Protect the tuskers damn the carvers

The Delhi high court has rejected a petition asking for the ban on ivory trade to be lifted. With this order there is now a total ban on selling and carving in ivory and all stocks of the precious 'white gold' can be confiscated.

The Delhi high court has rejected a petition asking for the ban on ivory trade to be lifted. With this order there is now a total ban on selling and carving in ivory and all stocks of the precious 'white gold' can be confiscated.

The petition was filed by the Ivory Traders and Manufacturing Association against the government notification to use up excess stocks of ivory by April 2, 1992. Though trade in Indian ivory was banned in 1986, traders could use African ivory with a licence and could import ivory under Open General Licence. But with trade in ivory being banned worldwide, the government moved fast to push the same in India.

The petition filed by the traders' association had allowed them temporary relief until July 7, 1992 to sell all stocks. They have claimed that the ban will force them out of business, and render jobless almost 20,000 artisans specialising in ivory-carving.

However, in its reply, the government dismissed the charge of growing unemployment of ivory craftspersons as a "figment of the petitioners' imagination". Government statistics show that the number of artisans in 1978 was 7,200 which had gone down to 2,000 by 1989 and today there are less than 1,000 ivory carvers. Most of these, too, had switched to sandalwood and camel-bone carving.

But a visit to the Jama Masjid area -- home to most Delhi-based carvers - belied this assertion. In the side lanes of Sita Ram Bazaar, behind the Jama Masjid in the walled city, Sunderlal Sharma reminisces about his father Bhagat Bhimsen, an ivory craftsperson. "My father received the National Award in 1966 for his craftspersonship. He was one of many mastercraftspersons whose work was recognised by the government. Now, the government is no longer interested in us and ivory craftspersonship is no longer valued," says Sharma.

Many see no future in the profession. But for those who have taken up other trades, the switch has not been easy or profitable. Babu Ram, who was trained by mastercraftsperson Chander Bhan Gupta, has given up his trade and now works in his father's tailor shop. He says, "I did not want to give up my trade, but there is no work. At least here, I can be of some use to my father." Others have taken up jobs in neighbouring shops or even started their own grocery shops. Most craftspeople have opted to carve in camel and buffalo bone or sandalwood instead.

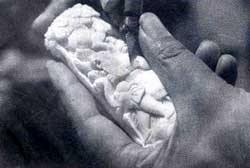

But they are far from satisfied. Firstly, these are poor substitutes for ivory. Gupta explains: "Bone is much more brittle and does not allow for fine craftsmanship. Carvings are much more simple and much of the skill of ivory carving is missing. A lot of the jali work, which characterised it, is no longer there. The intricate bead work has also gone."

Financial pressure is also beginning to tell. Prior to the ban on ivory, the demand for ivory handicrafts was great and therefore, also the demand for skilled artisans. Gupta estimates that his monthly income was anywhere between Rs 3,000 and Rs 4,000 per month. Now the story is different. The value of bone is next to nothing and its artistic value is not comparable to ivory. The small bone carvings he makes are sold for prices as little as one-third of their ivory equivalents.

The government has put the issue of ivory craftsmen on the backburner. While it was the ministry of environment and forests that decided upon the ban, when it comes to the issue of the craftspeople, their attitude has been "this has nothing to do with us, contact the textiles ministry." According to A K Hadoo, deputy director of exports at the office of the development commissioner of handicrafts, ministry of textiles, "Ivory craftsmen have been told to diversify into other crafts. As ivory craftsmen, they have the skills to adapt, so it is up to them to make the shift."

The government also claims that the objective of the ban on imported ivory is to protect the Indian elephant. The number of tuskers killed by poachers has risen from 42 in the mid-1980s to 121 in 1989, as it is difficult to differentiate between Indian and African ivory.

Perhaps such an approach should be looked at more closely before punishing craftspeople who are far from being responsible for the decline of the elephant population. As Sunderlal Sharma said: "We are not the ones responsible for the decline of the elephant population. So why are we stuck with the consequences?"