Losing the edge

DESPITE India's centuries-old tradition of Ayurvedic medicine, the country is missing out entirely on the Western world's multi-billion-dollar drive for plant-derived drugs and "natural" cures.

DESPITE India's centuries-old tradition of Ayurvedic medicine, the country is missing out entirely on the Western world's multi-billion-dollar drive for plant-derived drugs and "natural" cures.

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, a survey in the US indicated a total market of some $13.7 billion (about Rs 42,500 crore) in 1990 for "unconventional therapy" (medical interventions not taught widely in US medical schools), with one in three Americans using at least one such remedy. Most therapies are for chronic diseases such as back problems, allergies, arthritis and insomnia. The survey also found unconventional therapies are generally used as adjuncts to conventional therapy.

Similar trends have been identified by market surveys in western Europe. A survey reported in the World Health Forum found traditional Chinese medicines are popular in Malaysia. They are used not because they are inexpensive, but because they fill gaps caused by the ineffectiveness or deficiencies of modern medicine.

In addition, Western pharmaceutical companies are increasingly reverting to investigating traditional plant cures as a short-cut to identifying active drug ingredients. This approach was used to identify substances that subsequently formed the basis of important and popular drugs. But it fell out of favour a few years ago because of expectations that new laboratory biotechnologies would be a faster route to drug development.

Looking for clues However, the laboratory and computer approach proved costlier and slower than expected. "We are still not at the point where we can routinely design drugs from first principles without any clues," says Lynn Caporale of the pharmaceutical giant, Merck.

So the pendulum has swung back and companies are prospecting the world's forests for medicinal plants. The US firm, Shaman Pharmaceuticals, which was set up only three years ago, researches plants if they are used in three communities for a similar purpose. The company has already patented drugs for influenza and herpes. Merck has tied up with a government-backed organisation in Costa Rica for the right to screen forest plants and develop active ingredients on payment of a royalty (Down To Earth, February 28, 1993). The US National Cancer Institute studies about 4,500 plants a year.

This is not shot-in-the-dark research, but hard-headed business practice based on previous commercial successes. The idea of using the cinchona tree bark as an anti-malarial drug -- which led to quinine --- was taken from indigenous communities in Latin America. The source of steroids used in birth control pills was the Mexican yam. The use of extracts of rosy periwinkle in the drug vincristine, used to treat certain childhood cancers, stemmed from traditional use of the shrub in Madagascar. About a quarter of all medical prescriptions in the US are derived from plant or microbe substances or from synthetics that copy such substances. An example of a drug developed from an Indian plant is the drug reserpine, which has a worldwide market of $42 million a year, according to the Brazilian Foundation for Medicinal Plants. The first clue about the drug came from Ayurveda, which recommends the use of sarpagandha (Rauwolfia serpentina), a wild herb, for hypertension, insomnia and insanity. Initial research on sarpagandha was carried out by R J Vakil, an Indian scientist in Bombay, and published in 1949. The Swiss company, Ciba Geigy, conducted further research and patented reserpine in the 1950s.

One of the complaints about such developments is that while companies rake in large profits, the people who discovered the medicinal properties of plants and kept the knowledge alive in their traditional medicine systems never receive any benefits. Some of the controversy surrounding the international convention on biological diversity negotiated at the Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro last year and the current negotiations on international trade stem directly from this issue.

However, even without the right to compensation, India can profit from its knowledge of medicinal properties of plants by developing Ayurvedic products and selling them abroad. All that is required is investment in research and development and commercial marketing expertise.

With this in mind, the government's Central Council of Ayurvedic Research (CCAR) arranged a conference of Ayurvedic vaidyas in 1961 to prepare a list of useful Ayurvedic plants. Three years later, a drug research scheme was launched by CCAR, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. The Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI) began screening Indian flora -- including marine plants -- and has covered 4,000 species so far. Despite these efforts, only two drugs -- guglip and peruvoside -- have reached the market and the latter, a tonic for heart patients, has not been a commercial success.

Guglip, used to control fat and cholesterol, was developed from the guggul plant, whose anti-inflammatory and anti-obesity properties were cited in Indian literature 2,600 years ago (Down To Earth, April 15, 1993). Investigation of its properties began in 1964 and was initially directed towards verifying references in the ancient texts. Chemical investigations were carried out by a team headed by Sukh Dev, first at the National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, and later at the Malti-Chem Research Centre in Vadodara. Biological work was carried out at CDRI. The research established both the anti-inflammatory and hypolipidaemic (cholesterol-reducing) properties of the resin.

The hypolipidaemic factor was converted into an Ayurvedic drug in which the active principal is administered as one of several ingredients instead of being extracted and used as a pure compound (a more expensive option).

CDRI says Guglip manufacturer Cipla Ltd now faces a shortage of raw material, a yellowish gum resin extracted from commiphora mukul, a small tree growing wild in the semi-arid regions of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Karnataka. It is only recently that cultivation of the tree was started. ICMR senior deputy director general G V Satyavati feels research might help increase yields, but such work should be undertaken by Cipla.

Cipla exports the drug to the US, which applies stringent conditions on drug imports. Despite entering the US market, the drug is not marketed in other countries because, a company official admits, of lack of marketing muscle.

Guglip is the only success story from three decades of government-backed research. Dev, now with the chemistry department of the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, calls this record "a rather dismal performance". Often, he says, Indian scientists rush to publish their research, which then becomes available to the world at large.

Commercial constraint

A major constraint in realising Ayurvedic medicine's potential is the CDRI's lack of commercial approach. "Often, commercial potential is not appreciated," says CDRI deputy director J S Tandon, who attributes the success of multinationals to the business environment in which their scientists work. Right from the establishment of a "lead" to the development of a marketable drug, a critical level of inputs in terms of finance, personnel and expertise is required. Potential drugs needs to be turned into a commercial product as quickly as possible because when a drug's limited patent life expires, other manufacturers can move in and cut into profits. "The kind of decision-making the situation demands is alien to bureaucratic processes," admits a CDRI scientist.

Many of his colleagues feel the lack of a commercial environment is partly behind the failure to capitalise on research in 1971 on extracts from the roots of Coleus forskohlii (Gujarati garmal). CDRI filed a patent application for the drug two years before Hoechst Pharmaceuticals of Bombay, but lost the race. The official explanation was there were errors in documentation submitted with the application. Although the product subsequently marketed by Hoechst, Forskolin, cannot be used as a medicine because it is non-soluble in water, it is an important laboratory chemical.

In addition to creating an "enterprise environment", there is need to acquire equipment that will enable the study of effects of plant extracts on diseases. This is much faster than feeding extracts to laboratory animals or clinical trials. Dev says, "It is absolutely essential that such facilities are set up as quickly as possible." Extracts are now being sent abroad for testing. He also points out that up-to-date equipment, costing about Rs 15 crore, would facilitate speedy evaluation of formulations used in India's traditional systems of medicine.

The C forskohlii case highlights another key issue: the wide gap between government research and commercial production, for which each side blames the other. V N Pandey, director of the Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS), complains industry takes virtually no interest in research; N S Bhatt, medical director of Zandu Pharmaceutical Works Ltd, complains industry is cold-shouldered when it approaches government bodies or academics.

An example is provided by ICMR's research and development of khsaara sootra (medicated thread) for the treatment of a fistula (an abnormal passage between a hollow organ and the body surface or between two hollow organs). It obviates the need for surgery, which is recommended in Western medicine. The benefits are a lower recurrence rate -- 4 per cent compared to 11 per cent in the case of surgery -- and no hospitalisation. However, treatment lasts upto 8 weeks (4 weeks in the case of surgery) and requires weekly visits to the doctor.

Making the thread is a complex process, which ICMR senior deputy director G V Satyavati feels is why industry has not taken much interest in it. The process involves coating a surgical thread of a specified thickness with fresh latex of Snuhi or Euphorbia neriifolia (a cactus), a specially prepared alkaline powder (khsaara) from the plant apaamarga (Achyranthes aspera) and dried turmeric powder. The thread is first given 11 coats of latex, followed by seven alternately applied coats of khsaara and latex. In the final phase, three coatings of latex and turmeric powder are applied alternatively. The 25-cm khsaara sootra is then sterilised and sealed in containers.

But marketing the thread has been held up because while ICMR feels industry should take it up, industry expects the research to be made available for commercial exploitation.

Similarly, Central Council for Research in Unani Medicine (CCRUM) claims to have developed a package for leucoderma patients. Its view is that the initiative now rests with individual companies. But the first inquiries have come from foreign firms.

Lack of inter-agency collaboration is also a problem. "Each of us holds on to a kingdom of research," admits Pandey. C H S Shastri, advisor, Ayurveda, in the ministry of health, is acutely aware of the difficulty and notes that many Ayurveda researchers reject a multi-disciplinary approach on the ground that research can be done only with Ayurvedic philosophy. Dev says that although a fair confirmation exists of what is said in India's ancient literature, the industry is nervous about systematic evaluation of their formulations.

The alternative to developing Ayurvedic and Unani products for export as medicines is to market them abroad as they are. If they are sold as "food supplements" or tonics, they are exempt from the tough licensing standards set by industrialised countries for "scientific" medicines.

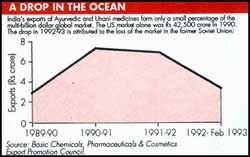

Exports of Ayurvedic and Unani products totalled Rs 6.91 crore during 1991-92 and Rs 3.42 crore during the first 11 months of 1992-93, according to the Basic Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals & Cosmetics Export Promotion Council (See table). Industry sources say the drop was due mainly to the loss of the Russian market.

The director general of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics puts the figure at Rs 27.59 crore in 1991-92, a discrepancy probably explained by different product definitions. Dabur India Ltd is the country's biggest manufacturer of Ayurvedic products, with a turnover of more than Rs 250 crore. It exports products such as chyavanprash, shilajeet and ashwagandha as well as cosmetics. Its 1992-93 exports are placed at Rs 15 crore, two-thirds of which were cosmetics. Says export manager Anil Gupta, "We concentrate on cosmetics, which have easy acceptance". The target buyers are overseas Indians.

Hamdard (WAKF) Laboratories has a turnover of about Rs 60 crore, but insignificant exports. Maharishi Ayurved Corp has been promoting panchkarma abroad. Sanjay Shrivastava, general manager, technical, says the company exports medicines worth Rs 15 crore a year. Inhibiting attitudes These are small amounts, given the potential size of markets. But manufacturers argue exports are inhibited by attitudes such as those expressed by J C Sobti, honorary general secretary of the Indian Medical Association, who feels Indian systems of medicine are nothing but quackery. M Sachdeva, secretary of the Medical Council of India, dislikes even the mention of "traditional systems of medicine". In the face of such stances and the fact that only 3 per cent of the health budget is spent on traditional medicine systems, Bhatt complains, "How can we market our traditional systems abroad when they are not respected in our own country?"

Such examples are not the whole story, because domestically, the makers of traditional medicines do not face price controls, unlike allopathic drug manufacturers, and are exempt from excise duty. Products can be marketed through any outlet and products mentioned in ancient literature don't require clinical trials.

However, several factors inhibit the development of an export market. One is the absence of drug standardisation. CCRAS and CCRUM have standardised formulation and processing methods, but this by itself only ensures that manufacturers have followed appropriate procedures.

Ayurveda's reputation has also been put at risk by unscrupulous companies. Paul Turner, professor in the department of clinical pharmacology of St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, recently claimed that testing of Indian traditional medicines has shown they contain unacceptable concentrations of heavy metals and are heavily contaminated with bacteria derived from human bowels.

There have also been cases of death and disability after consuming sub-standard products, like the incident in which 200 people died and hundreds of others were blinded after taking Kapoor Asav, an Ayurvedic medicine for diarrhoea and dysentery, in 1991.

Select, a drug marketed by Vasu Pharmaceuticals Pvt Ltd, Ahmedabad, claims to guarantee a male child to an expectant mother if it is taken 45 days after the last menstrual period.

Industry does not seem particularly worried by the possibility that such abuse and poor quality standards will tarnish the image of traditional systems of medicine. The issue is not being taken up at an industry-wide level.

Health ministry officials concede the Drug and Cosmetics Act is inadequate, that issuance of drug licences is a state subject and there is no penal provision in the case of wrongful issuance of licences. However, a committee has been set up to examine the issue of Ayurvedic drug manufacture and marketing and its report is expected by the end of the year.

But it will take major changes before India can contemplate cashing in on its Ayurvedic traditions, including a better working relationship on research between the various government agencies and between government, academic institutions and industry; extensive investment; entrepreneurial decision-making, and an understanding of foreign markets.

Related Content

- Paris environment pact closer to coming into force

- Miners lose edge as NSW government balances profits against damage before approvals

- Miners lose edge as NSW government balances profits against damage before approvals

- Ominous sea pushes coastal villagers to the edge

- Mosquitoes score in chemical war

- India loses competitive edge due to poor health, infra