INDEPENDENCE DAY SPECIAL

This mobile version does not have the slideshow switch

INDEPENDENCE DAY SPECIAL | ICONS OF FREEDOM

HOW TO NAVIGATE

1. SWITCH VIEW

2. USE ARROWS

3. DRAG SLIDERS

1. Switch view: Click on the icon on top right of each page to view all features;

select the feature you would like to read by clicking on it

2. Use arrows: Click on the arrow below each page to read full article or use keyboard arrow buttons

3. Drag sliders: Use mouse to drag the slide to reach the next article

select the feature you would like to read by clicking on it

2. Use arrows: Click on the arrow below each page to read full article or use keyboard arrow buttons

3. Drag sliders: Use mouse to drag the slide to reach the next article

Icons of freedom

Animal fat, salt, minor forest produce, indigo and khadi are icons evoked by

reference to the freedom movement.

How do they fare today

Salt workers are neglected

From British monopoly to industrial dominance

Livery of freedom

fails to bring liberty to the poor

Weavers and spinners engaged in Khadi production earn less than

daily wagers under rural employment scheme

Independence's major minor players

The colonial state stamped itself over forest; independent Indian

state continues to do so

Indigo stages a comeback

The colonial state stamped itself over forest; independent

Indian state continues to do so

Animal fat has crept into several products

It's not just an issue of upsetting vegetarian sentiments,

animal fats are linked to toxins

Icons of freedom

Salt workers are neglected

From British monopoly to industrial dominance

Kaushik Dasgupta

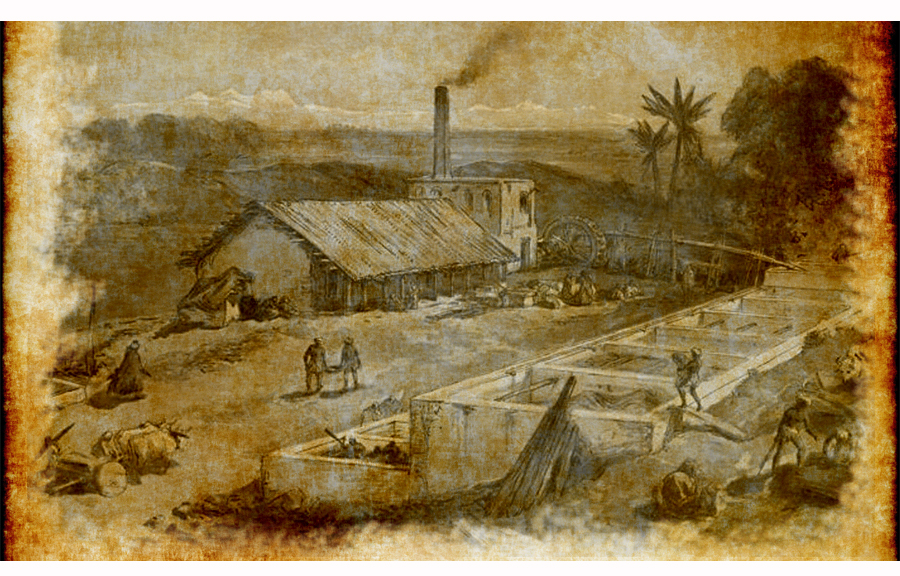

In 1790, the East India Company requested permission to buy all salt produced in Orissa. Raghuji Bhonsle, the Maratha governor of Orissa, refused. Bhonsle realised that the British were trying to eliminate salt produced in Orissa as a prelude to selling to British salt at an artificially high price

.jpg) The East India Company retorted by banning Orissa salt in Bengal, which it controlled. But the Bengal-Orissa border was a thick jungle, difficult to patrol and well-organised bands of salt smugglers took advantage of the ban. Inexpensive salt from Orissa flooded Bengal and British salt still could not compete. In 1803, under the ruse of fighting contraband salt, the East India Company annexed Orissa and year later, salt became a British monopoly. Private sale of salt was prohibited. In 10 years, it became illegal for salt to be manufactured by anyone other than the British government.

The East India Company retorted by banning Orissa salt in Bengal, which it controlled. But the Bengal-Orissa border was a thick jungle, difficult to patrol and well-organised bands of salt smugglers took advantage of the ban. Inexpensive salt from Orissa flooded Bengal and British salt still could not compete. In 1803, under the ruse of fighting contraband salt, the East India Company annexed Orissa and year later, salt became a British monopoly. Private sale of salt was prohibited. In 10 years, it became illegal for salt to be manufactured by anyone other than the British government.

Some Malangis, or salt workers in Orissa, continued manufacturing salt illegally. But by 1815, hundreds were arrested. In 1817, the Malangis, revolted, destroying British salt works and salt offices. The Company came down on the rebellion with a heavy hand.

.jpg)

But salt smuggling continued even though the Company had custom checkpoints in large parts of the country. In 1840, the Company constructed a 14-foot high, 12 feet thick thorn hedge along the western side of Bengal to stop salt-smuggling. After the 1857 revolt, the British government took over from the Company, the hedge, now a spiky gnarl of prickly pear, acacia and bamboo, expanded 4,000 kms from the Himalaya to Orissa. By 1870, this custom line dedicated to enforcing British monoploy over salt employed more than 1,000 men.

But despite the malangi rebellion in Orissa and at a few other places, salt remained largely out of the agenda of the national movement. Till 1929. This was when Mahatma Gandhi mooted the idea of a salt-satyagraha at the Lahore Session of the Indian National Congress. Gandhi argued the salt-policy exemplified British misrule.

.jpg)

On 12 March 1930, Gandhi and 78 of his followers left the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad. When they reached the sea at Dandi 24 days later, the band of protestors had grown by thousands. On 5 April, the Mahatma waded out towards the beach to a point where a clump of salt evaporated by the sun was cracking. He bent down and picked up a chunk, and in broke the British salt law.

Thousands of kilometres away on the eastern coast in Orissa, people did likewise. A year later people living on the coast were allowed to make salt—though for their use only.

After independence salt-making was organised around cooperatives, most of which failed. India is the third largest Salt producing Country in the World after China and USA with Global annual production being about 230 million tones.India is the third largest salt producing Country in the World after China and USA producing about 22 million tonnes annually. With a market share of 64 per cent in the branded salt market, Tata Salt is the leading player, followed by Hindustan Unilever's Annapurna, Nirma's Shudh Salt and ITC's Aashirvaad Salt.

The government is supposed to look after the interests of salt-workers through the salt-commisiorate. Mark Kurlansky, the author of Salt, A World History writes, “Across the river from Gandhi's Ashram in Gujarat's salt-commisiorate is seen as upholding the interest of traders rather than workers.”

The salt making Agarias of Gujarat face an uncertain future. A 2006 report of a Union ministry of environment and forests-World Bank project, Biodiversity Conservation and Rural Livelihood Improvement, notes that nearly 60 per cent Agarias live below the poverty line.Their livelihood has been under threat ever since the Little Rann of Kutch (the Rann is divided into the Little Rann and the Great Rann) was notified as a wildlife sanctuary in 1973 to protect the wild ass. In 2006, the salt workers were served eviction notices.

Livery of freedom fails to bring liberty to the poor

Weavers and spinners engaged in Khadi production earn less than daily wagers under rural employment scheme

Aruna P Sharma

Khadi, the coarse cotton fabric woven by hand and made from handspun yarn, was worn by poor peasants and artisans in pre-industrial period. During India's freedom movement Mahatma Gandhi turned the poor man's charkha or spinning wheel and khadi into symbols of self reliance, discipline and means to attain swaraj or self rule.

The fabric could be made at home with homespun yarn obtained from locally grown cotton. Production of the cloth was in decline when Gandhi saw in it the potential to provide livelihood to the poor as well as freedom from the mill cloth imported from England, which was blamed by many for the decline of Indian handloom textiles.

Gandhi started promoting Khadi in 1918, initially as a means to provide relief to the poor of the country. He gradually built it up into a movement to give expression to the spirit of nationhood and push for boycott of foreign goods. It was at the Nagpur session in 1920 that the Indian National Congress decided to encourage Khadi. It was central to the non-cooperation movement in 1920-21. The first Khadi Production Centre was established at Katiawad, Gujarat. India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, referred to the fabric as "The livery of freedom".

In 1934-35 Gandhi expanded the idea from helping the poor individual to self-reliance of whole villages through Khadi Village Industries (KVI). In 1942-43 he had sessions with workers groups and village organizers to re-organize the whole programme on a country-wide scale.

"I have not hesitated to say, and I make bold to repeat, that there is no swaraj for the millions, for the hungry and the naked and for the millions of illiterate women without khadi. Habitual use of khadi is a sign that the wearer identifies himself with the poorest in the land, and has patriotism and self-sacrifice enough in him to wear khadi even though it may not be so soft or elegant in appearance as foreign fineries, nor so cheap," said Gandhi in an article in Harijan in 1940.

Post Independence, the government of India set up the Khadi Village Industries Commission (KVIC) to support industry units, which included financing, ensuring procurement of raw material, technology development and marketing of products.

The humble cloth has come a long way since the Freedom Movement and it is promoted by well-known designers and worn by celebrities as a fashion statement. But has Independence brought liberty to the humble weavers and spinners of Khadi yarn and fabric?

A 2011 study published by Pesala Busenna and A Amarender Reddy in the Journal of Rural Development shows that the per capita earnings of spinners, weavers and other workers in the Khadi sector is an average Rs 3,203. Spinners get paid the least, while earnings of silk weavers are marginally better at Rs 8,683 per annum. The report also shows that the sector has only witnessed marginal employment growth.

The report also mentions decline in Khadi products in recent years because of inflation, escalation of raw material value and shortage of working capital.

What's more, the withdrawal of the rebate scheme on Khadi products four years ago has made the cloth more expensive and less attractive for common people.

Noted Gandhian scholar and director of Sabarmati Ashram Preservation Memorial Trust, Tridip Suhrud, stresses on the importance of seeing Khadi as a mode of livelihood rather than a symbol of freedom to improve the condition of the rural poor

"We need to distinguish between Khadi as a symbol and Khadi as a mode of life and livelihood. The National movement adopted Khadi as a symbol but not many in the country saw the imeprative of Khadi as a mode of livelihood. The creation of All India Weavers Association and All India Spinners Association under the leadership of M K Gandhi and J C Kumarappa was a defining moment in our struggle against poverty and hunger,” he says.

“Today, Khadi has declined both as a symbol and as a mode of livelihood. A new aesthetic has also emerged, which gives a marginal place to Khadi. Organisational and technological innovations are required to make spinning and weaving a viable mode of earning livelihood," he adds.

Recently, the BJP-led NDA government at the Centre dissolved KVIC. It said the organisation will be made more efficient and provide livelihood opportunities to the poor, something the previous Congress-led UPA government had also promised when it came to power in 2004. Whether this government delivers on its promise is something that remains to be seen.

See also Organic cotton production and consumption should become a mass movement

Handloom threatened

Hanging by a thread

The Baigas and their weavers

Handloom is haute

Chirala Saree weavers losing out to computer-aided designs

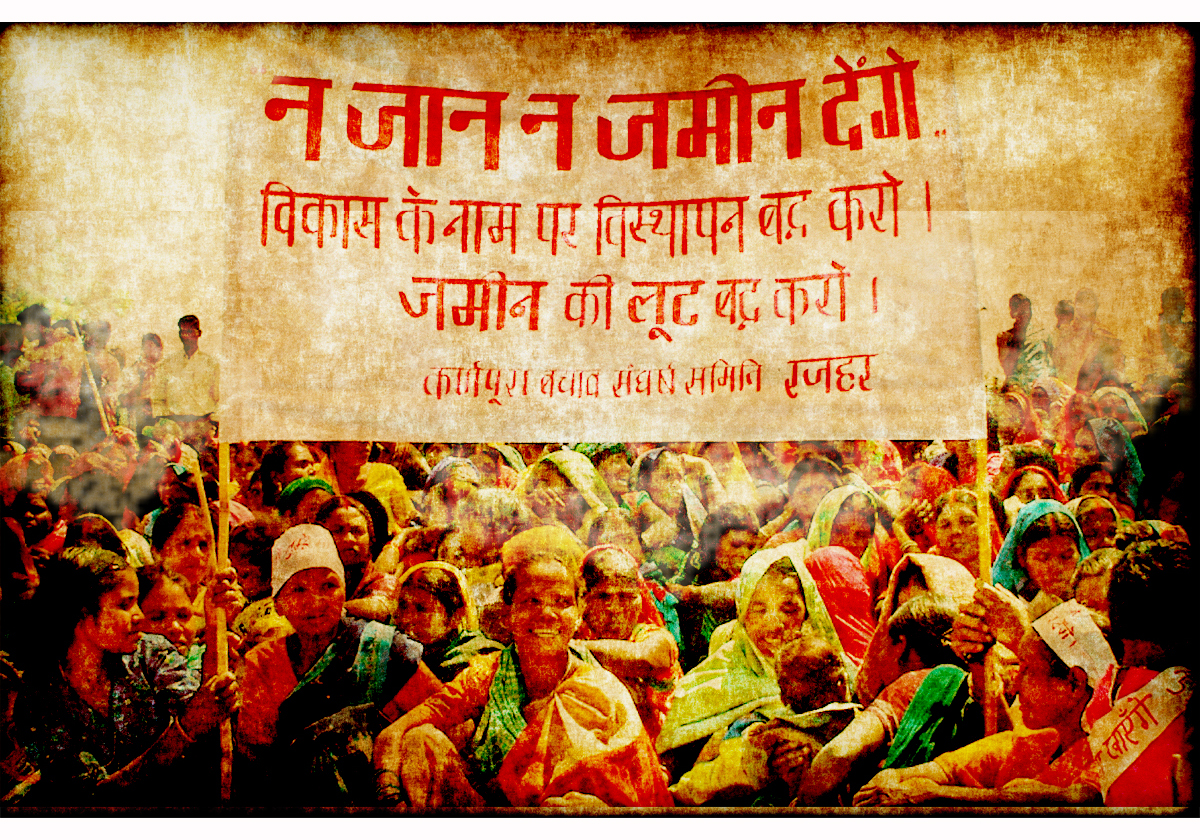

Independence's major minor players

The colonial state stamped itself over forest; independent Indian state continues to do so

Richard Mahapatra

Minor forest produces were a major instrument to control the spread of independence war.  Little known or disseminated in contemporary history, Sepoy Mutiny, the first war of independence, led to centralisation of India's forest forests. At the core of this regime change was the access to minor forest produces, key source of food security then, and now as well. Thus, MFPs enjoy no less iconic status then any other such

Little known or disseminated in contemporary history, Sepoy Mutiny, the first war of independence, led to centralisation of India's forest forests. At the core of this regime change was the access to minor forest produces, key source of food security then, and now as well. Thus, MFPs enjoy no less iconic status then any other such

In the aftermath of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857, the East India company worked on a very regressive plan to stem the fast spreading movement for freedom. Forests became the new stage for this governance conspiracy that more or less still continues. Tribal residents of forests gave shelters to rebels in face of the company's crackdown. How did the officials react?

In 1860, company administration just centralised the access, use and trade of MFPs. These include produces like tendu patta, uncultivated foods used round the year and also bamboo. This set in the process for further centralisation of forest management. Tribals' all access, rights and privileges over forest and forest produces got curtailed giving the company absolute power over them. It was a severe food crisis period for the tribals.

In 1864, the Imperial Forest Department came into existence that consolidated government control over forests, forest produces and the livelihoods of tribals. At the same time, across the country there was a parallel built up of movements against this. Such movements starting from the Chotanagpur Plateau to Srikakulam, widely known as tribal struggles but never seen as a natural part of the larger freedom movement, arguably became India's most local and organised freedom movements using rights over forests.

For more than 150 years, the control over access to MFPs remained. The colonial forest department mutated further notwithstanding the Independence. The MFPs went through many bureaucratic definition changes to further strengthen the forest department control over them.

In 2006 came the Forest Rights Act: the first legislation that not only started tribal habitation settlement in forest areas but also gave them the right over the MFPs. It is the first legislation that 'defined' MFPs that include the bamboo and tendu, two lucrative sources of revenue for forest departments.

Not precisely. It took more than four years for the law to liberate the MFPs from the clutches of forest officials. In 2010, a few villages in Maharashtra's Gadchiroli district finally became the first ones to assert the right over MFPs using this law and they were granted it too. Soon, the forest department put a spanner: bamboo can't be a MFP or it can't be transported out of village without forest department's permission or a transit pass. It reminded the same governance conspiracy that the East India Company did with the tribals in 1860.

'On April 27, 2011, the then environment minister Jairam Ramesh went to Mendha-Lekha village in Gadchiroli to hand over the right over bamboo to the community fighting for it for years. The FRA saw its first intent to come true: undoing the historic injustice. But the freedom movement started in 1857 in Indian forests still continue as many communities still don't have access to the MFPs.

Indigo stages a comeback

Indigo, which was the cause for Mahatma Gandhi's famous Champaran Satyagraha, is now witnessing a global revival

Richard Mahapatra

Colour is always a political subject. Going by this, Mahatma Gandhi's satyagraha can be termed as indigo in colour. Gandhi led his first Satyagraha in Champaran district of Bihar and the Kheda district of Gujarat in 1916 and 1918 respectively. This revolved around the plight of indigo farmers who were up against the British and local indigo planters. This also witnessed the first instances of people calling Gandhi as Bapu.

Colour is always a political subject. Going by this, Mahatma Gandhi's satyagraha can be termed as indigo in colour. Gandhi led his first Satyagraha in Champaran district of Bihar and the Kheda district of Gujarat in 1916 and 1918 respectively. This revolved around the plight of indigo farmers who were up against the British and local indigo planters. This also witnessed the first instances of people calling Gandhi as Bapu.

In Champaran thousands of marginal farmers and landless were forced to grow indigo replacing their staple food crops. Indigo plantation was like minting money due to a boom in demand in England. Starting from undivided Bengal to Bihar, British created a forced cropping regime to produce more indigo. The local zamindars conspired with them.

In 1914, farmers in Pipra revolted against this tyranny. They refused to take up indigo plantation. A famine had already ravaged their lives as less and less areas yielded foodgrains. What's more, the British imposed a new tax that took away more earning from farmers, who in any case received very little revenue from indigo farming. Raj Kumar Shukla, an indigo cultivator, persuaded Mahatma Gandhi to go to Champaran to start the Satyagraha.

However, Gandhi didn't ask farmers to demand independence, but freedom from the taxing economic regime.

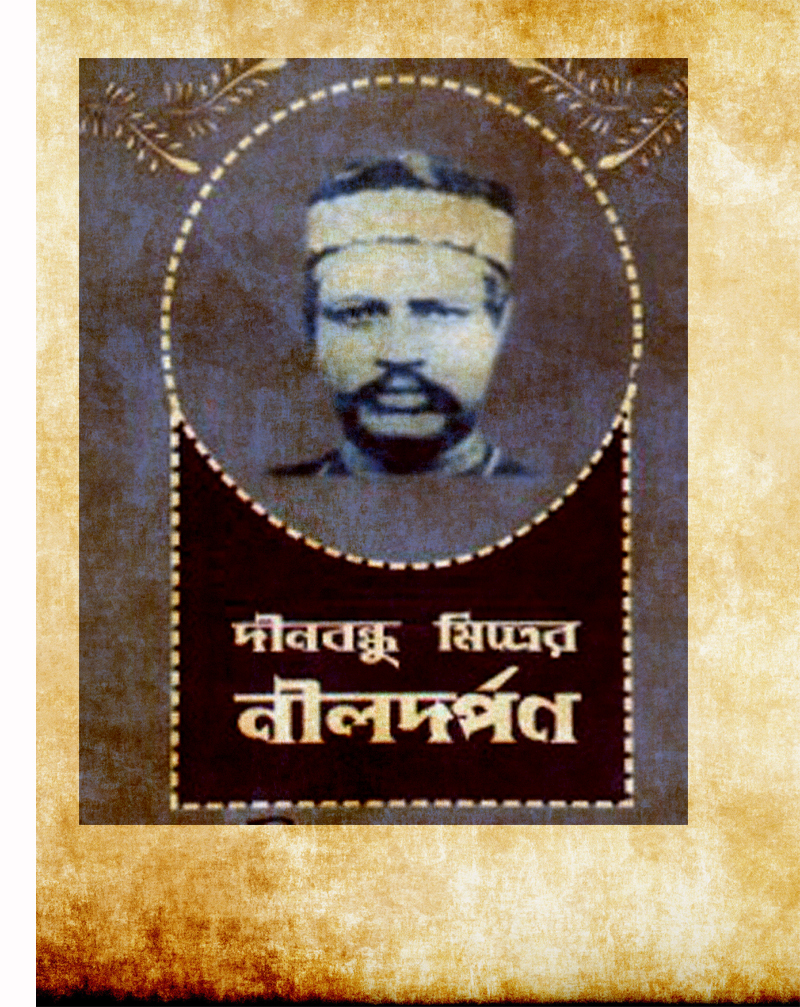

Much earlier, the undivided Bengal already was a stage for a revolt against the British, again fuelled by the exploitation of indigo farmers. The Bengali novel, Nildarpan, by Dinabandhu Mitra captures these revolts and the plight of indigo farmers vividly. This novel also stirred the thoughts of many a European mind, thus triggering a public debate there.

But by 1910s, invention of a synthetic alternative to natural indigo changed the landscape, both in politics and economics. In 1907, Bayer Hoechst, a German company that still exists, invented a chemical way to produce synthetic indigo. Within a few years the price of natural indigo crashed and the demand for synthetic indigo spurted northwards. Though the iconic plant was losing the economic battle, its contribution to freedom struggle was already made.

Indigo farming has almost vanished from India now, but its bitter memories still haunt the states of West Bengal, Bihar and Gujarat. But the icon of this movement, the indigo, seems to be reviving across the globe. More so in India's neighbourhood—Bangladesh and Pakistan. A few villages in Nagaland and Bihar are reviving indigo cultivation, but not to remember the tyranny that involved indigo farming but to fix the nitrogen deficit in their soil. In European cities, natural Indigo dye has started creating the buzz in fashion corridors. As a few fashion writers write: “A forgotten revolution comes back to life in the corridors of...”.

Animal fat has crept into several products

It's not just an issue of upsetting vegetarian sentiments, animal fats are linked to toxins

Vibha Varshney

Many consider the 1857 the beginning of the freedom struggle in India. The seeds of the revolt were sown when the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle was given to the soldiers of the East India Company in Meerut. To load the gun, the sepoy had to bite the cartridge by his teeth. The soldiers came to know that the paper cartridges were greased with animal fat – either lard (pork fat) or tallow (cow fat). From then on, neither the Muslims nor the Hindus wanted to touch the cartridges for religious reasons.

But 156 years after the first war of independence, animal fat has crept into several products. We not only eat it directly but we even grow our food with it. We do not just touch it occasionally by accident but deliberately slather it over our bodies every day.

Victories for those who want to abjure animal fat are rare. In 2002 fast food giant McDonald's Corporation had to pay $10 million to vegetarian and religious groups for misleading them into believing that their French fries were fit for vegetarians. In 1990, the company had claimed that it had switched to vegetable oil in its fries. But it seems that this was mainly to control levels of cholesterol and the company continued to use small amounts of beef flavouring. As they failed to inform the consumer about this, a Harish Bharti, an Indian lawyer based in Seattle slapped a case on them. But that was an one-off incident.

Tallow has made its way indirectly into our food cycle as an ingredient of a commonly used herbicides. US based multinational Monsanto's Round Up has a chemical, Polyethoxylated tallow amine, which works as a surfactant and increases the uptake of the active ingredient, glyphosate, by the plant. This is a broad-spectrum herbicide which is the world’s largest selling herbicide. Since 1974, when it was introduced, use of glyphosate has increased rapidly, especially after the introduction of genetically modified glyphosate-tolerant crops.

A 1997 review by the US Forest Service says "presumably, the Roundup surfactant is a derivative of tallow, a complex mixture of fat from the fatty tissue of cattle or sheep."

But here it's not just a matter of eating consuming non-vegetarian: the chemical is extremely harmful. A November 2013 study showed that this chemical actually increased the toxicity of the herbicide. The team which included Gilles-Eric Séralini, a renowned anti GM activist from France’s University of Caen, found this ingredient was toxic to human cells and was a threat to human health. The industry considers this compound to be inert but it was actually more toxic than the active ingredient.

Many types of animal fats now part of an Indians life. The risk of finding animal fats in food is quite high in imported products such as cookies and crackers, and tortillas. You can come in contact with lard and tallow in waxed paper, margarine, soaps, crayons and candles. Worcestershire sauce, Caesar salad dressing, pizza topping, Greek salads have anchovies (fish). Marshmallows, yogurt, frosted cereals, and some desserts have gelatin from bones, cartilage, tendons, and skin of animals.

Even personal care products like soaps could contain animal fats. Glycerine and glycerol which are commonly used in soaps can be either synthetic or derived from plants and animals (tallow). A 2010 report from The Vegetarian Resource Group found that in the case of cosmetics and in bath and body products, the source of glycerine is rarely given clearly. These chemical are also used in toothpastes, mouthwashes, chewing gum, ointments, pharmaceutical formulations, cough syrups, cosmetics such as perfumes and lotions, skin care products, shaving cream and hair care products.

In today’s world, the cartridge most likely would have come with a red dot on it. This is the FSSAI’s way of telling the vegetarian that the product contains a product derived from animals. The labelling came up in 2011 after the Food safety and standards (packaging and labelling) regulation in was put in place in accordance to the Food safety and standards (packaging and labelling) act of 2006. But the rules are only for food leaving an array of avenues open for exposure. Would Mangal Pandey have found this acceptable? Maybe, it is time for another fight for independence: against the multitude of toxins in our food – pesticides for one.