Fish wars of an economic kind

IF YOU cannot agree to something right away, the UN has a simple solution: call a conference later. That is precisely what the Rio conference did on the vexatious question of straddling fish stocks. These are stocks of fish that migrate into one country's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from another's or between national EEZs and the open high seas. Over-fishing in the high seas by one nation can deplete the fish stocks within the EEZ of another.

IF YOU cannot agree to something right away, the UN has a simple solution: call a conference later. That is precisely what the Rio conference did on the vexatious question of straddling fish stocks. These are stocks of fish that migrate into one country's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from another's or between national EEZs and the open high seas. Over-fishing in the high seas by one nation can deplete the fish stocks within the EEZ of another.

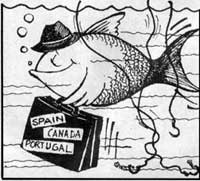

The issue of straddling fish stocks led to a clash between Canada, on one hand, and Japan and the European Community, on the other. Therefore, it was decided in Rio to hold an international conference on straddling fish stocks in Newfoundland in 1993 to work out regulatory measures for this legally curious national property which is also a global common property resource.

Canada, which put this issue into Agenda 21, had to fight a tough battle with Spain and Portugal, whom it accused of over-fishing outside its coastal waters. Canada was desperate to get this issue resolved because depletion of cod stocks along the Canadian coast has been so great that it has led to large-scale unemployment in its fishing industry.

While countries have their own regulations for controlling fishing within their respective EEZs, the zone beyond that is virtually nobody's area. Canada's proposal that the internal regulations of the coastal states should be extended beyond their EEZs was criticised by other fishing nations.

"If Canada's demand is conceded, then the entire ocean will get divided and dominated by coastal states. There will be no high sea left," reacted a delegate from Japan. "Canada is trying to bargain for a special interest outside its economic zone. If that happens, then coastal countries will claim special interest in every fish." Japan fears that such measures will help coastal states establish a hegemony on highly migratory stocks like tuna, which is totally unacceptable to it as tuna is its principal export.

Almost 40 countries, including the small island countries, supported Canada's move. But other countries like USA, Japan, and India opposed it. Said Camila Villarina Marxo of Spain, "About 95 per cent of the total catches along the Canadian coast are inside its EEZ. How can overfishing result from only 5 per cent of the total fish catch?"

The 11-member Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation supervises fish stocks in the north-west Atlantic, but the European Community started setting its own higher quotas in 1986 and its fishing fleets often exceeded even those. Canada wants international norms to be set on the basis of scientific and commercial data. "Under the present fishing regime, EC members have started controlling the quotas. Canada has massive problems on account of that," complained Louise Cote, a Canadian delegate to UNCED.

"Some countries are resisting the proposed conference because it would be binding. But I don't see why these countries need to worry so much. We want the membership of the conference to be based on a tradition of fishing." So now the next round of fish wars will be in Newfoundland!