No entry to Dutch plant

FOR the first time in Pakistan, public pressure has given industry notice that it cannot remain free from its environmental responsibility.

FOR the first time in Pakistan, public pressure has given industry notice that it cannot remain free from its environmental responsibility.

A heady new sense of confidence is in evidence among Pakistan"s environmentalists, ever since a 9-month campaign concluded successfully last November. The fall-out of the battle: a move to import a mercury cell-based chlor-alkali plant from Denmark has been halted in its tracks. Instead, the importing unit, Ravi Alkalis, has been forced to settle for the relatively safer membrane cell technology.

With this, Pakistan"s fledgling environmental movement is poised to take wing. The campaign, an important milestone for environmentalists, has alerted Pakistani NGOS to the virtual non-existence of effective national and international environmental laws and mechanisms.

Pakistan"s laws governing industrial pollution are hopelessly antiquated. Most of the air and water quality acts were promulgated either pre-Partition or in the "60s. Even the latest environmental act which seeks to. regulate industrial emissions-the 1983 Pakistan Environmental Protection Ordinance-lacked teeth for a long time. The key concern of environmentalists is the need for revision of the national environmental quality standards and making them more industry specific, or establishing ambient quality standards. Similarly, - though the Environmental Protection Agencies (EPAS) have begun functioning, they do not have the ability to monitor environmental compliance by industry because of lack of technical expertise.

Pakistan"s glaring record of environmental laxity had made it an ideal site for Dansk Sojakagen (DS) Industries of Copenhagen, Denmark, to send its old chlor-alkali factory. The DS plant, built on Islands Brygge in Copenhagen in 1935, had an abysmal environmental track record. It was alleged to have dumped around 50 tonnes of mercury into the Copenhagen harbour - with the consequence that fishing is still prohibited in the Greater Copenhagen coastal areas. The factory had also caused much hardship to the people of Islands Brygge who were for bidden to grow vegetables because mercury emissions from the plant had contaminated the soil in areas adjoining the factory.

A red-alert was sounded when the Pakistani NGO, Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), received news from Greenpeace International about the imminent transfer of this plant on March 28, 1994. In its tip-off to the SDPI, the international environmental organisation warned that the mercury cell technology was the "oldest and dirtiest" of the 3 major technologies for chlor-alkali production. It had already been discredited worldwide on accouni of numerous health hazards associated with mercury poisoning, such as nervous disorders, nightmares and insanity. In western Europe, the havoc wreaked by mercury clontarnination had led to a decision"-by all Paris Commission countries (including Denmark) to phase out the mercury cell technology.

Chlorine, as Greenpeace pointed out, was also under severe attack the world over for possible ill effects such as cancer, birth defects and liver damage. "In the long run, we believe all production and use of chlorine will be phased out. Meanwhile, the transfer of this notoriously dirty technology and equipmerit for chlorine production to Pakistan is precisely the wrong kind of technology transfer for the POST-UNCED (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development) period," warnedKenny Bruno, a toxic tech- nology transfer expert with Greenpeace in New York.

Soon after the news of the transfer was made public in both the countries, SDPI, Greenpeace and several Pakistani and Danish NGOS launched a campaign to halt the shipment. The Copenhagen Environmental Protection Agency (CEPA) categorised the equipment as chemical waste in March 1994, in the hope that under the Basel Convention-which prohibits the export of hazardous waste from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries to non- OECD countries-it would not be allowed to leave Denmark. Adding her voice to the opposition, Charlotte Ammundsen, the mayor responsible for the environment in Copenhagen said: "I think that reconstructing the plant for chlorine production is a problem in itself. If the old plant is to be operated by people who do not know it well, there are considerable risks of discharge of both mercury and chlorine." Much to the dismay of environmentalists in Pakistan and Denmark, a loophole in the Danish law was exploited to the hilt by DS Industries and Ravi Alkalis-whose name was uncovered by Greenpeace-to push through the transaction. Under Danish, law, a facility cannot be classified as hazardous waste if it is demonstrated that it can be reassembled for production purposes.

CEPA, therefore, found its hands tied when DS Industries demonstrated that the sale would lead to resumption of production. Confronted with documentation from Ravi Alkalis that the plant would operate in Pakistan and a no-objection certificate from the" Punjab EPA, the CEPA had little option but to declassify the plant equipment as hazardous waste on May 9, 1994. A scathing comment in Information, a Danish newspaper, described the gaping holes in Danish export legislation: "The export of environmentally hazardous waste and of technology relevant to security is controlled by the authorities. But environmentally damaging technology can freely be exported to developing countries."

The official response in Pakistan too made environmentalist groups see red. Despite repeated attempts, the Punjab EPA turned a deaf ear to their queries about the proposed plant site, pollution control measures to be adopted by Ravi Alkalis, the EPA"s capability to monitor effluents or emissions from the factory and punitive measures for breach of national environmental quality standards. Similar apathy characterised other government institutions such as the Environmental Protection Council and the Ministry of Environment and Urban Affairs.

After an initially positive response to the high decibel media campaign on the dangers of the mercury cell technology, the Pakistan Senate also soft pedalled the import of the hazardous plant. On July 24, at the behest Of SDPI, the issue was raised in the Senate. It was then referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Urban Affairs. The Senate skimmed over the whole agonised debate over environmental risks, by taking on faith Ravi Alkalis" argument that the plant would adhere to national environmental quality standards and hazardous effluents would not be allowed to escape into the environment. The plant was, therefore, given a green signal by the Senate without any independent analysis.

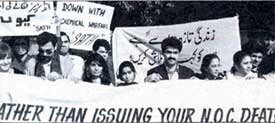

From mid-October onwards, the anti-plant lobby moved rapidly. Based on a critique, of the Standing Committee"s paper by the University of Exeter"s Earth Resources Centre, UK, the SDPI, joined by other Pakistani NGOS such as Shirkat Gah, Sungi Foundation, Strengthening Participatory Organisations (sAP), World Conservation Union, Pakistan and the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) accelerated their campaign. The NGOs- with strong support from Greenpeace sent off letters voicing their apprehensions about the plant, to concerned officials both in Pakistan and Denmark. Danish workers who7had been employed at the"bs plant and nearby residents also wrote to the Danish government about the monumental problems that they had faced for 20 years.

Early last November, Greenpeace representative Anne Leonard organised meetings with the top brass of the Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Urban Affairs, and the Federal and Punjab EPAS. She also visited the proposed site of the plant at Sheikhupura and unearthed some disconcerting facts: the surrounding land was very fertile and the 35,000 inhabitants living in the vicinity of the Ravi Channels Link Road were completely in the dark about the implications of the plant.

In a dramatic gesture of solidarity, local Danish activists began a 24-hour candlelight vigil on November 9 in Copenhagen as the mercury-contaminated equipment for the plant was loaded into containers for shipment to Pakistan. The shipment was to reach Pakistan by the first week of December. Danish dock workers and Pakistani trade unions also voiced their condemnation of the transfer by refusing to be associated with the loading and unloading of the shipment.

In the face of escalating protests, the Senate Committee on Environment agreed to re-examine its earlier decision to allow the hazardous plant into Pakistan. A hearing was fixed for November 22, 1994. That date proved momentous. At the hearing and later at a press conference, the top brass of. Ravi Alkalis announced their intention not to press ahead with the import of the mercury cell and mercury contaminated equipment and instead upgrade the technology to membrane cell. Under Danish law, such unused equipment reverts to being classified as chemical waste and can not be exported under the Basel Convention.

As the initial euphoria over the successful campaign wears off, Pakistani NGOs are only too aware of the challenges that lie ahead. The country"s close shave with the highly toxic DS plant has put several concerns high on their agenda: pushing for a commitment from the North that obsolete technology will not be dumped in Southern countries; national legislation to ban import of hazardous/ obsolete technology; mechanisms to screen incoming technology, revision of the National Environmental Quality Standards; and a more rigorous and independent Environmental Impact Assessment.

In the short term, a grou of 5 NGOS has agreed to set up an Environment Monit "oring Group (EMG). The EMG has a clearmandate-to ensure that Ravi Alkalis fulfills its commitment to use a safer technology to produce chlorine and to monitor the chemicals industry.

The long term problems remain. Says Bruno: "Membrane cell technology is definitely an improvement over mercury cell technology from the perspective of the local environment, because mercury emissions and contamination are completely eliminated."

"However, the risk of chlorine gas escapes-which can kill or severely injure people-remain the same. In addition, the chlorine itself, which is so often incorporated into toxic organochlorine chemicals, is still the root of much of our toxic contamination," adds Bruno.