`Spare parts` for sale

THERE'S an unanticipated hurdle to the Indian government's Transplantation of Human Organs Bill (THOB), 1992, which allows collection of organs for transplant from bodies of accident victims and "brain-dead" individuals with the permission of their next-of-kin. The government seems not to have realised that, in a backward country like India, will grieving relatives allow doctors to remove organs from the body?

THERE'S an unanticipated hurdle to the Indian government's Transplantation of Human Organs Bill (THOB), 1992, which allows collection of organs for transplant from bodies of accident victims and "brain-dead" individuals with the permission of their next-of-kin. The government seems not to have realised that, in a backward country like India, will grieving relatives allow doctors to remove organs from the body?

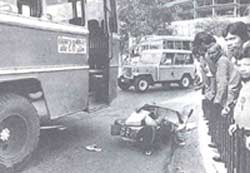

It seems unlikely unless a massive and sustained publicity campaign convinces people that it's noble to donate their body organs after death, as the organs can help save somebody else's life. The Indian government has made no effort to motivate people. It's quite possible that THOB may not improve the availability of hearts and kidneys -- the organs most commonly transplanted in India. It's a pity because accidental deaths kill 600,000 Indians every year. Transplant surgeons say that if the organs of even a small percentage of these victims could be harvested, the shortage of body organs for transplant could be reduced dramatically.

In India, an estimated 80,000 people suffer renal failure every year, whereas kidney transplants number only about 2,000. A majority of the recipients buy kidneys from impoverished people for anything between Rs 30,000 to Rs 60,000. The transactions are so routine that advertisements for kidneys appear in leading daily.

THOB bans trading in body organs and recommends seven years' imprisonment for violators. But as things stand, the bill will only drive the trade underground. Somebody or the other will continue to supply organs for money. The trade can end only when kidneys for transplant become legally available from bodies of the recently dead.

Unlike India, the British government recently spent L1.5 million, urging people with driving licences to carry donor cards authorising the removal of their body organs in case of death in an accident. Twenty-two per cent of British motorists already carry these cards, but the latest campaign intends to motivate more people to do the same. In fact, British hospitals are planning to set up a national computerised register so that they can check within minutes of an accident whether the victims wanted to donate their organs.

Isn't it time India woke up to the revolution in "spare-parts" surgery? Leave alone transplanting eyes, kidneys, bones, bone marrow, ear drums, liver, pancreas, lungs and hearts, surgeons in the West today think even a knee joint, hip, scalp or tongue can be replaced.

Our government should follow the example of Austria, Denmark, France and Switzerland, all of which permit organ removal under the qualification of "presumed consent". This allows doctors to extract an organ from an accident victim unless a relative objects.

Sever shortage The shortage of kidneys in India is severe, as can be evidenced by this incident related by Vinod K Thukral, who teaches in a US university. Thukral said he met a Saudi surgeon who told him of potential organ-sellers lining up in front of a Bombay hospital, hoping to be selected by kidney buyers who inspect these poor people like cattle, choosing the healthiest.

Another damning indictment came last March from a UN report, in which Vitit Mutarbhorn, special investigator on children's rights, said India has the "dubious honour" of being the country in which the largest number of clandestine organ transplants are performed using children's organs.

No amount of legislation can curb this clandestine trade of body organs. The trade takes place so openly that Madras even has a suburb called Kidneyyakkam. In the US, where the buying and selling of human organs is banned, fewer than 1 per cent of total kidney transplants take place between unrelated living people.