rationalization tool kit

- Oil 2023: analysis and forecast to 2028