Oasis underneath

IMPATIENT shifting sand dunes and acacia shrubs dot the desolate landscape of Churu district, the gateway to the Thar. Almost invariably, the highest summer temperature is recorded here. Drinking water sources are scarce. The wells are very deep and the water saline. The erratic piped water supply doesn"t even meet domestic requirements. The answer, however, has come from the suffering villagers themselves: kundis, the underwater storage system of rainwater harvested in the monsoon.

IMPATIENT shifting sand dunes and acacia shrubs dot the desolate landscape of Churu district, the gateway to the Thar. Almost invariably, the highest summer temperature is recorded here. Drinking water sources are scarce. The wells are very deep and the water saline. The erratic piped water supply doesn"t even meet domestic requirements. The answer, however, has come from the suffering villagers themselves: kundis, the underwater storage system of rainwater harvested in the monsoon.

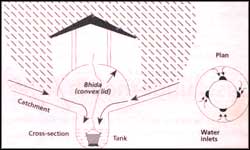

Kundis are covered underground tanks with a saucer shaped artificial catchment area that gently slopes towards the centre. Traditionally, the circular "Rese, catchment area was constructed using a variety of local materials like pond silt, murram, lime, charcoal ash and gravel. Cement, however, is fast replacing these. "Building a good kundi is tough. The soil has to be cleared of vegetation and the catchment area given a smooth gradient of 3 to 4 per cent towards the tank," says Ran Singh, a noted kundi mistri (mason) from Lahsedi village.

On an average, a kundi measuring 5 rn deep, and 2.5 rn in diameter takes 25 days to build and costs about Rs 12,000. After the construction is complete a convex lid, locally called bhida, is placed as a cover. Traditionally, this used to be made from the easily available phog (Calligonum polygonoides) wood, and plastered with mud. Now, either sandstone or ferro-cement is used to make bhidas. The inlets are usually protected by a wire mesh to prevent the water getting contaminated by the debris, birds, reptiles and insects.

Official statistics put Churu"s annual rainfall at 325 mm. Kundis, therefore, have been prevalent all over the district. "Kundis are our treasury in which we store the sweet nectar from the heavens and quench our thirst when all other sources dry up," says Bharat Singh Punia, a lanky farmer from Lahsedi.

Though most kundis are privately owned, some have been built for community purposes. "Outside the village (Lahsedi), a bania (businessperson) from Churu got a big kundi built about 100 years ago," says Nihal Singh. It served the travellers treading the old camel road linking Churu and Hissar. Among the other famous community kundis is the one built in 1957 at Dadrewa, a traditional water-stop for people travelling from Bikaner to Churu. "Not only does it serve about 15 lakh pilgrims who throng the shrine of our warrior saint Gogaji Chauhan in the month of Shrawan (August), but also the travellers round the year," proudly informs Sunga Ram Sharma, its caretaker.

According to one report, businesspeople and rulers have been constructing kundis since the beginning of 17th century for the common folk. In 1607, Raja Sur Singh of Mewar constructed a kundi in the village Vadi Ka Melan. Then, in the sprawling Mehrangarh fort of the "blue city", jodhpur, a huge kundi was constructed by Maharaja Udai Singh in 1759. During the Great Famine of 1895-96, kundis were constructed on a largescale basis, and since then they have spread remarkably fast in western Rajasthan.

Although last year the village was linked to the Rajasthan Canal, and a watertank with a capacity of storing 10,000 litres was constructed in the village, supply remains highly erratic. During the long parched summer the water trickles down once a week, "Then the kundi"s cool water remains the only source to quench our thirst, while the tap water is used to feed cattle," says Chandravati Devi.

Kundi water quenches the cattle as well. A big kundi with a 7 m-deep tank and charcoaJ-based catchment area was built by Sobak Singh in 1957 just outside the Nyangali village on the Churu- Bikaner highway. It had a channel linking a small tank outside the kundi saucer. The water was having poured into the channel so that cattle could drink it from the tank. Presently that channel is damaged, "because we use the nearbysmaller kundi for our cattle, " informs Nanu Singh, Sobak Singh"s son.

In July, the joyful gathering of clouds in the sky kicks off a spurt of cleaning activities to get the kundis ready to receive the blessings from the gods. "No cattle is allowed to graze around the saucer and shoes have to be kept off," says Mahendra Singh of Nyangali. The tank is cleaned and replastered, if needed. Even if it rains moderately in a given season, a good harvest is ensured. With a rainfall as less as 100 to 150 mm, a kundi with an area of 100 sq in could collect about 10,000 litre water.

The Rajasthan Canal has seen the kundis lose some of their past eminence. Many of Nyangali"s kundis lie in disrepair and in Labsedi, only a few have come up during the last 5 years. Yet, because the water supply is too erratic, the villagers h@ve not given up the kundis altogether. "Now we treat it as an alternate source of water," informs Kanwar Pal Singh of Nyangali. But, in Dadrewa, where the water supply is a little more regular, most households don"t have kundis.

Though the government of Rajasthan had started promoting kundis for minor irrigation and drinking water purposes from the early "70s, it has treated kundis as a supplementary source to meet drinking water crises. With 950 villages of Churu having been covered by the government"s water supply scheme, as the government claims, "Kundis can cater only to limited demands," argues R N Arvind, District Collector, Churu.

Last year, the government discontinued the subsidy given to individuals for building kundis for #ieir personal use. But Arvind insists, "People of the district want to continue it and the district administration too favours it." Presently a subsidy is given to panchayats for building kundis for community use through the Jawahar Rojgar Yojana - a programme sponsored by the Central government @tq generate additional employment and create productive community assets in the rural areas. For general water supply the government is bank- ing upon Rajasthan Canal, the Rs 800 crore mega project.

Currently, kundis built by the panchayats function as pyaus (public drinking water outlets), serving water to travellers. Villagers are not allowed to take water for their daily use from these kundis. "I quench the thirst of countless people every day, but I myself have no access to this kundi"s water for my - family," says 65-year-old Mahavir Prasad Sharma of Lahsedi, caretaker of the panchayat"s kundi. Save for occasions like marriages, the common kundi water in Nyangali too is not available to the villagers.

Most kundis being privately owned, the poor have by and large been deprived of this precious commodity - sweet water. "Poor people like me have no use for the kundi. I still depend on the saline water of the village well, and its level has gone so far down that I get blisters on my hands pulling water out of it," laments Dularam of Nyangali. Similarly, Ran Singh, the mason who had started building kundis when he was barely 15, himself doesn"t own any, and depends on the erratic water supply for the drinking water requirements of his family.