Andaman and Nicobar: Beyond India`s landmass

The Andaman and Nicobar islands (a&n) are thought to be the emergent peaks of a submerged mountain range related to the Arakan Yoma range of mainland Burma. The islands include steep hills, and generally poor soil with little water holding capacity. Flat terrain is extremely limited and the larger islands have long meandering creeks. It is clothed in thick evergreen forests.

The Andaman and Nicobar islands (a&n) are thought to be the emergent peaks of a submerged mountain range related to the Arakan Yoma range of mainland Burma. The islands include steep hills, and generally poor soil with little water holding capacity. Flat terrain is extremely limited and the larger islands have long meandering creeks. It is clothed in thick evergreen forests.

There are more than 350 islands in the Andaman group and over 24 in the Nicobar. Only 10 per cent of the area is inhabi-ted by humans. The islands cover a total area of 8,249 square kilometres (sq km) and a total coastline of 1962 km.

The flora that has evolved here shows closer similarities to those of Burmese, Malaysian and Indonesian origins. At least 32 species and subspecies of mammals, 95 bird species and 23 reptile species are unique to the a&n.In April 2001 an international team comprising Indian, British and Australian scientists conducted a 10-day remote sensing and rapid survey-based study of the coral reefs of the Andaman islands. The survey recorded 197 species of coral, of which an astonishing 111 were new finds for the a&n. One species was completely new to science. Another, found commonly during survey dives, had earlier been reported only from the Philippines.

The new species could touch around 400. This would then compare to the richness of the coral triangle (the area of the greatest marine diversity on earth) comprising the Philippines, Indo-nesia and Papua New Guinea.

Extinct communities The islands are home to 6 indigenous tribal communities. 2 of them - the Shompen and the Nicobari - are of mongoloid origin and reside in the Nicobar group of islands. The other 4 communities are of negrito origin and reside in the Andaman group. These are: the Great Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa and the Sentinalese.

Except the Nicobarese, all the communities are on the verge of extinction.

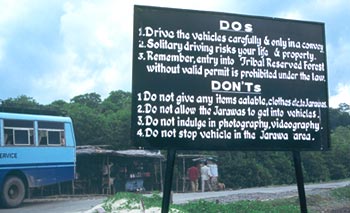

An illogical road The Andaman Trunk Road (atr) connects Port Blair in south Andaman to Diglipur in north Andaman, covering nearly 340 km. Across the world road construction, particularly in rainforest areas, has been one of the biggest reasons for the destruction of forests and tribal peoples. atr is no different.

Work on the road began in 1971, and it was violently opposed by the Jarawas. But the stretch was completed.

The atr is not the best way to travel in the islands. Most settlements are situated on the coast, so marine transport is the most logical mode of transport.

Cheaper, too. A minimum of 12,000 cubic metres of timber is burnt annually to maintain the road. The traffic on the atr isn't heavy enough to justify such maintenance.

Evident hangover A colonial hangover was evident in independent India's scheme for the islands, as a part of which thousands of people were brought from mainland India and settled. In the early years, each settler household was given 1.6 hectares (ha) of flat land for paddy, 2 ha of hilly land for tree crops and 0.4 ha to build a homestead. 12 tonnes of free royalty timber was given for house construction and an additional 5 tonnes for repairs every 5 years.

The islands' strategic location - close to countries in southeast Asia and just north of an important commercial shipping lane - played a role in the settlement scheme. Now India could strengthen its claim over a&n.

The population growth (30,971 in 1951 to an estimated 4,00,000 in 1998) meant constant increased pressure on the forest and the tribes.

October 1977 The Great Andamanese were the first to come in contact with an outside civilisation, the British. Decimated by disease, the tribe consists of 28 individuals today. The Onges fared no better (see: Little Andaman: a chronology). The Jarawa and Sentinalese scrupulously avoided contact, even using violent means to do so.

In October 1977, settlers in the Middle Andaman island witnessed an unfamiliar sight. A group of Jarawas had ventured out of the forest and into modern settlements. This was the first recorded instance of Jarawas seeking to establish contact with the settlers from mainland India. Over the next few months there were more reports of the Jarawas coming out of their forests.

2 theories did their rounds.

Some of the Jarawa, it was reported, were seen to point to their bellies: this was interpreted as expressions of hunger. In the belief that the Jarawas had run out of their traditional food resources (forest-based) and were facing starvation, the local administration led by lieutenant-governor I P Gupta arranged for food relief. Packets containing dry fish, puffed rice and bananas were helicopter-dropped into Jarawa territory.

Others disagreed with the starvation theory. They said the Jarawa who had 'come out' were robust and agile. These people pointed to the experience of Enmey, a teenaged Jarawa boy who was found with a fractured foot near Kadamtala town in Middle Andaman the year before. Local residents - settlers - arranged for his treatment at the G B Pant hospital in Port Blair. When Enmey recovered he was sent back to Middle Andaman where he disappeared into the forest.

The propounders of the Enmey theory said it was he who was largely responsible for bringing his people out.

May 7, 2002

The Supreme Court of India, while hearing a matter related to the a&n environment, accepted the recommendation of a Commission it had appointed to look into the issues involved and passed a set of landmark orders

The Commission had made 25 major recommendations ranging from a ban on all tree-felling in the islands (except for bonafide local islander use), steps to reduce immigration from mainland India, shutting the Andaman and Nicobar forest plantation and development corporation, phasing out monoculture plantations such as that of red oil palm to closing down the atr.

The Bench, comprising chief justice B N Kirpal and justices Arijit Pasayat and H K Sema, suggested that sand-mining be phased out at a minimum rate of 20 per cent every year. Families that had encroached on forest land after 1978 were given a time-limit of 3 months to move to a homestead situa-ted on revenue land. Further, the court ordered that all private saw mills and wood-based industries be terminated with effect from March 31, 2003.

Excerpted from: Troubled islands!, a collection of articles on the Andaman & Nicobar islands by Pankaj Sekhsaria