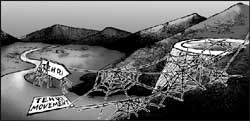

Tehri: is it curtains?

The closure of tunnels T3 and T4 comes even as a vast majority of people displaced remain to be rehabilitatedeven as recommendations of the Union government appointed Hanumantha Rao Committee remain to beimplementedeven as the Prime Minister appointed Murli Manohar Joshi committee is yet to submit its report and even as a number of petitions remain pending in the Supreme Court. Of the many questions left unanswered by this abrupt movethe issues relating to relief and rehabitilation (R&R) seem to be of immediate concern.

The closure of tunnels T3 and T4 comes even as a vast majority of people displaced remain to be rehabilitatedeven as recommendations of the Union government appointed Hanumantha Rao Committee remain to beimplementedeven as the Prime Minister appointed Murli Manohar Joshi committee is yet to submit its report and even as a number of petitions remain pending in the Supreme Court. Of the many questions left unanswered by this abrupt movethe issues relating to relief and rehabitilation (R&R) seem to be of immediate concern.

As a report by South Asia Network on DamsRivers and People released in November 2001 showed even 25 years after construction work beganno accurate data on the number of people affected is available. Large number of these people arein factnot even included in the R&R package. The land available is of questionable quality or already belongs to other communities. And over 70 per cent of the rural families and over 80 per cent of urban affected families are yet to receive basic allotment of resettlement benefits.

Amazinglythe annual reports of Union power ministry for the years 1997-98 to 2000-01 all say that R&R for 98.5 per cent of phase I rural affected families have been completed while the ones for the years 1994-95 to 1996-97 claim that all these have already been completed. Are we to believe that between 1994 and 2001not only was there no progress in R&Rin actualitythe claims of resettlement achievement had to be watered down? In yet another flip flopon December 252001advertisements in most dailies of Delhi claimed that 13 per cent of phase I eligible rural families and full 45 per cent of urban displaced families were yet to be resettled.

Now if that was the casewhy were the tunnels T3 and T4 closed as such closure was bound to lead to irreversible submergence of the Tehri town and with it the submergence of the basic infrastructure facilities for the Tehri residents? Was it not clearly a threateningrepressive measure for the residents of submergence area that they better accept whatever is offered to them and vacate the submergence zone? As if to prove such fears righton January 62002the police reportedly beat up hundreds of peacefully demonstrating people and arrested 24 of them. In the Tehri townthe indefinite dharna by the affected people is going on now for over a month.

In addition to the protest actions on R&R-related issuesprotests inthe context of Tehri dam have been coming up at a number of places in recent past.

On August 4 2001over a hundred womenmen and children gathered in the forests of Advaniin the Henwalghati region of Tehri Garhwal to protest against cutting of the famed Chipko forests for the high tension transmission lines being built by the Power Grid Corporation to evacuate power from Tehri Dam.

The agitated locals started a movement from October 152001in protest when forest department started allocating land titles in the Pathri protected area in Haridwar forest ranges to people from the Tehri submergence area. The localswho have been staying in the area since 1930s and who created the plantationsare still landless.

Earlier in June 2001following serious corruption charges against Tehri Hydro Development Corporation officials and J P Associatesthe main contractor of the damwhen the officials tried to stall the investigations by Central Bureau of Investigationlocal people and workers had protested saying the officers were attempting to hide their misdeeds.

Meanwhileit may be remembered that following the massive Kutch Earthquake of January 2001Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee had declared that there is a need to review the projects like Tehri coming up in known seismic active areas. That was one of the mandates of the multi disciplinary 11-member committee appointed by the Prime Minister on April 102001under the chairmanship of no less a person than Union human resource development minister Murli Manohar Joshi. That committee was supposed to give its report in four weeks. On November 302001over seven months laterthe committee was yet to finalise its report when tunnels T3 and T4 of the Tehri dam were closedtaking the project closer to irreversible situation as far as the seismic design is concerned. This sequence of events raises many questions. Were the authorities playing games with the people being risked by the Tehri dam and the rest of the nation? Was the Joshi committee expected to act as a rubberstamp of the government decisions? What happened to the promise of the Prime Minister to review the seismic aspects of the Tehri project?

As far as the cost of power is concernedminimum per unit cost of power from the Tehri Project would be Rs. 4.52 at current prices. In the Northern grid stateswhere this power is supposed to be consumedthis is higher than the cost and the price of power in all the states by a wide margin of 50-100 per cent. This also nails the lie of hydropower being cheap. Who will pay even the economic cost of this power if and when the project is finally completed and power starts getting generated?

Since the immediate impact of closure of the two tunnels was irreversible submergence and displacement of thousands of people yet to be resettledit was natural that the issues that came to fore during this event were mainly those related to R&R. But that does not mean that the other crucial issues raised by the Tehri struggle will be bulldozed or submerged under tunnels T3 and T4. In the Supreme Court case and even outsidethese issues are bound to come up repeatedly in days to come. The larger movement for more participatoryequitablesustainable and sound water and energy resource development and management will of course continue to raise these issues.

Himanshu Thakkar is coordinatorSouth Asia Network on DamsRivers and People (SANDRP)

It is one suspectsinsufficiently appreciated that the Tehri dam project violates all procedural norms underwritten by the governmenthaving been turned downnot once but twiceby its appointed environment clearance committeees. Not only does this damlocated in a high-risk seismic zonepose unacceptable dangers to all those living downstreamits active project life is likely to be much shorter than officially claimedgiven the high rates of siltation associated with Himalayan rivers. Of courselike all large dam projectsit inundates valuable forest and farming land and displaces people in over 100 villages as also Tehri town. These 'facts' are well-known and documented in official reportsindependent studies as well as the testimonies of senior scientists. Ifneverthelessthe government ignored all evidence and is now set to inaugurate another temple of modern Indiait only goes to show thatrational arguments cut little ice in the murky environs of our decision-making apparatus.

More intriguing is why the protest against the dam failed to acquire a significant social presenceboth in the local and national domains. Unlike Sardar Sarovar on the Narmada which became a cause celebrethe Tehri protest never quite captured the imagination of the growing tribe of enviromentalists and green journaliststhis despite the case against the dam standing on firmer ground than most others. It is unlikely that those most directly affected by the project were ever conviced that the dam would bring them benefits - be it electricitydrinking water or a boom to the local economy. Equallyit is difficult to believe that they were swayed by the allure of compensation and resettlementparticularly given the officialdom's dismal record on this count. So why their relative apathy? One suspects that a key problem with the anti-Tehri dam movement has been its highly centralised characterrelying inordinately on Sunderlal Bahuguna's charisma. As a towering personality of the regionit is he who gave shape to the protest. And given his statureit was never easy forothers to join in except on his termsgiven particularly his never-quite-hidden uneasiness with outsiders. Somore than building up local networks of residence or seeking alliances with outside researchersscientistsactivists (though each of these at different points of time did play a role)what will be more remembered are Bahuguna's long fasts to force a rethink of theproject. These did win him some time but were insufficient to stop the dam construction.

Even more disconcertingparticularly in the 1990swas the use of a religious idiom to buttress his casehow a 'holy' river was being desecrated by development intervention. The subsequent involvementif not takeoverof the struggle by Vishwa Hindu Parishad mahants and religious leaderstheir intemperate speechfurther muddied the waters and alienated both secular activists and minority opinionBut more than the aboveit is probably the aftermath of the Chipko strugglea movement with which Bahuguna was intimately associatedthat played a crucial role. One implication of the environmental legislation that followed Chipko was that the tiniest developmental intervention in the hills required prior clearance from the Union government. Little surpriseChipkomore so its glorificationcame to be perceived as a conspiracy of city-based greens to foreground nature over peopleenvironment over livelihoods. Locals now complain that they now suffer from two kinds of terrorism - development and environment. This was a major impulse behind the struggle for a separate hill state - a struggle in which Bahugunasurprisingly enoughplayed no role.

It is so far unclear what role these different processes had in defining the contours of the strugglein particular the construction of local apathy. Sustaining protests over long periods is never easy. And each 'failure' only contributes to deepening the despondency among affected people. By no means do they support what is being done to them; just that they are sullenresigned and apathetic. The issues raised by environmental strugglesincluding against the Tehri dam remain much too important to be frittered away. This is why protest movements bear a responsibility greater than what their leaderships may realise.

Harsh Sethi is the consulting editor of Delhi-based magazine Seminar

Considering the story of Tehri is spread in the time span of more than three decades and revolves around the future of more than 1000people as well as of deciding the pattern of development in thefragile Himalayan regiona mere whimper of protest at the time of its submergence seems ironical.

At the time of construction of the controversial dam in 1978there was a spate of protestsstarting with thesetting up of the Tehri Bandh Virodhi Sangharsh Samiti under the chairmanship of V D Saklani. When the anti-dam sentiment reached its peak during the first hunger strike by Sunderlal Bahuguna in 1992it was a time when not only the activistsresidents of Tehri and neighbouring villagesbut people from other parts of Uttaranchal and the rest of the country participated in the movement. The campaign at this time also had a strong scientific and institutional backing.

For the next five years no decision came from the Union or state governments and the construction work continued. Whenever it stoppedit was mostly due to lack of funds. The symbolic halts were more visible in the media. Once the hunger strikes failed to influence the insensitive governmentand most villagers compensated with money or landthe movement started losing momentum. The death of Saklani and the withdrawal of some key activists further weakened the initiative which gradaually came to be associated solely with Bahuguna and his handful of supporters.

It must be noted that no movement is supported by all in any region or country at any given time. Tehri Dam project had many visible and invisible supporters not only inpolitical partiesthe government and the bureaucracy but also among the local people. The problem was that no political party was ready to frankly discuss the positive and negative aspects of the Dam. The project slowly became a 'Kamdhenu' (the mythical cow of plenty) for all - contractorstransporterspoliticiansbusinessmenjournaliststhe industry people and the locals. Everywhere there was euphoria about its probable consequences. In fact many people in Tehri townin the surrounding villages and the absentee landlords ofthe submersion area were among the strong supporters of the Tehri Dam projectas the compensation in hand and the dream of settling near Dehra Dun made them blind.

The reason whyin the last decadethe anti-Tehri Dam movement was not able to sustain itself even after its being termed as Himalaya Bachao Andolan (Save Himalaya Movement) by its leaders is because it was never clear from whom they wanted to save the Himalayaswhy and how. Laterthe Tehri issue only emerged when Bahuguna started or broke his hunger strikes or talked to press. Naturally the movement got marginalized and the national and international support withered away.

Todaythe larger environmental and developmental issues have gone in the background. Nobody is bothered about the seismicitysiltationenvironmental impactreservoir-induced seismicity (RIS)catchment area treatment and the peak ground acceleration (PGA). These issues are very crucial and very much in existence. The submergence of some lower parts of Tehri town is not the end of an ideain which there is still a dream of using the hydro-potential of the Himalayan rivers without making large dams like Tehri. Social silence cannot always be termed as defeat. The study of the social movements of this region suggests that the people will evolve a new model of fighting with state and its own contradictions. But for this we have to evolve a new culture of protests and also the art of transforming a movement into political creativity. It must be also understood that the out-migration for last hundred years has made people of Uttaranchal careless and insensitive about their roots. They can leave their mountain homelandpastureforest and culture for just a house in Tarai- Bhabhar and Dun areas or in the plains anywhere. This cause must be properly analysed and understood.

Shekhar Pathak is the editor of mountain journal PAHAR