Retrograde

state governments and non-governmental organisations (ngos) have sharply criticised the draft new environmental clearance procedures for certain kinds of projects released recently by the Union ministry of environment and forests (moef). While many states believe the proposed procedures go against the spirit of decentralisation, the ngo sector dismisses the changes suggested as too mild to adequately address environmental and social concerns.

state governments and non-governmental organisations (ngos) have sharply criticised the draft new environmental clearance procedures for certain kinds of projects released recently by the Union ministry of environment and forests (moef). While many states believe the proposed procedures go against the spirit of decentralisation, the ngo sector dismisses the changes suggested as too mild to adequately address environmental and social concerns.

The draft groups all activities needing environmental clearance in two categories: a and a/b. Category a contains 19 entries including river valley projects, industrial estates/parks, special economic zones, nuclear power projects, pesticides, pulp and paper industry and mining of major minerals. moef will clear all Category a projects.

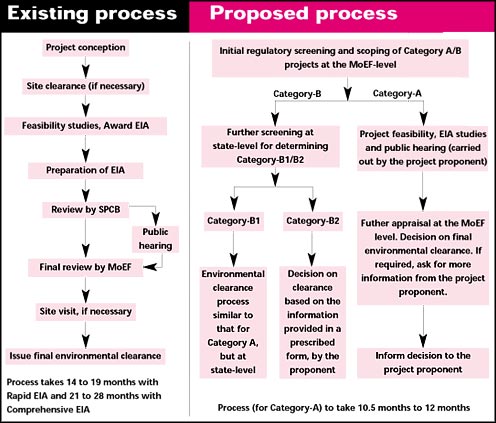

Category a/b lists 27 activities including cement (more than 200 tonnes daily production capacity), dyes, mining of major minerals over 5 to 25 hectares, oil and gas exploration, and railways, including metro rail. A screening and scoping expert committee (ssec) of moef will examine all such projects too on the basis of information provided by the project proponent. It will then decide whether the project falls under Category a or Category b. The state governments will clear all projects falling in Category b (see flow chart).

Explaining the classification, the draft says, "Proposals which are likely to have a higher impact on the environment or have impact on more than one state or a neighbouring country will fall under Category a requiring environmental clearance from the government of India.' A representative of the state government concerned will be associated with the ssec while screening a proposal, it adds.

Several states strongly oppose this. "A state government should have more say in clearing the projects. The Union government can play an advisory role,' asserts R Vaithilingam, minister for forests and environment, Tamil Nadu. Asim Burman, environment secretary of West Bengal, agrees: "The ssec should be at the state-level. Let the Union government appoint experts on the ssec and decide on a protocol to monitor clearances. But the final clearance should come from the respective state government.'

The draft has been prepared by a consultant as part of moef's Environmental Capacity Building Project, funded by the World Bank.

Ministers and secretaries from Tripura, Gujarat, Punjab, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim and Jharkhand were also apprehensive of the new proposals. "We are willing to listen and engage with the state governments to sort out any problems they have with the proposal,' says Meena Gupta, additional secretary, moef, adding, "One of our objectives is to reduce the number of projects coming for clearance to the Union government.' Ironically, the proposal has its genesis in several chief ministers' opposition to existing regulations.

Environmentalists see the new proposals leading to a power struggle. "The Union and state governments are wrangling over gaining the final authority to clear projects. None of them is interested in the actual process, or in adequately addressing environmental and social concerns,' says Sreedhar R of Academy for Mountain Environics, an ngo in Uttaranchal. Some activists fear the dilution of the laws. "As it is, the system is weak. The new proposals will further weaken the process,' says Leo Saldanha of Environment Support Group, a Bangalore-based ngo.

Public hearing The most contentious are the changes recommended in the public hearing procedures. The practice was started in 1997 to address the concerns of the affected people. The provision was added to the 1994 Environment Impact Assessment (eia) notification through an amendment. This was a welcome step because there have been instances of projects being cleared despite erroneous and incomplete eia documents (see box: Is this the norm?). But public hearings haven't been very effective either; sometimes projects have been cleared despite vehement protests from local people or environmentalists.

Conventionally, the respective state pollution control board (spcb) calls and conducts the public hearing, then prepares a report and sends it to moef, along with a no-objection certificate or a rejection, as the case may be. moef has the final say on the project. But now, the draft recommends that the project proponent call for and conduct the public hearing. The proponent may also select the chairperson for the hearing from among the names suggested by moef. This will make public hearings meaningless, says Sreedhar.

The reason for the change, moef says, is that the spcbs take up to six months to conduct a hearing, thus delaying the process. To remedy this, argues Burman, moef can stipulate that if the state fails to hold the hearing within two months, the project proponent will have the right to organise it. Shreedhar agrees: "Public hearing has to be organised and conducted by the permitter of the project because they are responsibile for allowing the project.'

moef is willing to listen to dissent, says Gupta: "We had suggested the project proponent do public hearing to cut delays. We have also made it mandatory to videotape the entire hearing, as a safeguard.'

Several other changes have been proposed in the new clearance procedures. One of them is to make the local language translation of a detailed summary of the eia document available at the panchayat office. "This is imperative, but why only a summary. For a project worth hundreds of crores, why can't the project proponent spend a few thousand rupees in translating and printing 500 copies of the eia to make it readily available to the local people and experts?' asks Sreedhar. moef has also proposed accreditation of the consultants who will undertake the eia. But who will do the accreditation, the government or the industry, has not yet been worked out.

Drastic changes

moef says it will consult state governments and all the stakeholders before finalising the new clearance processes. But most experts feel that tinkering with the existing provisions is not the way. "Drastic changes are required in the entire process if one needs to address all the social and environmental issues,' says Saldanha. Experts feel that the eia, rehabilitation and environmental issues have to be handled by an independent agency. The industry does not have the ability or the expertise to handle such issues. A suggestion is that the government can charge the industry for it.

Post-clearance monitoring mechanism is another major issue not addressed in the draft. The existing eia has a provision that the project authority submit half-yearly reports to enable the Impact Assessment Agency (moef or the state government) effectively monitor the implementation of the recommendations and conditions subject to which the environmental clearance had been given. It is also mandated that such compliance reports be made publicly available. But is this really followed? "We know that our monitoring and evaluation mechanism leave a lot to be desired,' explains Gupta.

Transparency at each step of the process will ensure that people know the basis and the conditions on which a project is cleared. This will not only help local communities decide about projects coming up in their areas but also make the proponents and the permitters accountable for any problems arising from a project.

Related Content

- Introducing E10 to petrol

- Neuropathogenesis by Chandipura virus: An acute encephalitis syndrome in India

- Green bin charge damaging for environment, says PBP

- Long-distance endosome trafficking drives fungal effector production during plant infection

- Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica from 1992 to 2011

- Propagule pressure and climate contribute to the displacement of Linepithema humile by pachycondyla chinensis