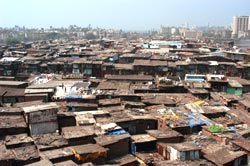

Slum today, gone tomorrow

if the Union cabinet endorses a recent decision of the group of ministers, about 35,000 shanties will have to be removed from Mumbai's Santa Cruz area and relocated on reclaimed saltpan land in Kanjur village on the outskirts of the city. The project is being showcased as the country's largest resettlement venture for such dwellings. But it has also rekindled the debate on the urgent need for a structurally sound national slum policy.

if the Union cabinet endorses a recent decision of the group of ministers, about 35,000 shanties will have to be removed from Mumbai's Santa Cruz area and relocated on reclaimed saltpan land in Kanjur village on the outskirts of the city. The project is being showcased as the country's largest resettlement venture for such dwellings. But it has also rekindled the debate on the urgent need for a structurally sound national slum policy.

"The government's proposal is devoid of logic because saltpan land comprises ecologically fragile tracts. It is the buffer that protects inhabited areas from the impact of the sea,' contends G R Vora, a Mumbai-based environmentalist. "In any case, most of this land falls under the Coastal Regulation Zone, which means it's a no-development belt,' he adds. An alternative site in central Mumbai, from where textile mills were shifted out, would have proved ideal for the purpose, asserts Vora. But he alleges that that land has been given to private builders for constructing shopping malls.

The Maharashtra government refutes the charges. "Huge strips of government-owned saltpan land are available where these slums can be easily relocated. We plan to build low-income houses on a large scale, and doing so on private land is not economical,' claims a senior official of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (mmrda), adding: "Rehabilitation has to be smooth.'

Experts feel that the authorities' arguments smack of arbitrariness. They ascribe this to the absence of clear-cut guidelines on slum development. "The draft national slum policy (dnsp) was circulated for public comments in 1999. While the document has undergone numerous revisions since then, its present status is not known. A delayed policy is no policy,' points out Sheela Patel, director, Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (sparc), a Mumbai-based non-governmental organisation.

The blueprint The dnsp is being finalised under the aegis of the Union ministry of urban development and poverty alleviation (moudpa). The policy formulation process began in 1997. It is premised on three primary objectives:

• To bring about the integration of slum settlements and communities residing within them into the urban area as a whole

• To strengthen the legal and policy framework for facilitating slum development and ensuring improvement on a sustainable basis

• To establish a process that would enable involvement of all stakeholders for the efficient implementation of policy objectives.

The draft policy also comprises nine governing principles and a number of essential strategic interventions. While the thrust was on clearing out and relocating slums earlier, the current approach is to look upon slums as an integral part of cities that contributes towards the economy. In effect, dnsp favours an upgrade for all such dwellings.

This implies providing basic amenities and improving infrastructure in existing slums. The policy delves into issues such as granting land tenure, rehabilitation, land-use plans, environmental improvement and social services.

Cracks in the brickwork dnsp's newfound focus on in-situ development of slums has evoked a mixed reaction. "There is no single solution to the problem of slums. But high-density, low-rise upgrading without moving people is a good option unless the dwellings are located in a dangerous place,' says Patel. At the same time, the definition of dangerous in this context is questionable. "According to dnsp, a site shall not be declared untenable unless existence of human habitation on it entails undue risk to the health or life of residents,' points out urban planner Gita Dewan Verma. "The policy leaves the decision of