Ailing Aligarh

in july this year, Rajendra Singh Chauhan, chairperson, Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board (uppcb), announced that the order to shut down 27 hazardous waste-generating industrial units in Aligarh would be postponed . He added that he was seeking legal advice on whether closure should be implemented at all. Chauhan also offered such industrial units a five-year extension against a bank guarantee.

in july this year, Rajendra Singh Chauhan, chairperson, Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board (uppcb), announced that the order to shut down 27 hazardous waste-generating industrial units in Aligarh would be postponed . He added that he was seeking legal advice on whether closure should be implemented at all. Chauhan also offered such industrial units a five-year extension against a bank guarantee.

What he announced conflicts with an October 14, 2003, directive of the Supreme Court (sc), which says that all states must shut down industrial units generating hazardous wastes. The directive was issued under Section 5 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

Why a volte-face now? Obviously, the board has been under pressure. Six months after the sc order, when no action had been taken, N H Hosabettu, member secretary, Supreme Court Monitoring Committee on Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals, came down hard on state pollution control boards. They had to implement the sc order at once: close down units without valid authorisation under the Hazardous Waste (Management And Handling) Rules, 1989, as amended on May 20, 2003. Reads Hosabettu's April 19, 2004, notice: "In case the directions of the Supreme Court are not strictly complied with, the same would amount to contempt of court'.

Acting upon the notice, the uppcb was forced to issue closure orders in May 2004 to 27 industrial units in Aligarh. But now the process has been postponed, blatantly circumventing the sc order. The board's own reluctant closure orders, too, have been transgressed.

Aligarh residents, unhappy with the unchecked growth of units in the town and the subsequent pollution, had welcomed the orders. But their hopes have now been dashed. Former research scientist B D Singh asks, "If the Supreme Court itself has ordered the closure, what legal advice does the chairperson need?' Singh feels that by stalling his board's actions (based on the sc order), Chauhan has created a situation of non-compliance and that could amount to contempt of court.

Good news for brass lobby? But the town's powerful brass exporters should be pleased as punch. In the past 20 years, the brass export market has grown enormously. An estimated 5,000 export units operate in Aligarh and earn the state Rs 700 crore per year.

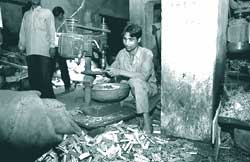

The same units also generate millions of tonnes of dangerous wastes and most of them are located cheek by jowl with people's homes. Rajeev Upadhyay, regional officer uppcb, told Down To Earth that more than 90 per cent of these units were functioning out of residential areas. This is against the Allahabad High Court (hc)'s August 13, 2003, order that no commercial and industrial activities would be allowed in residential areas (earmarked in the Aligarh Master Plan, 2021). uppcb officials in Aligarh are now also saying it is really the Aligarh Development Authority's job to see to the closure of industrial units.

The state government does not monitor local industrial units and even the District Industrial Centre (dic) has no realistic estimates, leave alone figures for the chemicals in use or for the number of units.But Ramesh Chand, general manager dic, admits, "Although there are no exact figures available on this sector, there are approximately 5,000 industrial units in Aligarh, of which nearly 1,100 are registered.' The unregistered units are under no compulsion to manage their wastes; they just throw it out in the streets.

People's health at risk

Chemicals like trichloroethylene are used in electroplating units to remove stains from brass products before they go for final polishing (see Down To Earth