AIDS hits prime time on Doordarshan

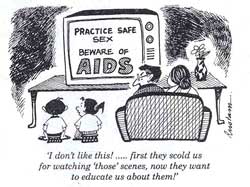

1992 WAS the year when AIDS erupted on TV screens in a big way, prompted by the realisation that being coy about it was only facilitating its spread. Ignorance and preju- dice were both targeted for attack. On Doordarshan, it became a topic for prime-time discussion; on STAR TV, World AIDS Day was marked by a series of films in early December. On neither network did producers mince words, recognising that shilly-shallying can have deadly consequences.

1992 WAS the year when AIDS erupted on TV screens in a big way, prompted by the realisation that being coy about it was only facilitating its spread. Ignorance and preju- dice were both targeted for attack. On Doordarshan, it became a topic for prime-time discussion; on STAR TV, World AIDS Day was marked by a series of films in early December. On neither network did producers mince words, recognising that shilly-shallying can have deadly consequences.

Two of the more memorable programme on Doordarshan were produced by women. Earlier in the year, Juhi Sinha explored the daily agony of two haernophiliacs dying of AIDS, a production whose chief drawback was its long-windedness. More Z' recently, Nalini Singh tackled the question of culpability in what is essentially being seen as a family disease: Should large numbers of women in India remain passive while their husbands infect them? Should they not be made aware of the risks they run from philandering husbands? Should they not then insist their husbands use condoms? In AIDS Dhabba Kyoon?, the filmmaker interviewed a husband who admitted he hadn't even told his wife be was HIV-positive. And, many women from lower income groups pleaded helplessness when their husbands came home drunk and insisted an their conjugal rights, even though they knew these men had visited prostitutes.

Towards the end of the year, Doordarshan telecast a film on AIDS by Shyam Benegal in which the filmweaker fictionalised real-life cases of dwse infected. It was not a particuMy outstanding production but the hriat was effective in conveying selected messages on prevention.

Feminists and activists in India have been perturbed by two aspects of TV coverage of issues related to AIDS. Prostitutes are shown much more frequently as culprits than as victims, which is what they are. And the random shots taken to fill out such TV programmes inevitably convey the impression that it is the poor in the slums and those in the streets who are both more culpable and how his life had changed. He described how he would have a sudden and fleeting loss of strength in his limbs and he had to take medication constantly. Not maudlin at all, but deeply moving.

Even more effective than the documentaries was a late-night film, An Early Frost, which explored the trauma of an affluent, white American family on discovering that both their lawyerson was gay and afflicted with AIDS. It is a moving film; the father instinctively stopping the son from kissing his mother and the young man's sister snatching her son away to keep the nephew from his uncle's embrace. In the hospital counselling group for AIDS patients, one young man complains plaintively that he is getting tired of making friends who keep dying.

Bringing the implications of AIDS alive on the TV screen has two dimensions: repeatedly informing The viewer how AIDScan be spread,and stressing equally that those afflicted need not be denied normal human contact.

Another dimension what is happening in science's fight to stop thisscourge - has been much less in evidence but is more fascinating.One such documentary was featured in STAR TV's week-long series in the first week of December. It explored the major drawback of current AIDS therapy - side-effects and pro- hibitive costs - and surveyed how much the drugs'tested have achieved Lynn Redgrave talking to former far in terms of reducing oppor- tunistic infections and the death rate, besides rating improvements in the body's immune functions.