Raw Deal

The festivities of January 1, 2002, signified the sealing of a pact between the Kerala government and the Adivasi Dalit Samara Samithi (agitation council) on October 16, 2001. The agreement guarantees allotment of one to five acres (around .5-2 hectares) of land to all landless tribal families in the state and implementation of a development support scheme for them over the next five years. For the present, the tribal body has taken the authorities at their word and suspended its 48-day struggle.

The festivities of January 1, 2002, signified the sealing of a pact between the Kerala government and the Adivasi Dalit Samara Samithi (agitation council) on October 16, 2001. The agreement guarantees allotment of one to five acres (around .5-2 hectares) of land to all landless tribal families in the state and implementation of a development support scheme for them over the next five years. For the present, the tribal body has taken the authorities at their word and suspended its 48-day struggle.

However, even before it has got off the starting block, the trdm is mired in a controversy over the status of the land being given. Top officials of the Kerala Forest Department (kfd) dub it as yet another betrayal of adivasis because they are being promised forestland and uncultivable tracts. It is felt that the tribal communities may soon have to vacate many of these plots, either for want of legal clearance or on account of crop failure. Then there is the spin the government's give-and-take approach has imparted to the issue. Most of the tracts identified so far are ecologically fragile and as per a legislation that is awaiting clearance, all such areas will be deemed fit to be vested. The authorities may, therefore, end up reclaiming the very land they have handed over to the indigenous people.

The master plan document lists forests mainly as a means for resource extraction and all natural forests (50 per cent of the total woodland) are set to be clubbed under the Participatory Forest Management (pfm) programme. Consequently, the tribal people will be saddled with additional responsibilities in terms of operating in non-intervention zones (gene pool reserves) and non-timber forest produce (ntfp) areas. A history of hostility between the tribal communities and the kfd could also have a bearing on the future of the scheme.

Land blight While the government had initially claimed that there were 11,000 landless tribal families, a trdm team has put the number at 53,472. To honour its promise the administration, therefore, needs over 53,000 acres (more than 21,448 hectares) of cultivable land. By November 2001, officials had identified around 14,569 hectares (ha). But the bulk of it is vested forestland. Assigning such tracts for private ownership is not permissible under the Forest Conservation Act (fca), 1980.

Ironically, the provision in a 1971 Act passed by the state to assign 23,058.63 ha of vested forestland to tribal families for cultivation was not implemented. Had this been done prior to the tightening of forest laws in 1980, the issue would have been resolved decades ago without snowballing into the ongoing social conflict, feel members of the agitation council led by C K Janu.

There is also the question of the current ownership of land. "We have records to prove that the tracts for which title deeds have been given are revenue lands,' says the district collector of Idukki. Though this contention has been challenged by the kfd there are many who believe that there is a tacit understanding between the forest department and revenue officials to protect the interests of the land mafia in the state. Incidentally, voluntary organisation Thiruvankulam Nature Lovers' Movement has moved court against the revenue department claim.

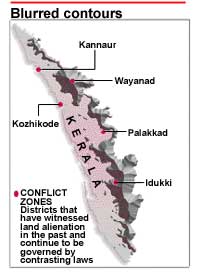

A recent report of the Legislative Committee on Government Assurances (1998-2000), chaired by legislator Izhaq Kurikkal, reveals that Tata Tea Limited alone holds over 20,234 ha of illegal forestland in Idukki. Whereas such lands have been excluded, even steep forest hill slopes such as those at Mankulam (8094 ha) have been included in the master plan for handing over to adivasis (see map: Blurred contours). Nalla Thambi Thera, an activist and non-adivasi doctor practising in Wayanad, points out that the land earmarked in the Marayoor and Kundala areas of Idukki district is uninhabitable.

Sources hint at a conscious effort on the part of the authorities to avoid touching high-value revenue properties under the control of the rich and the influential. In fact, state forests minister K Sudhakaran has admitted to a nexus between officials, government pleaders and the land mafia.

The revenue and forest departments are now carrying out a joint survey. "We have sought the Union government's permission to clear 10,117 ha of vested forestland,' says the chief minister. "Legal means will be found to distribute land to the poor tribal communities,' he adds (see box: Natives turn restive). But the general feeling is that this would be an extremely difficult task. Even advocate general M Ratna Singh is understood to have advised the administration against carrying out the exercise in its present form, warning that any such attempt would "unduly expose government officials to punishment under section 3 (b) of the fca'.

Meanwhile, the adivasis find themselves precariously perched between conflicting claims; they are hopeful but their patience is wearing thin. "Whatever be the obstacles and persuasions, we are now determined not to give up the promised land,' says Ashokan, a tribal youth from Marayoor, stridently. Aliens on home turf

Last August, when they set up

Related Content

- Order of the Supreme Court regarding installation of flue gas desulfurization units in thermal power plants, 29/04/2025

- Order of the Supreme Court of India regarding steps taken to control air pollution in Delhi NCR, 12/12/2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding the presence of a garbage receptacle point/dhalao near a blind school, Delhi, 29/11/2024

- Order of the Supreme Court of India regarding severe air pollution in Delhi NCR, 18/11/2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding use of chemicals in cleaning water bodies, Pune, Maharashtra, 05/04/2024

- Draft Electricity (Third Amendment) Rules, 2024