Real remedy

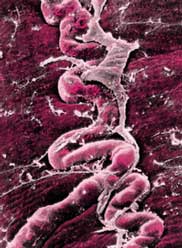

IN MAKING blood vessels, or for that matter, that remarkable pump that unfailingly works, nature has no match. But scientists from Organogenesis, a biotech company in Canton, Massachusetts, USA, say they have come close by drawing on natural ingredients. Using pig intestines, a cow protein and the blood-thinning agent heparin, Susan Sullivan and her team produced artificial vessels that soon started acting like real ones and served rabbits well for a record 90 days.

IN MAKING blood vessels, or for that matter, that remarkable pump that unfailingly works, nature has no match. But scientists from Organogenesis, a biotech company in Canton, Massachusetts, USA, say they have come close by drawing on natural ingredients. Using pig intestines, a cow protein and the blood-thinning agent heparin, Susan Sullivan and her team produced artificial vessels that soon started acting like real ones and served rabbits well for a record 90 days.

This new method of constructing artificial blood vessels that in animal experiments eventually become indistinguishable from normal vessels may prove useful in coronary bypass patients who are unable to donate their own blood vessels. "The initial response to this graft is really promising," said Sullivan, senior research director at the company. The researchers say the finding could lead to new replacement arteries for people, if trials in larger animals show equal promise (Nature Biotechnology, Vol 17, No 11).

For many years, researchers have tried many ways to produce artificial blood vessels but such attempts have largely been unsuccessful. Tubes made from synthetic materials such as plastics easily clog up, while those from animal tissue or proteins tend to spur immune rejection or inflammation in humans. Scientists have also tried producing vessels from a patient's own cells, but that has proven technically difficult and very time consuming. These synthetic products did not allow cells to move into the vessels and remodel them. The use of collagen, a connective protein, changed it all.

"Collagen is different because it's a natural substance. Cells are used to seeing it," Sullivan said. Therefore, the body's cells work with the graft to integrate it into the existing vascular network. In addition, previous synthetic blood vessels had to be larger than five millimetres in diameter and placed in an area of high blood flow, or else they would clog or clot. However, whether the same response will be seen in humans is still not clear as Sullivan and her colleagues studied only healthy, young adult rabbits. "You would expect that the responses would be different from what you would see in a 70-year-old bypass patient with cardiovascular disease," she said.

Related Content

- Judgment of the Supreme Court regarding district survey report for environmental clearance, 08/05/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding the issue of encroachment and pollution being faced by lakes and water bodies of Terai region, Uttar Pradesh, 11/03/2024

- Plastics: the cost to society, environment and the economy

- Written submission by Bhavaani Nadhineer Matrum Nilaththadi Neer on the report submitted by the Joint Committee on river Bhavani, 05/07/2021

- CPCB report on steps to contain air pollution in India, 06/03/2020

- India State of Forest Report 2017