Mughal system stilll supplies water at zero cost

THE OLD water works of Burhanpur town is an impressive example of Mughal engineering skills. Named for Sheikh Burhanuddin, the town was built in 1400 on the banks of the Tapti in Khandwa district of Madhya Pradesh. The founder, Nasir Khan Faruqi, established it as the capital of the Faruqi dynasty of Khandesh, which existed for two centuries until its annexation by Akbar in 1600. Burhanpur steadily grew in importance because it was considered the gateway to south India. Heirs to the Mughal throne were posted at Burhanpur, described in the Ain-i-Akbari, the chronicle of the rule of Akbar, as a city of gardens, some of which boasted of sandalwood trees. Burhanpur was famed for its fine cloth, gold wire drawing and other allied crafts and industries. Burhanpur is also remembered as the city in which the Empress Mumtaz Mahal died and where her body was kept until Emperor Shah Jahan could build the Taj Mahal in which is buried.

THE OLD water works of Burhanpur town is an impressive example of Mughal engineering skills. Named for Sheikh Burhanuddin, the town was built in 1400 on the banks of the Tapti in Khandwa district of Madhya Pradesh. The founder, Nasir Khan Faruqi, established it as the capital of the Faruqi dynasty of Khandesh, which existed for two centuries until its annexation by Akbar in 1600. Burhanpur steadily grew in importance because it was considered the gateway to south India. Heirs to the Mughal throne were posted at Burhanpur, described in the Ain-i-Akbari, the chronicle of the rule of Akbar, as a city of gardens, some of which boasted of sandalwood trees. Burhanpur was famed for its fine cloth, gold wire drawing and other allied crafts and industries. Burhanpur is also remembered as the city in which the Empress Mumtaz Mahal died and where her body was kept until Emperor Shah Jahan could build the Taj Mahal in which is buried.

Because Burhanpur was an active trade centre and the boundary of the Mughal empire, an army of two lakhs was posted there at a time when the town's civic population was about 35,000. The town's ingenious waterworks was to provide this population with fresh water. One might wonder, though, why would a town that is situated on the banks of the Tapti, a perennial river, need such an elaborate and protected water supply system? The answer is that the Tapti flowed through other kingdoms, too, and due frequent battles with the Mughals, there was always the possibility that the Tapti could be poisoned if a war broke out, and so depending solely on Tapti water could be suicidal. This led to Abdul Rahim Khan conceiving of a groundwater based scheme and in 1615, a Persian geologist, Tabkutul Arz, investigated the recharge valley in the Tapti plains between the Satpura ranges. he then devised underground tunnels and infiltration galleries to supply the town with water.

Eight waterworks systems were constructed and these have at different times supplied water to the town. Two of the waterworks systems were destroyed a long time ago, but the other six still exist. Three of them continue to supply water to Burhanpur and the other three supply water to Bahadurpur, a nearby village, and Rao Ratan Mahal.

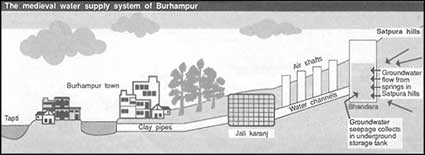

The Burhanpur water-supply scheme consists basically of bhandaras (storage tanks) that collect the groundwater from underground springs flowing from the Satpura hills towards the Tapti. The groundwater is intercepted at four points that are located to the northwest of Burhanpur town -- Mulbhandara, Sukhabhandara, Khunibhandara and Chintaharan. The water is then carried by subterranean conduits linking a number of connected wells to a collection chamber called Jali Karanj and from there to the town.

The waters from the Mulbhandara and Chintaharan meet at one point and is then carried to the Khunibhandara and on to Jali Karanj. Water from the Sukhabhandara runs into the water coming from Khunibhandara at a point little before the Jali Karanj. During Mughal times, water from Jali Karanj was piped to Burhanpur town through clay pipes. The British replaced the clay pipes of the Mughal era with iron pipes. Unlined tunnels connecting the shafts convey water from the source to the town. The tunnels are about 80 cm wide and about 200 m long with air shafts every 20 m along their entire length from the bhandaras to Jali Karanj. Today, people living near these air shafts use them as wells throughout the year.

The entire water-supply system is based on gravity and the underground tunnels have a suitable gradient. Water from the Sukhabhandara, a tank nearly 30 m below ground level, flows into the tunnel. The depth of the water in Sukhabhandara, even in the summer, is about 1.5 m. Masonry walls of about 100 cm thickness give support to its natural rocky base and openings are provided to allow groundwater to percolate into the bhandara. The Mulbhandara, situated 10 km from Burhanpur on the bank of a stream, is an open tank made of stone masonry 15 m below ground level and surrounded by a wall 10 m tall. Chintaharan is located close to the Mulbhandara and ata depth of about 20 m. The Khunibhandara, located about 5 km away from Burhanpur, receives water by gravity from Mulbhandara and Chintaharan and collects it at a depth of about 10 m. The bottom of the bhandara is made of stone masonry and there is a brick wall around it. Jali Karanj is where water from the other four bhandaras meet about 2 m below the ground and is then supplied to the town. However, with the Burhanpur Tapti Mill discharging bleaching and dyeing effluents near Jali Karanj, the entire system is now threatened by pollution.

Burhanpur's present population is about 1.85 lakh and the total water supply to the towm is about 90 lakh litres per day - - 76.5 lakh litres from dugwells and borewells and 13.5 lakh litres from the old waterworks, which even after 350 years works at zero cost. According to G S Patil, an assitant engineer for Burhanpur municipal corporation, the Mughal built water-works can supply upto 18 lakh litres daily. Thus, there is underutilisation of the ancient water-supply system. In the past few years, the local municipal corporation has begun realising the system.

Over the years, the main problem with the Mughal system has been a diminishing supply of water. During the Mughal period, this supply amounted to about 100 lakh litres of water daily. Today, the maximum output possible is 30 lakh litres. Furthermore, the percentage of magnesium and calcium in the water is high. Over the years, the system's pores and openings became choked because of the accumulation of these chemicals on the walls of the tunnels, shafts and bhandaras. The incrustation in some places is as thick as 15 cm. As these deposits have been growing in over the centuries, there has been a drop in the rate of infiltration of groundwater into the galleries and this has reduced the the total yield. Another reason for the reduced yield is that innumerable tubewells have been dug in the past few years for farming and as more and more water is pumped out, the groundwater level has also fallen, resulting in a reduction of the groundwater percolating into the bhandars.

Due to overexploitation of the groundwater, many underground springs have dried up and with the coming up of the paper factory at Nepanagar and also because of growing population pressures, the forests have slowly disappeared. With no tree cover, the rainwater flows into the Tapti, instead of recharging the groundwater. A problem that has risen recently is degraded water quality. Alkaline dust from Rai Lime Mill falls into the shaft from the open kundies and contaminates the water. Since slums have sprung up around the kundies, people bathe and wash clothes on the platforms near the kundies and waste water seeps into the shafts.

Also, two kundies near the railway station were broken at the top and rainwater and sewage from the surrounding locality are entering the tunnel and contaminating the supply. All this indicates that the end of an extraordinary water-supply system is immminent, unless repairs and other corrective measures are undertaken.