A Tale of Two Rivers

NOYYAL and Bhavani. Rivers both. One is dubbed dead. The other is one of India"s most polluted rivers. One is seasonal, the other perennial. Both emerge from the Western Ghats and empty into the Cauvery in Tamil Nadu. The two rivers may be minute in size as compared to great Indian rivers, but have all ingredients of a riveting contest between use and abuse; between desperate and sustainable development.

NOYYAL and Bhavani. Rivers both. One is dubbed dead. The other is one of India"s most polluted rivers. One is seasonal, the other perennial. Both emerge from the Western Ghats and empty into the Cauvery in Tamil Nadu. The two rivers may be minute in size as compared to great Indian rivers, but have all ingredients of a riveting contest between use and abuse; between desperate and sustainable development.

The issues that confront both the river basins are similar: limited water availability; multiple users; severe industrial pollution; confrontation; and legal action.

The Noyyal basin, polluted by the 800-odd dyeing and bleaching units of Tirupur, is a ground for confrontation between agriculturists on the one hand and the textile processing industry on the other. The former cannot use water from the river as effluents have been drained into the river for years.

In the Bhavani basin, the courts have directed the main polluting industrial unit, South India Viscose (SIV), to install appropriate pollution treatment equipment. A coalition of downstream users, incluling the agricultural community and residents of towns situated along the river, threaten "severe resistance" if the industry is allowed to operate, even after installing pollution control equipment. The dispute is all set to reach critical mass by year-end.

The Noyyal Merely 173 km-long, the seasonal river essentially carries untreated sewage and industrial effluents from the towns of Coimbatore and Tirupur for most of the year. With no freshwater for dilution, the untreated sewage and effluents severely contaminate groundwater. As it is, the area is rainfall- deficient.

Orathapalayam dam, the only source of surface water, is a cruel joke. Commissioned in 1992 at the cost of Rs 20 crore, the dam was to irrigate 5 per cent of the land in the Noyyal basin. But quality of water is so poor that it cannot be used. The farmers of Karur taluka, potential users of this water downstream of Tirupur, do not want anything to do with water stored there. Instead, a public interest petition was filed seeking action against industrial pollution.

And in what will surely go down in the annals of "environmental judiciary" as an truly remarkable judgement, Tirupur"s industry has been asked to pay for a complete clean-up of the dam - its water as well as the bed of the reservoir. Industry is also under judicial orders to set up common effluent treatment plants (CETPs) by November 23. These are to be run by independent private sector companies.

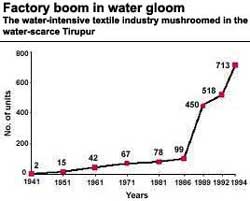

"If this deadline is not met, we will lodge a criminal complaint against industry," declares P R Kuppuswamy, the Karur-based advocate who has filed the petition. He says the state government is not interested in the damage caused by the industry. He may not be wrong. In its eagerness to develop Tirupur, the state government delicensed trade. Encouragement to a water-intensive industry in a water-scarce region explains the state government"s priorities (see graph: Factory boom in water gloom).

Tirupur"s dyeing and bleaching units earn the nation"s exchequer more than Rs 2,000 crore in exports. When export earnings reached this astronomical figure in early 1995, there were only two engineers of the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB) responsible for enforcing environmental norms on about 800 bleaching and dyeing units in Tirupur.

The rapid growth of Tirupur"s industry led to a strange phenomena: a dry river when it snaked into Tirupur, the Noyyal had a flow worth speaking about by the time it came out of the industrial township.

"Approximately 90 million litres per day (mld) of water is used and discharged from the dyeing and bleaching industry in Tirupur," notes Anna Blomqvist of Linkoping University, Sweden, in her book Food and Fashion.

Reportedly, many farmers have abandoned cultivation, opting for vending water, a less risky enterprise with better returns. About 450 water tankers are estimated to ply in Tirupur, only 200 of which are registered with the municipality.

Chemical concoctions

The bleaching and dyeing units use bleaching liquids, soda ash, caustic soda, sulphuric acid, hydrochloric acid, sodium peroxide, and various dyes and chemicals. High concentrations of calcium, magnesium, sodium, and chlorides have also been noted in studies carried out in the basin. Consequently, the river water is highly saline. Groundwater has also become brackish and considerably harder over the past 10 to 15 years.

K Ramachandran Of TNAU"S Water Technology Centre ascribed this high salinity to the varying amounts and kinds of processing chemicals that are used by the textile industry. His 1994 thesis noted an accumulation of heavy metals, finding lead to be above the critical limit. The environmental costs of T-shirts, a paper prepared by Gunnar Jacks of the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, and A Selvaseelan of the TNAU, raises the same problem: "The discharge of chemicals from this production causes local salinisation of groundwater and excessive salinity of the run-off which can no longer be used for irrigation."

Also, the involvement of numerous government agencies complicates the issue further. "The issue is not looked at in a holistic way. If polluted wastewater affects agriculture, it becomes a problem that the irrigation department is to look into and not the TNPCB. Similarly, when the polluted water affects (drinking) water users, it becomes an issue for the public works department and not the TNPCB," says Paul Appuswamy, director of the Madras Institute of Development Studies, Chermai.

The Bhavani

After coursing through 217 km through Tamil Nadu"s Coirnbatore and Erode districts, Bhavani merges with the Cauvery at Bhavani town. The Bhavani sub-basin constitutes 7.58 per cent of the Cauvery basin. The river and its canal systems irrigate about 99,000 hectares. More than 90 per cent of the water is used for agriculture; industry takes 5 per cent; and domestic use is only I per cent.

However, the 5 per cent used by industry threatens the remaining 95 per cent of Bhavani"s waters.

"There will be severe resistance if the pulp unit starts," observes S Sathisundari, president, Bhavani River Protection Joint Council (BRPJC), a citizens" watch-dog committee. She is referring to the pulp unit of South India Viscose (SIV) at Sirumugai. The unit is closed right now as it is upgrading its effluent treatment plant following court orders. A multi-project private sector undertaking, srv is the largest industrial outfit in the Bhavani basin. It withdraws about 50 mld of water - 56 per cent of total water withdrawl by industry in the entire basin. It also returns 41 mId of wastewater into the river.

Though SIV has an ETP, the paper and pulp plant discharges wastes with high organic content and sulphur-bearing compounds. All this collects at the Bhavanisagar dam downstream of the plant. Data collected by the Tamil Nadu fisheries department between 1971-72 and 1996-97 indicates disappearance of certain fish species.

The movement against pollution in the Bhavani started after production capacity at SIV increased from 50 tonnes to 300 tonnes in 1993-94. The country-side was under siege: groundnut production had reduced, as had the protein content of foodgrain. Sugarcane, paddy and onion crops were affected by the poor water quality. Fish catch at Bhavanisagar dam reduced despite the presence of a hatchery.

On May 9, 1994, a great swell of people held a dharna in front of SIV. This was followed by a meeting with the district collector where BRPIC members demanded action from district authorities. Over one lakh signatures were collected at a subsequent signature campaign. The campaign became an election issue, Documented evidence A study on water pollution in the Bhavani Basin by the Centre for Water Resources, Anna University, notes: "Some of the pollutants like phenols, tanin, and lignin and metals are recorded beyond the guide levels." It adds that water users had reported intestinal and pulmonary disorders. The impact of water quality on fauna and flora is also significant. The Kalingarayan channel has a high sedimentary metal load. The Stranger, a Greenpeace report on health impacts of using industrial chlorine, says that the large volumes of organic-rich effluent released by siv was contaminated with a complex mixture of primarily phenolic compounds. "The toxicity of nonylphenol (one of the compounds isolated from the effluents)... is still relatively poorly understood. It has been recently demonstrated that... nonylphenols, can interfere with hormonal systems, specifically binding to the oestrogen receptor in both fish and humans," notes the report.

"The potential effects on human and wildlife population resulting from high volumes of discharges containing nonylphenol and related compounds merits serious consideration, particularly as the effluent is used in arable land," states the report. Adding a word of caution, the report takes note of the fact that treated effluent was encouraged to be used for irrigation. "No consideration appears to have been given to the long-term accumulation of persistent organic pollutants," it observes.

TNPCB action against SIV started in May 1994 when water and power supply to the company were stopped. SIV moved Madras high court. The BRPJC impleaded as a party in the case. On the BRPJC"s appeal for closure of the wood pulp plant, the high court ordered SIV not to release untreated effluents into the Bhavani.

SIV has gone to the Supreme Court, where the case now rests. As of now, SIV has to submit detailed plans of their pulp unit. While they most certainly will be allowed to run the pulp unit if they meet pollution control norms, the Isevere resistance" planned by the citizens" group promises to take this bout between industry and local community to the ropes. Both basins approach the year-end with baited breath. With inputs from Jitendra Verma

Related Content

- Folk filmmaking: A participatory method for engaging indigenous ethics and improving understanding

- Water quality hot-spots in rivers of India

- Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand spar over pollution in the river Ganga

- Excessive water abstraction threatens UK rivers

- China quake: topography can reveal tectonic activity

- What China is doing to Goa