Gunchidharu

With fields of dry crops like ragi and jowar all around, it's not surprising when the trail leads to a tank that has hit rock bottom and has some stalks of corn growing from its dry bed. Even when the tank is full, its water is not enough to meet the needs of all the farmers in the command area. Lean times could mean despair.

With fields of dry crops like ragi and jowar all around, it's not surprising when the trail leads to a tank that has hit rock bottom and has some stalks of corn growing from its dry bed. Even when the tank is full, its water is not enough to meet the needs of all the farmers in the command area. Lean times could mean despair.

Yet the villagers of Kandikere, in Tumkur district, Karnataka, are not despondent. The Hirekere tank in this village is in good hands. If the rains fill it a little more than halfway, the village system of tank management ensures equitable distribution, affirming that good practices can tide over crises.

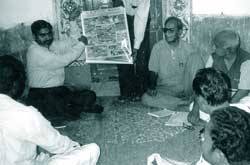

Community manages water The villagers have managed the tank (constructed during the Vijayanagara empire in the 17th century) for over a hundred years. The gunchidharu or village affairs group supervises all local matters from village fairs to the unofficial justice system. Therefore, though the tank is formally under the control of the state's department of minor irrigation, in practice, it is the gunchidharu that looks after the job of water management and distribution.

This group comprises leading members of the village, from all the local castes. The rules for sharing tank water are maintained in a kere pustaka or tank book, as are the distribution records. "For the last three years or so, the water situation here has been really bad. But once the tank gets more than half full in the rains, it will be distributed according to the book, '' says Panchakshariah KG, whose family has been maintaining Kandikere's kere pustaka for years.

Rotation reaches all Hirekere tank's command area is 49.25 hectares. Of this, the official localisation is 30.15 hectares for wet crops and 19.10 hectares for coconut trees and garden plants. The tank's irrigated area is divided into three blocks: Dhalegadhe, Kalagadhe and Honnebayalu. As all the blocks cannot be irrigated even when the tank is full, the villagers have devised a rotation system that is useful especially (as in recent times) when the rains fail. When the tank is two-thirds full, one block is given water for irrigation and when the tank fills up, water is provided to the other two blocks.

"When it rains, we keep track of water filling in the tank, call a gunchidharu meeting and then decide which of the three blocks should be irrigated,'' says Panchakshariah. Paddy is grown during the rains but during the lean season the village switches to crops that require less moisture. The gunchidharu decides what crop can be grown depending on the availability of water.

Local solutions Villagers recall that in the summer of 2002, the water in the tank was enough only to irrigate the Dalegadhe block. But the gunchidharu came up with a solution. Normally, water is provided for the preparation of plots much earlier than transplantation. That year, a decision was taken to conserve water in the tank instead. All the farmers of the block shared the scarcity equally. "When there is water in the tank, there is a good harvest in one or two of the three blocks, water in the wells also fill up and it's a time of prosperity,'' says K Rajkumar who owns land in two different blocks, like Panchakshariah and some other villagers. The tank is used only from November to April. Once it begins to rain, the soudhis appointed for water management in the village check how the tank is filling. The soudhis implement the decision of the gunchidharu. They ensure field channels are cleaned before the water is released and operate the sluice. "We have been growing dry crops for some time as the rains have been failing, but since we have all the records of water distribution, paddy cultivation can start once it rains,'' says Rajkumar. They are aware of local needs from block to block and can ensure proper sharing. The villagers have also formed a water-users association but this has not altered the traditional system of water management here.

Kandikere's example shows how the community can be the best manager of its own, often limited, resources, be it a question of sharing water, or seeds, or the commons. Rather than have a top down system where state bodies dictate arrangements, which then anyway have to be implemented by the villagers, management by the community in a participatory manner is a more equitable and practical solution.