Little brother`s tale

COG and Kismet are "brothers". They might not share the same blood, but they definitely share a microchip or two. Their parents, several scientists wracking their brains to come up with intelligent, artificial life forms, are trying to "teach" this robotic duo a thing or two about the world they "live" in.

COG and Kismet are "brothers". They might not share the same blood, but they definitely share a microchip or two. Their parents, several scientists wracking their brains to come up with intelligent, artificial life forms, are trying to "teach" this robotic duo a thing or two about the world they "live" in.

Scene: the artificial intelligence (AI) department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT), USA. A disembodied head with gremlin-tike features is about to be given that precious gift - the gift of life. And Kismet, a robot-head that learns about its environment like human baby, is all set to wake up.

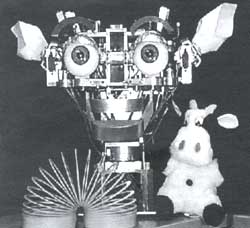

Researchers working on Kismet are part of a larger group in the AI department that is building an artificial humanoid, fondly called Cog. Kismet, Cog's baby brother, has a 3.6-kg head capable of displaying a wide range of emotions. To do this, Kismet has been given movable facial features that can express basic emotional states that resemble those of a human infant.

Kismet can thus let its "parents" know whether it needs more or less stimulation - an interactive process that the researchers hope will produce an intelligent robot that has some basic "understanding" of the world.

This approach of creating AI by building on basic behaviours contrasts with older methods which involved cramming a computer with lots of facts in the hope that intelligence will eventually emerge.

Cynthia Breazeal, Kismet's creator, is giving it the same senses as a baby. So far it has only a basic vision system, but Breazeal is developing ways to make Kismet hear and even babble like a baby. Its eyes are made of charge-coupted device colour cameras that focus best at a distance of 0.6 metres - a visual acuity similar to a human infant.

Kismet also has a repertoire of responses driven by emotional and behavioural systems. The hope is that Kismet will be able to build upon these basic responses after it is switched on or "born", learn all about the world and become intelligent.

Crucial to its drives are the behaviours that Kismet uses to keep its emotional balance. For example, when there are no visual cues to stimulate it, such as a face or a toy, it will become increasingly sad and lonely and will look for people to play with.

Responding to Kismet restores its equilibrium, making it happy again. Similarly, if its carer endlessly repeats the same cue, such as shaking a doll in front of it, it will get bored and agitated. And if Kismet becomes overwhelmed with information, it is likely to tire and fall "asleep".

These responses are crucial to the project. Social interaction is always a two-way process: Kismet must be able to show its parents how it feels, so they can respond correctly. The robotic face sports ears, eyebrows, eyelids and a mouth that can move to form baby-like facial expressions such as surprise, fear, interest and so on.

Any advances made with Kismet will be passed on to its big brother Cog, the robot brainchild of Rodney Brooks, head of MIT's AI department. Cog is two metres tall, complete with arms, hands and all three senses - including touch-sensitive skin. Its makers will eventually try to use the same sort of social interaction as Kismet to help Cog develop intelligence equivalent to that of a two-year-old child.

Kismet is still very much in development, with Breazeal still tuning its emotive responses and working on its sensory apparatus. But she expects learning to start within a year. Will it work? "No one knows what the answer is since no one has done it yet," she says. "The only existing proofs of intelligence are the humans and the animals. So the case for embodiment is that if we do it right it will probably lead us where we want"

Meanwhile, Cog is getting close to completion. Brooks says all its components will be integrated over the next few months and once they are, he thinks that it can be considered to be an artificial life form.