Scales out of balance

The voyage towards consensus building on ocean resources has always been protracted. Take the 3rd United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which began in 1972. It took nearly 10 years to reach consensus on the single negotiating text. On the appointed date -- 10 December 1982 -- the US Government backed out of signing the Convention. Consequently it took 12 years to ratify and finally came into international force only in November 1994.

The voyage towards consensus building on ocean resources has always been protracted. Take the 3rd United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which began in 1972. It took nearly 10 years to reach consensus on the single negotiating text. On the appointed date -- 10 December 1982 -- the US Government backed out of signing the Convention. Consequently it took 12 years to ratify and finally came into international force only in November 1994.

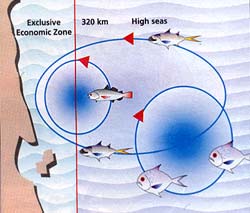

One important unsettled UNCLOS issue related to high seas fisheries -- fishing undertaken outside the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in territory referred to as the common heritage of humankind. The concerns within this issue include unregulated fishing, over-exploitation, excessive fleet size, reflagging of vessels to evade controls, use of non-selective gear, unreliable databases and lack of cooperation between States.

All these became particularly contentious with regard to fishing for straddling and highly migratory fish stocks. Straddling stocks are fish that occur naturally both within and beyond areas under national jurisdiction. The most well known is the Atlantic cod in Canada, which was sustainably harvested for hundreds of years before being devastated by 40 years of bottom trawling. Highly migratory stocks are fish such as tuna, that migrate largely between areas under national jurisdiction.

Problems pertaining to these stocks were raised at the Rio Summit in 1992 and hence prompted the call for an intergovernmental conference under the auspices of the United Nations to promote effective implementation of the provisions of UNCLOS in this regard.

Preserving a common heritage

The United Nations Conference on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, has already held five gruelling sessions from July 1993 to March-April 1995. The Conference, in the words of Chairman, Satya Nandan of Fiji, has already achieved broad agreement on almost all its provisions and an agreement, if all goes well, is expected to be signed at the final session due to be held at New York in July-August 1995.

The major interested parties at this Conference are the coastal states on the one hand and the distant water fishing nations on the other. The former group, which is the largest, is led by Canada and the latter, comprising the European Union (EU), Japan, China, Korea and Poland is led by the EU. While the coastal states want greater control on high seas fishing activities, the distant water fishing nations, are averse to any control on their fishing activities by the non-flag States. Despite these conflicting interests, the draft Agreement produced at the end of the March-April 1995 session, within the framework of rights and duties of states as specified in UNCLOS, attempts to further define and develop the duties of flag and non-flag States in the high seas. The draft agreement creates 3 essential pillars. Firstly, it provides for principles and practices on which better management of stocks should be based. Secondly, it tries to create a mechanism to ensure that conservation and management measures adopted for the high seas are adhered to, complied with, and not undermined by those who fish in those areas. And thirdly, it provides for quick and peaceful settlement of disputes.

The agreement seeks non-conflicting conservation and management arrangements both within and beyond the areas under national jurisdiction (EEZs), by coastal states and distant water fishing nations, based on the precautionary approach. In keeping with this, the draft stresses that "the absence of adequate scientific information shall not be used as a reason for postponing or failing to take conservation and management measures." It consequently stresses the importance of collection of relevant data and information. The principles and practices for better conservation and management also include the development and use of selective, environmentally safe and cost-effective fishing gear and techniques, elimination of overfishing and excess fishing capacity and enforcement of conservation and management measures through effective monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms.

The draft agreement recognizes that better management of stocks is the responsibility of all states irrespective of jurisdictional considerations. It therefore recognises the right of non-flag states to board and inspect vessels in support of sub-regionally, regionally or globally agreed conservation and management measures. By giving enforcement powers to both flag and non-flag states, the Conference hopes to achieve better compliance with and effectiveness of these measures.

A revealing sense of urgency

The significance of this Conference arises mainly from the fact that this is the first major international treaty negotiation to be held on fisheries after the realization by the world community that the marine fisheries resources are indeed quite limited in quantity and vulnerable to excessive pressure and wasteful fishing activity. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation's State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture released in March 1995 reports that "about 70 percent of the world's marine fish stocks are fully to heavily exploited, overexploited, depleted or slowly recovering." It also points out that "between 17.9 and 39.5 million tonnes of fish a year are discarded at sea." Against this grim backdrop, the draft Agreement does not leave anything to chance and indeed shows a sense of urgency by strongly building in a realistic time factor into the implementation of conservation and management measures.

One of the salient aspects of the draft Agreement as explained above is the importance it attaches to the precautionary approach to management. This is a major departure from current practice in fisheries management where action is usually delayed until proper scientific data is available, by which time the stock is on the verge of ruin! In the case of new or exploratory fisheries, the draft Agreement prescribes conservative conservation and management measures. Further development of a fishery, according to this prescription, should be attempted only if data supports such a development.

Thee other major departure from established practice relates to the traditional flag state principle which accepts that on the high seas only flag states have jurisdiction over their vessels. The draft Agreement grants enforcement power to non-flag states. However a balance is yet to be struck between the rights of the flag states and enforcement by non-flag states, should the flag state express reluctance or unwillingness to take action against their vessels for violation of regionally agreed conservation measures. The EU and Japan have, however, taken strong exception to the right of non-flag states to board and inspect vessels. They maintain that the right to board and inspect vessels on international waters should be worked out through regional arrangements and not global principles. Such objections from powerful distant water fishing nations may block progress of the Conference at its final session in July 1995. The Chairman of the Conference, however, feels that such objections at the final stage could force a vote on the agreement.

The draft Agreement also makes unprecedented provisions for excluding non-member states from fishing in areas of the high seas under regional and sub-regional entities. In order to prevent non-members of sub-regional and regional fishery management organizations or arrangements from undermining management measures, the Agreement forbids such states from allowing their vessels to operate in fisheries that are subject to conservation and management measures under this Agreement. In other words, only members of regional and sub-regional organizations and arrangements can allow their vessels to operate in areas under the jurisdiction of such organizational arrangements. Countries like Taiwan (which are not members of the UN system) that have proven fishing capabilities on the high seas, will have to restrict their fishing activities in areas of the ocean that are not under any regional or sub-regional management authority.

This measure has important implications for developing states that do not yet have any sub-regional or regional fisheries organization, to think in terms of establishing such mechanisms irrespective of their fishing capabilities on the high seas. The future of fisheries development and management lies in the creation of a mosaic of such regional organisations which club together the EEZs of the participating states under the rubric of international treaties. The possibility of a SAARC fisheries organisation which makes ecological and economic sense needs to be explored. The national and international NGOs who were present represented a variety of interests including environment, fishworker, development and industry. These included the Greenpeace International (Fisheries Campaign), International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (Madras), Women and Fisheries Network (Fiji), Oceans Caucus (Canada), CREDETIP (Senegal), Worldwide Fund for Nature (UK). Individually and collectively these NGOs have been able to influence the drafting process through their direct interventions and lobbying efforts.

Under mechanisms for international cooperation concerning straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks, the draft Agreement further allows for opportunity to NGOs to participate in meetings of sub-regional or regional fisheries management organization or arrangements and timely access to information of such entities. This greatly enhances the transparency of the Agreement.

Protecting the fishworkers

The fishworkers' organisations from the South have reason to feel happy about the outcome of the conference because many of their concerns in relation to protecting access to resources, laxity of flag state responsibility, overcapitalisation and overfishing, non-selectivity of fishing gear and techniques have been addressed to a certain degree in the draft Agreement.

Thus in Part VII of the draft Agreement, dealing with the special requirements of developing states, the Agreement underscores "the need to avoid adverse impacts on and ensure access to fisheries by subsistence, small-scale, artisanal and women fishworkers as well as indigenous peoples in developing states". While establishing conservation and management measures for straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks.

The Article on General Principles also includes, as a result of lobbying by environmental and fishworker related organisations, a new paragraph on "taking into account the interests of artisanal and subsistence fishers" while giving effect to the duty of the States to cooperate in accordance with the UNCLOS. It also includes the need to "promote the development and require the use of selective, environmentally safe and cost-effective fishing gear and techniques."

A new paragraph in Article 20 on international cooperation in enforcement could also help several coastal fishing communities dependent on highly migratory fish stocks like tuna. They could expect redressal for violations by flag state vessels who engage in unauthorized fishing within their national waters. The paragraph makes it obligatory for the flag state to take action against such vessels at the request of the coastal state, and also to cooperate with the coastal state in taking appropriate enforcement action. The flag state may even have to authorize the coastal state to board and inspect such vessels on the high seas.

In the context of the current agitation of Indian fishworkers against the redeployment of fishing vessels from the North into our waters under the guise of 'Joint ventures,' the measures in the draft agreement are neither strong enough nor comprehensive enough to strike at the root causes. Though the General Principles advocate "measures to prevent or eliminate over-fishing and excess fishing capacity" it does not require the elimination of non-selective fishing gear and techniques. This is in spite of common knowledge and scientific evidence about the responsibility of bottom trawlers for causing the dramatic collapse of cod stocks in the Grand Banks off Canada. The draft Agreement also fails to address the issue of the large fisheries subsidies, offered by developed countries to their deep sea fleets, which run in the tens of billions of dollars a year and contribute significantly to overfishing and excess vessel capacity.

While the draft Agreement recognises the need to establish consistent measures for conservation of straddling and highly migratory stocks whether they are fished inside or outside the EEZs of the States, the legal requirement to apply these measures strictly inside the EEZs is missing. This can indeed be counterproductive in the long run considering that straddling and highly migratory fish stocks in the high seas account for only 10 to 20 per cent of the world's fisheries output.

Urgency in the air

The draft agreement also does not make any mention of safety and working conditions on board fishing vessels, and attempts to include provisions in this regard under the flag State responsibility were turned down by the Chair on the ground that these are precincts of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Legitimisation of regulatory regimes by all stakeholders is important for the efficacy of law. Making, or reiterating, provisions to protect workers' rights would greatly enable legitimacy of the regulatory framework from fishworkers, and they are indeed a major stakeholder in any fishery around the world.

Had the provisions in the draft Agreement been incorporated in UNCLOS in 1982, it may have averted in a big way the critical situation facing world fisheries today. There is thus an overall sense of urgency in the air. The fisheries ministers from around the world issued a ministerial declaration in March 1995 called the "Rome Consensus on World Fisheries" and an intergovernmental Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries is being drafted by the FAO. Against this background, though still deficient and too little too late, the draft Agreement is a small step in the right direction. It is however, still too early to be complacent about even this small achievement. There is the serious risk that the text may be substantially watered down at the final session of the Conference in July 95. The fact also remains that ratification of the treaty by a sufficient number of states (40 ratifications are needed) may well take us to the dawn of the next century.

Related Content

- Managing the seasonal variability of electricity demand and supply

- State of global water resources 2022

- Joint committee report on silica sand washing plant, Prayagraj district, Uttar Pradesh, 03/02/2023

- China's route to carbon neutrality: perspectives and the role of renewables

- Key factors for successful development of offshore wind in emerging markets

- GEO-6 for Youth