Many faced workers

ROBOTS do their specific tasks quite well, but they are no good when confronted the new tasks. Similarly, they find it with difficult to deal with changes in terrain or working conditions. Engineers all around the world find it easier to design one robot for one job (Spectrum, No 256, 1997).

ROBOTS do their specific tasks quite well, but they are no good when confronted the new tasks. Similarly, they find it with difficult to deal with changes in terrain or working conditions. Engineers all around the world find it easier to design one robot for one job (Spectrum, No 256, 1997).

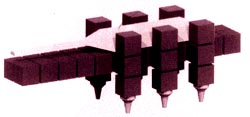

Now, British inventor Joe Michael, who works as a computer programmer with Robodyne Cybernetics in London has come up with a simple concept called the shape changing robot that could be the key to robots that could build cars, explore Mars or even build bridges. His idea is that instead of robots being of a specific size and shape and meant to do a particular job, they should consist of many, smaller identical cubical components. Each cube is equipped with motors, locking devices on surfaces and enough electronic processing power to attach to its neighbour when required, or to move along the neighbour's face. "A robot built of enough of these cubes could tackle almost any task," he explains.

Each cube also contains information processing circuitry, storing its unique :ddress' and is able to move relative to its neighbours according to instructions from a 'master cube'. Although some cubes might need specialist parts, for example, a waterproof face - each would be essentially identical and redundant if it fails.

When a rigid structure is needed, the cubes could fasten themselves firmly to their neighbours with retractable wedges. All faces of the cubes have four wedges. A system of gears allows each cube to slide along the face of its neighbour when two of the wedges are retracted.

If a walking machine is built from these cubes, it might have six pairs of legs arranged along its body. To move forward, the cubes comprising the front pair of legs would slide upward to clear the ground, then forward along the body and then down again. The rear two pairs repeat the process and finally the body itself slides forward. Each cube must be able to receive power from any of its faces and direct it to any other. One cube acts as a master computer, holding and issuing control messages to robotic cubes.

"Apart from the master cube," says Michael, "each building block would need only a modest computer on board - a microcontroller with about the same complexity as a watch or a calculator chip. The basic cube structure could be varied in many different ways. Some cubes might have 'fractal' faces, each capable of accommodating four smaller cubes. These in turn would be able to fit four more smaller cubes on each face, and then four more down to the limits of nanotechnology. Such a robot could carry out highly precise tasks."

The design concept has already won a lot of international awards at inventors' competitions around the world. The next stage is to build a working prototype. The challenge has been taken up by a team at the Open University, Britain's pioneering broadcast-based institute of further education.

Michael, in the meantime, is brimming with ideas for the invention. He envisages robots built from cubes between one and three centimetres in size. "Production lines built out of such components could be self-repairing," he says. Another idea is to build giant structures from the basic frames, filling the cubes with ice when in place. Such structures could quickly create dams, warehouses and bridges for military purposes or deal with natural disasters.

Related Content

- Decentralised renewable energy for agriculture in Malawi

- South Asia development update October 2023: toward faster, cleaner growth

- World development report 2023: migrants, refugees and societies

- Understanding enablers and barriers to social protection of sanitation workers

- Negotiations by workers in the informal economy

- South Asia economic focus: coping with shocks- migration and the road to resilience