"There is no fish"

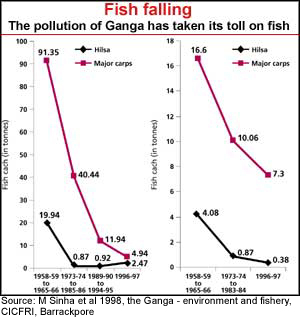

Pollution is one of the biggest killers of inland fish. And traditional fisherfolk are worst affected,says K Gopakumardeputy director-general (fishery)Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)New Delhi. Data from the Central Inland Capture Fisheries Research Institute (CICFRI)Barrackporeshows that fish catch in most riverine fisheries is declining. The Gangafor examplereceives mostly untreated effluents from 29 cities70towns and thousands of villages. This is showing up in the fish catch. Annual inland fish landing of major carps in Allahabad and Bhagalpur has drastically come down (see graph: fish falling). Moreovermass fish deaths have been reported in Gomtia tributary of Gangaon many occasions.

Pollution is one of the biggest killers of inland fish. And traditional fisherfolk are worst affected,says K Gopakumardeputy director-general (fishery)Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)New Delhi. Data from the Central Inland Capture Fisheries Research Institute (CICFRI)Barrackporeshows that fish catch in most riverine fisheries is declining. The Gangafor examplereceives mostly untreated effluents from 29 cities70towns and thousands of villages. This is showing up in the fish catch. Annual inland fish landing of major carps in Allahabad and Bhagalpur has drastically come down (see graph: fish falling). Moreovermass fish deaths have been reported in Gomtia tributary of Gangaon many occasions.

It is the same story for every river in India. The Periyar in Kerala has been severely affected due to pesticidesindustrial waste and sand mining. Dyeing industries have almost killed the Noyyal in Tamil Nadu. "Five species of fish that used to be abundant in Assam's waterbodies are now raresays Ashok Bishaya, a prominent member of the Koiborto fishing community in Guwahati. The Yamuna is nothing but a tiny sewage drain with zero aquatic life as it leaves Delhi, says P V Dehadrai, former director-general (fishery), ICAR, who has done a study on the status of fish and fisherfolk.

Villagers of Khunti village downstream of the Hirakud dam on the Mahanadi in Orissa say they catch less than half the amount they used to catch in 1950s and 60s.Fish catch has come down to 20 per cent in the last three decades and earnings are down to less than 50 per centsays Bhagwati Mukhiya, a mallah and resident of Kusheshwersthan.

Caught in the net

The traditional fisherfolk share an intricate relationship with nature. It is their annadata and they cannot afford to play with itsays Bishaya. Non-fishing communities, however, go for maximum extraction.One of the factors for overfishing is the duration of the leasewhich is one yearsays Dehadrai. The leaseholder wants to extract as much as possible from the river.

The problem gets worse with the use of fishing gear. While the traditional fisherfolk's gear captures only a particular size of fish, the rich contractors use massive, but fine mesh nets - most of them made from mosquito nets. For example, the one used in Bihar, Mahajaal, is more more than 50 metres wide and about 750 metres long. It needs at least three boats and 15 people to operate. But just three people are needed to operate the traditional nets. Mahajaals sweep entire stretches of the river without even sparing a fingerling. These are expensive - they cost about Rs 60,000 and only the rich contractors can afford them. They are banned too. And small nets are no match for Mahajaals.We carry our small nets in the bags. We are ashamed to show themsays Bajrangbali Sahni, a resident of Kagjitola.

With a dwindling fish population, people have resorted to devious methods to catch fish. In Bihar, rich contractors are known to poison the river at one point and collect the dead fish that is available.About 100 grammes of parmar (aldrin) can kill fish for up to 3 km. It does not even spare the eggs and the living organisms the fish depends onsays Gangaram Sadha of Deoka village, Madhubani. The use of dynamite sticks to blow up a portion of the river is also a common practice in many rivers.

Norms are flouted with impunity. There is a ban on fishing up to 3 km downstream of the Farakka barrage in Bihar during monsoon, the breeding period of fish. However, one can see hundreds of boats fishing up to 100 metres of the barrage, says R K Sinha, professor at Patna University.The moneyed section of the fisherfolk are hand in glove with officials and security personneladds Sinha.

Dammed problem

Developmental projects like dams, barrages, embankments and roads have also contributed to fish loss. Reservoirs created after damming the rivers not only block the routes of migratory fish like Hilsa, which move up from the estuarine areas to spawn, but they also often lead to reduction in fish numbers and species diversity.

The damming of the Mahanadi has affected fish diversity - from 183 species in 1955 to just 43 in 1992.The situation is grimsays P K Mishra of Orissa's fisheries department. The Farakka barrage in Bihar that came up in 1975 has made a deep impact on the fish catch.Around 98 per cent of thefishery has collapsed after the barragesays Sinha. Similarly, the construction of the Hirakud dam in Orissa has led to a sharp decline in fish catch - from 293,601 metric tonnes in 1996-97 to 234,632 metric tonnes in 2000-01.We catch just half of what we used to in 1950ssays an old fisherfolk of Khunti village, who has given up the occupation.

Moreover, other factors such as water extraction have further worsened the situation. According to V V Sugunan, director, CICFRI, large-scale water abstraction for irrigation and other purposes is responsible for the decline of major carps in the Ganga. Encroachment has also reduced the area of waterbodies and diseases have taken a toll on the fish population in Bihar and Assam. The list of threats is endless. If traditional fisherfolk have to survive against these odds, they need support from ahumanised" system.

Net solutions

Restoring waterbodies and making traditional fisherfolk stakeholders in fisheries development may save this fast disappearing tribe

DESPITE the problems, the solution seems easy. Sample this: "Even if we get half the fish that we used to catch earlier, we can live again," says Dasrath. What Dasrath is hinting at is the restoration of the ecology of the rivers and inland fisheries. According to Dehadrai, the degradation of the inland open water resources has dealt a major blow to the traditional fisherfolk. These resources need to be restored. The polluters must be taken to task.

But given India's poor track record of controlling pollution, quick results will be difficult. With states squabbling over water rights, pollution control boards hand in glove with polluters and implementing agencies in cahoots with the fish mafia, it will not be a smooth sailing for traditional fisherfolk.

Owning up

A major hurdle for monitoring inland water resources is the ownership system. The Indian Fisheries Act came about in 1897, and following Independence, a number of inland water resources were transferred to the government institutions for revenue earning purposes. Now with the panchayats, private contractors and other government agencies are the owners and fishery resources are not common property resources. Being an unorganised sector, there is neither data nor regulation. This has again gone against the traditional fisherfolk. To make matters worse, some experts are losing hope on the riverine systems as a potential capture fishery resource. However, they believe that rivers can be used effectively to conserve fish biodiversity.

Related Content

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding Gopanpally lake pollution, Hyderabad, Telangana, May 1, 2025

- Report by Court Commissioner on Ghazipur landfill and waste to energy plant at the landfill, 29/03/2025

- Joint committee report on crocodile deaths in Rajasthan river, 24/02/2025

- Affidavit by the District Magistrate, Kanpur Dehat, Uttar Pradesh regarding the encroachment and disappearance of the ponds, 15/01/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding pollution of Ashtamudi lake, Kollam district, Kerala, 07/01/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding encroachment of a water body Chandan Polchari, village Gopinathpur, district Puri, Odisha, 05/12/2024