To hell and Back

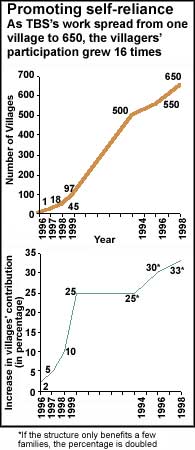

Ask anyone in the 650 villages in Alwar where tbs has worked in the past 13 years. The story of the later part of this century will follow the same course. Lack of vegetation led to land degradation. Monsoon run-off washed away the top soil. Crops failed regularly and agriculture was fast slipping into memory. The work-force migrated to cities to make ends meet. Women trudged long distances to fetch a mere pot-full of water. Life was difficult, and it seemed endless.

Ask anyone in the 650 villages in Alwar where tbs has worked in the past 13 years. The story of the later part of this century will follow the same course. Lack of vegetation led to land degradation. Monsoon run-off washed away the top soil. Crops failed regularly and agriculture was fast slipping into memory. The work-force migrated to cities to make ends meet. Women trudged long distances to fetch a mere pot-full of water. Life was difficult, and it seemed endless.

“Nange pahad dur daraj” (naked hills all around). That was how Rajendra Singh saw the hills of the Aravalli range in Alwar in 1985. The region, which was once sustained by the ecosystem of the Aravalli, looked war-ravaged. It was rare to find people in the age group of 17-37 years. All of them fled their villages to urban centres such as Delhi and Ahmedabad in search of employment. In 1985-87, 80 per cent of the men were migrating from the Thanagazi block. “For years the villagers remained ‘all-women villages’,” remembers the 80-year-old Dhanua Baba of Koylala village (see box on p40: The seeker).

“There was not a single blade of grass for grazing cattle. One could stumble upon carcasses of cattle,” Rajendra Singh remembers. Crop yields were less then paltry. Barely three per cent of all cultivable area was irrigated. This was alarming as about 90 per cent of villagers were marginal farmers with their own land. “For years I cultivated my one hectare of land. I had to spend Rs 10,000 and the return was some Rs 500. I was caught in a debt trap. In 1984, I migrated to Ahmedabad to pay back the loan,” says Ram Singh of Toda village. “In the seven years that I took to clear the debt, my land had become barren.”

That was the fate of the entire region. “The richest and the poorest of the village were the same as far as the economic condition was concerned. There was not a bucket of water for irrigation. The wells were dry. Like the agricultural lands the villages were also dried of life,” says Mangu Ram Patel. In Gopalpura village, even the zamindar (landlord) and his son migrated in search of work.

“Ecological destruction was causing economic and social degradation,” says Rajendra Singh. The illiteracy rate in the Thanagazi block in the mid-1980s was 85 per cent. Attendance in schools was as low as two to three per cent.

When mountains erode

Rainfall here is quite low (600 millimetre, of which 500 mm falls during the monsoon). The arid slopes of the Aravalli are not suitable for intensive cultivation. The food security of the area also depends on forests, grasslands and wildlife, which traditionally had common property status. They were managed through a set of rules decided by the villagers.

S S Dhabariya, former head of the remote sensing division of the Birla Science and Technology Centre, Jaipur, observes: “The Aravalli hill region had thick forest cover during earlier decades. It helped in protecting the soil cover and water aquifers and provided favourable conditions for the regeneration of tree-stock and pasture.”

“The hills, as far as the eye could see, were full of trees, leopards and tigers. Now, after some 60 years, all that has vanished. Not a single bird nests here. There are rocks all around,” says Sunder Bai, an 80-year-old woman of Bhaonta village. In 1985-86, a mere six per cent of the Alwar district’s total area was under forest cover.

In 1980-82, only 1.7 per cent of the area specified as forest in Rajasthan had actual green cover. Remote-sensing data showed that the Aravalli was brown in colour. In 1984, only 28.6 per cent of the notified forest area on the Aravalli was green