Car manufacturers spurring battery research

ELECTRIC cars run on batteries but work best without them. Batteries halve electric cars' speed and range and increase their cost because it is more difficult to get electricity into and out of a battery than it is to pump and burn petrol. With stricter emission controls slated for later this decade in the US, automobile manufacturers are looking for cheaper and better batteries that will run electric cars.

ELECTRIC cars run on batteries but work best without them. Batteries halve electric cars' speed and range and increase their cost because it is more difficult to get electricity into and out of a battery than it is to pump and burn petrol. With stricter emission controls slated for later this decade in the US, automobile manufacturers are looking for cheaper and better batteries that will run electric cars.

By 1998, 2 per cent of all the cars sold in California must emit no air pollution and 10 per cent must be emission-free by 2003. Two states have followed California's lead and ten are considering the move.

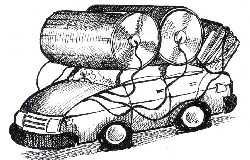

In the quest for a better battery, an option that could beat other contenders for clean technology is the flywheel, a disc on a revolving shaft that can accumulate power. The flywheel has been used as a source of power in satellites and in the US military.

But it has a disadvantage. Because the energy in a spinning object depends on its mass, shape and size, flywheels for cars must be light, compact and spin very fast. Discs made of the strongest material split into fragments at such high speeds and rims that are held on to an axle by spokes separates from them.

American Flywheel Systems (AFS) has worked around these limitations and designed a set of two flywheels that work at speeds of 200,000 rounds per minute. The set can give future cars more range and has a lifespan of more than 320,000 km. Its top speed and acceleration are limited only by the car's circuits, but automobile makers are wary about the price. AFS hopes to produce a prototype by 1994 but needs $ 10 million for it. The company is confident that once production begins, the economies of scale will lower prices to competitive levels.

Car makers are also investing in the search for new and better batteries. Manufacturers have roped in the United States Advanced Battery Consortium (USABC) for a four-year, $ 260-million battery improvement programme and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) to work out how electricity can be supplied to half a million cars within 10 years.

However, the USABC has restricted its search for a better battery to medium- and long-term work on chemical batteries. It also wants battery makers seeking consortium financing to surrender patent rights of products they come up with. So far, the SABC has awarded a contract to a Michigan firm to make larger versions of nickel metal hydride batteries used in laptop computers and cellular phones. These batteries can power cars twice the distance lead-acid ones being used now can, but are much costlier.

Other alternatives

Research outside USABC has sprung up some encouraging results. Ford, BMW and Volkswagen are counting on molten sodium-sulphur batteries that produce a great deal of power. However, these batteries freeze at temperatures below 300oC and require expensive insulation and technology to keep the chemicals in a molten state. They also drain their own power and require frequent plugging.

Electrosource, a Texas company, has improved upon the lead-acid battery to provide twice the power, twice the lifespan and one-fourth of the recharge time at less cost. The Japanese are experimenting with nickel-cadmium batteries that have higher capacity, long life and quick recharge. But its costs and the dangers to the environment by cadmium are likely to put off US buyers.

All chemical batteries that will be manufactured in the next decade are likely to have limited range, slow acceleration and expensive replacement. The flywheel appears to be the most profitable option that can meet the tough anti-emission standards. Already there are signs that by the time batteries match the flywheel's performance levels, other technologies will be in the competition. Low-emission fuels are being sold widely. Buses in Hamburg are powered by hydrogen and those in Washington use electricity from fuel cells.