Kala azar: inheritance of the meek

In a degraded environment rife with germs of disease, the poor are always the hardest hit, and kala-azar is no exception. Satnarayan Chaudhary of village Khakharwa of district Begusarai waits outside the Kala-azar Research Centre in Patna, along with his wife who has kala-azar. Before coming to the state capital, he has already spent about Rs 5,000 on her treatment. He has just sold his calf for Rs 1,200 to reach Patna . "I am left with only Rs 300. I will have to either borrow money or sell my land for my wife's treatment,' he laments. V P Sharma, former director of the Malaria Research Centre, Delhi, points out that the first line of treatment costs Rs 800-1,250, and the expenses rise with the second line of treatment as the drugs are imported. At the same time, the cost of treating the relapse situation (post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis) can be as much as Rs 15,000.

In a degraded environment rife with germs of disease, the poor are always the hardest hit, and kala-azar is no exception. Satnarayan Chaudhary of village Khakharwa of district Begusarai waits outside the Kala-azar Research Centre in Patna, along with his wife who has kala-azar. Before coming to the state capital, he has already spent about Rs 5,000 on her treatment. He has just sold his calf for Rs 1,200 to reach Patna . "I am left with only Rs 300. I will have to either borrow money or sell my land for my wife's treatment,' he laments. V P Sharma, former director of the Malaria Research Centre, Delhi, points out that the first line of treatment costs Rs 800-1,250, and the expenses rise with the second line of treatment as the drugs are imported. At the same time, the cost of treating the relapse situation (post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis) can be as much as Rs 15,000.

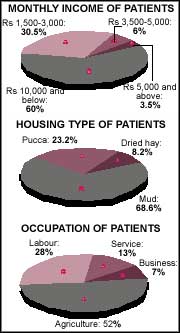

In the 1991-92 epidemic, all the households in Chakjamal village of Vaishali district in Bihar were afflicted by kala-azar. The burden of disease is obviously immense, especially for low-income rural households. Socio-economics play an important role in the battle against kala-azar. A 1997 study conducted by the Balaji Utthan Sansthan in Patna showed that poor people are the worst affected by kala-azar: 60 per cent of patients had a monthly income of less than Rs 1,000, whereas only 3.5 per cent had a monthly income more than Rs 5000.

A family's financial situation influences the type of house they can afford and the type of work they do. Analysis of the housing conditions of kala-azar victims revealed that 68 per cent lived in mud houses, which favour the growth of sandflies as the cracks and crevices of mud houses provide habitat for the insect. Furthermore, it was found that 52 per cent of patients were agriculturalists and 28 per cent were labourers.