Amnesty portrays India`s warts in detail

IN DAYS long gone, the bearer of bad tidings was usually put to death unceremoniously. In today's more civilised times, we in the Third World prefer to vilify such messengers as biased agents of neo-imperialists, who never hesitate to point out the mote in our eyes while remaining blissfully oblivious to the beam in their own. For this reason alone, Amnesty International's latest report on India's human rights record is sure to set "patriotic" Indian hearts reverberating to the drumbeat of disapproval that the government has already sounded loudly.

IN DAYS long gone, the bearer of bad tidings was usually put to death unceremoniously. In today's more civilised times, we in the Third World prefer to vilify such messengers as biased agents of neo-imperialists, who never hesitate to point out the mote in our eyes while remaining blissfully oblivious to the beam in their own. For this reason alone, Amnesty International's latest report on India's human rights record is sure to set "patriotic" Indian hearts reverberating to the drumbeat of disapproval that the government has already sounded loudly.

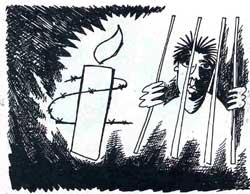

But what other reaction could Amnesty, a worldwide group whose membership includes Indians and whose professed concern is for the so-called prisoner of conscience everywhere, have expected to its meticulous and comprehensive documentation of 459 cases of Indian men, women and even children dying in police custody between 1985 and 1992? Does Amnesty expect any government -- democratically elected or otherwise -- to acquiesce gracefully to a report that is essentially an indictment of its police and army, the enforcing arm of civil authority?

No human being enjoys being portrayed with every wart, wen and wrinkle in place. Much less does a country -- any country -- relish having its shortcomings spotlighted. In the preface to its report on India, Amnesty secretary general Ian Martin insists his organisation "is working universally" to end custodial violence wherever it is uncovered. But this assertion of impartiality only means antagonising each of the countries against whom Amnesty makes out a case. To expect self-enforced reform from a government twitching under an Amnesty indictment is to ascribe maturity to that government, overlooking the probability that a government with such maturity would never allow its law enforcement agencies to run amuck in the first place.

Amnesty's listing of 459 custodial deaths, its description of various methods of torture and mayhem, its examination of why custodial violence occurs and its 10-point programme to combat this evil make for depressing and turgid reading. But they are much too detailed to support even a hint of exaggeration. However, listing custodial deaths in their hundreds does not make Amnesty's case against Indian authorities any weightier. Nor can the apologist for India reduce the 459 cases to a percentage of the total population and then contend Amnesty's case is insignificant.

In the end, if anything positive is to accrue to India from Amnesty's painstaking efforts, it will require that the government concerns itself with the news -- and not with the messenger. Surely, the government that prides itself on guiding the fate of the world's largest democracy, should not limit free access to information-gathering, however distasteful and embarrassing the data gathered or its interpretation. Even seemingly innocuous issues as environmental protection often hinge on the protection of a people's democratic rights.