Industrial devil ution

Industrial survey statistics tell you that more than one-third - 36.3 per cent - of the total value added by to the raw materials through manufacture in the factory sector of the country comes from Maharashtra (23.66 per cent) and Gujarat (12.64 per cent). Easily, the two most industrialised states of India. Governments of both the states claim they have created immense prosperity in the region. But statistics do not tell you the real story of thousands of workers and farmers. Aniruddha Mohanty is one of them.

Industrial survey statistics tell you that more than one-third - 36.3 per cent - of the total value added by to the raw materials through manufacture in the factory sector of the country comes from Maharashtra (23.66 per cent) and Gujarat (12.64 per cent). Easily, the two most industrialised states of India. Governments of both the states claim they have created immense prosperity in the region. But statistics do not tell you the real story of thousands of workers and farmers. Aniruddha Mohanty is one of them.

Mohanty has been working in the Daru Khana shipbreaking yard of Chembur for the past 15 years. It is a life without any dignity due to a living being. Everyday for 8-10 hours he inhales toxic fumes from the abandoned ships that he breaks. The fear of explosion looms large. His best friend died last month in an explosion while breaking a ship. "In the past 15 years, I have got tuberculosis three times. The doctors say I have to quit this job and to shift to a cleaner place," he says. He stays in Deonar, Maharashtra's largest solid waste dumping ground. In violation of a Mumbai High Court order, prohibiting burning of wastes, wastes are still burnt in Deonar. For Aniruddha, clean air is an impossibility.

Drive down the Mumbai-Pune highway and you will witness the horrible truth of industrialisation. Hundreds of industrial units dealing with chemicals and fertilisers dump their sludge along the roadside. Chimneys emit gases that make breathing difficult. "Industrial units never stop polluting, and people cannot stop working for them. So, it is a treadmill that ends only with a painful death," says Rajesh Panicker, an industrial worker of Panvel in Maharashtra.

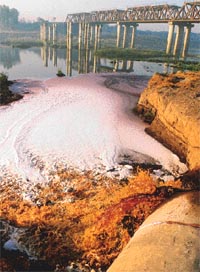

A few hours of travelling northwards of Mumbai will take you to the Vapi Industrial Estate of southern Gujarat. At Kolak village, about 15 km away from the estate, you will get statistics of a very different kind. "Sixty people have died of cancer in the village in the past 10 years, while 20 others are fighting a losing battle," says Ganpat B Tandel, former sarpanch (head) of the village council, who has been vehemently opposing pollution of the Kolak river by the industrial estate. Nearly 20 years ago, cancer cases were not so rampant. But factories of the estate, which produce pesticides, agrochemicals, organochlorines dyes and dye intermediates, have been dumping untreated effluents in the river. Most residents of the village are fisherfolk who eat fish from the river.

"The organochlorines and other persistent organic pollutants (POPS) in the industrial effluents are known carcinogens," says Michael Mazgaonkar of the Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti (PSS), a Gujarat-based non-governmental organisation. Take the case of Deviben Tandel, who had cancer. On December 31, 1999, when thousands of people who use products manufactured at Vapi would have been celebrating new year's eve, the 50-year-old resident of Kolak quietly died. Four months ago, her elder sister had died of cancer.

As per a Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) action plan for Vapi, factories cannot dump effluent in the rivulet Bhil Khadi but have to send it to a common effluent treatment plant (CETP). "But hundreds of industrial units do not treat their wastes as per the inlet parameters of the CETP, and are releasing untreated effluents into the Bhil Khadi. It ultimately meets and pollutes the Kolak river and the sea," says a CPCB official.

Nainabhen Tandel, sarpanch of the village council, says: "On many occasions, we have caught tankers directly dumping effluents in the river." The fish catch in the coastal areas has gone down considerably. Says K H Makrani, vice-president of the Daman Fishermen Association in Valsad district of Gujarat, "We don't get fish catch in the seashore areas. So, only those fisherfolk who can afford to go as far as 12 km inside the sea are continuing in this business."

There are innumerable stories like these that go unheard. Invariably, those worst hit by industrial pollution are either rural folk who are unaware of its effects or workers who earn their living from the polluting factories. But more than the polluting industrial units, the blame goes to regulatory agencies - state pollution control boards (SPCBs) and state industrial development corporations - that were created to control and monitor industrialisation. Instead, these agencies have been reduced to mere rubber stamps to promote industrialisation at a frenzied pace. The industrial system has been reduced to a state wherein it makes better business sense for industrialists to carelessly dump hazardous waste rather than set up mechanisms to deal with it.

So, what are the people doing to save themselves? Actually, not much right now. But, not too long ago, there was hope of battling out the pollution juggernaut through the courts and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Finding out that there was absolutely no point in knocking at the doors of government agencies - there is a clear bias in favour of the industry throughout the government machinery - those affected by pollution rallied behind NGOs. A spate of public interest litigation (PIL) saw the polluters being dragged to court.

But the lack of initiative on the part of the implementing agencies tired out the public spirit. In 1995, the Gujarat High Court ordered the closure of 756 industrial units in Vatva, Narol, Naroda, and Odhav, asking them to compensate the villages affected by pollution through discharge of untreated effluents. Many of these units are operating even today and are still polluting. "The failure of the court had an extremely damaging effect as even the last institution of democracy failed to check pollution in Gujarat," laments Girish Patel, an advocate in the Gujarat High Court.

In Maharashtra, the problem is compounded by the absence of credible data. "It is difficult to find any data on the environmental status. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board does not come out with any study on pollution. So the people do not have strong baseline data to contest the powerful industry lobby," says T N Mahadevan, a scientist who is also the secretary of Society for Clean Air, a Mumbai-based ngo. "Lack of information paralyses the battle against pollution."At present, it's all quiet on the western front. And dirty.