Jaisalmer`s architectural wonders beat the heat

Jaisalmer fort and the rest of the of the city was built for heat, with wind corridors and the architecture providing built-in comfort for its denizens. Jaisalmer is not unique. Cherrapunji, the wettest town on the planet, is also built to cope, as Down To Earth will report in the next issue. On a trip to Rajasthan archi rastogi finds how Jaisalmer built itself to be a cool place

Jaisalmer fort and the rest of the of the city was built for heat, with wind corridors and the architecture providing built-in comfort for its denizens. Jaisalmer is not unique. Cherrapunji, the wettest town on the planet, is also built to cope, as Down To Earth will report in the next issue. On a trip to Rajasthan archi rastogi finds how Jaisalmer built itself to be a cool place

There is a popular saying in Rajasthan: ghoda kije kaath ka, pind kije pasaan, baktar kije lohe ka, phir dekho Jaisan. Loosely translated it means: turn your horse to wood, make your body rock-like, wear clothes that are like iron, then come and see Jaisalmer.

It's a precept which cannot be taken lightly. Certainly not, with the media reporting temperatures around 50 degrees c. But there is something about Jaisalmer that quickly puts one at ease. The city is hot all right.But there is a pleasant incongruity between the barometer and Jaisalmers ambience. The key lies in how this city in Rajasthan was built.

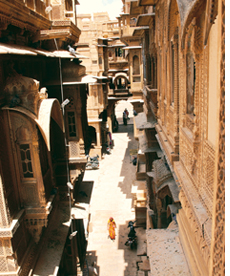

Jaisalmer fort stands atop a hillock overlooking a township where colourful medieval architecture exists cheek-by-jowl with nondescript small town dwellings. From a tall building nearby, the fort seems like a sand castle, standing atop a dune. One may wonder if it will survive a strong shower. But Navneet Vyas, a local historian, brushes off the doubts. He says the sand is very strong and the fort and its adjoining areas have been planned to keep the weather on hold.

The fort, in fact, has been described as an architectural marvel by experts. Most of its gates face the northeast and the western parts are higher and thicker, helping the wind get in. Balconies from the havelis inside jut out into the streets, inviting the breeze. The wooden ceilings of these buildings are overlaid by a local material called muram, says Prahlad Singh Bhati, an expert on the traditional structures in the Thar desert at the School of Desert Sciences, Jodhpur. Bhati adds that muram is adept at deflecting heat away from the buildings. Made from limestone, it also checks water seepage.

Today much of the fort is the centrepiece of a bustling tourist market, with many havelis inside having been converted into hotels. Captain Chandra, owner of one such hotel, has installed air conditioners in the best suites, but comfort levels here still have a lot to do with traditional wind management.

Parallel rows of windows line walls in the rooms, making them airy and well-ventilated. An ensemble of a rug, a ceiling fan, a mosquito net and some traditional ware make up a suite, making it possible for scores of tourists to afford a stay at the fort. The rooms are very cheap at this time of the year.

It's getting hotter in Jaisalmer, media reports say. Many like Kushala Ram blame the weather on the nuclear tests that were conducted in nearby Pokhran.

But queries about climate change only elicit a dismissive nod from a group of youngsters. "It's the same every year. Every summer, or winter, people complain of extreme weather. But nothing has actually changed," says Kamal Kishore.

But queries about climate change only elicit a dismissive nod from a group of youngsters. "It's the same every year. Every summer, or winter, people complain of extreme weather. But nothing has actually changed," says Kamal Kishore.

It's a view that 50-year old Din Dayal Chhangani, doesnt approve of. Dayal, who runs a restaurant and a stationery shop near the fort, says, "The climate has become worse in the last two years." He rues that there has been no storm for the last few days. "Though the roads would be blocked with sand, it will at least get cooler," he says.

Dayal's family has braced itself for the summer. Their house has an air cooler and the water tank is filled to its brim. "We take precautions against summer diseases like diarrhoea. Much emphasis is given to eating right. Only local people can withstand this heat," he says.

Experts too talk of the rising mercury. Anil K Chhangani of jnv University, Jodhpur, for example, says, "There has been an increase of up to 2 to 2.5 degrees in the day temperatures over the past 10 years." He attributes this to increasing mining and logging.

Anil K Chhangani of jnv University, Jodhpur, for example, says, "There has been an increase of up to 2 to 2.5 degrees in the day temperatures over the past 10 years." He attributes this to increasing mining and logging.

Curvy streets

As the sun blazes at its fieriest in the afternoon, Dayal pulls down his shops shutters and heads home. So do most other shopkeepers. The town slows down with few daring to brave the sun. Down To Earth spots a group clearly relieved after catching their breath near the hawa prol, the wind gate of the fort. The wind is strong in the narrow and curvy streets of the fort as it is outside.

Historians say the convoluted nature of the streets was a deliberate ploy in medieval times to confuse attacking armies.

But experts also say the winding streets help deflect the sun and encourage the southwesterly wind. "As the principle goes, fluid velocity increases when the volume decreases. The turns and tunnels in the streets make the wind stronger," says Vyas.

Trouble ahead

The fort was created to accommodate a few hundreds of people. But the new tourist influx has created problems. Nand Kishore Sharma, a historian and the director of a museum, the Jaisalmer Lok Sanskratik Sangrhalaya, says that water has started leaking into the foundations of the mediaeval structure and is creating serious problems.

Sharma says tourism has ruined the fort. The drains in the Jain temples were designed for sustainable use. Water from the sanctum sanctorum drains into a tank for further use; there are bathtubs of stone, where the bath water is retained and then used for washing, and still later used for animals or even to make gaara. But today, the wells do not have enough water, which now comes in erratic supply from outside.

Though developed centuries ago, Jaisalmer's sophisticated constructions concur with modern science, says S M Mohnot of the School of Desert Sciences, adding there have been few innovations made in it. "The same resource is being used in the same way even after centuries."

Though developed centuries ago, Jaisalmer's sophisticated constructions concur with modern science, says S M Mohnot of the School of Desert Sciences, adding there have been few innovations made in it. "The same resource is being used in the same way even after centuries."

Kashim, a resident of Chhatrail village about 15 km away, says the trend of pukka houses is increasing today; this is affecting the atmosphere and shooting the temperature up. With growing security concerns, also arise many urban aspirations, he says.