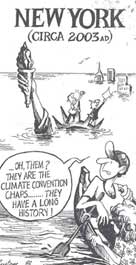

USA may soften its stand on global warming

A HINT that Washington may soften its opposition to measures to curb greenhouse gas emissions was given at the recent session of the Framework Convention on Climate Change in New York.

A HINT that Washington may soften its opposition to measures to curb greenhouse gas emissions was given at the recent session of the Framework Convention on Climate Change in New York.

In an implicit dig at the Bush administration's attitude -- which was widely blamed for watering down the terms of the convention at last year's Earth Summit -- the new US ambassador to the UN, Madeleine Albright, commented: "We are well aware of the disappointment in many quarters that the convention did not go further."

She promised that the US would reassess all options for reducing emissions which many scientists believe are bringing about a potentially disruptive rise in global temperatures, and pledged that it would do its best to prepare a revised national action plan by the next session of the Climate Change Convention in August. Despite this hint of a shift, however, the focus of the meeting centred on the controversial Global Environment Facility (GEF), which was rushed into existence by industrialised countries seeking to pre-empt Southern demands at the Earth Summit for a green fund, and which was subsequently named as the funding mechanism for the Climate Change Convention, as well as for the convention on biological diversity. Differences in the way GEF should operate under the conventions and the way it should operate under its other project work are proving difficult to reconcile.

Although GEF is supposed to be a partnership between the World Bank, the UN Development Programme and the UN Environment Programme, critics claim it is dominated by the Bank and thus by the Bank's Northern funders. As a result of this and other criticisms, a so-called independent review of the GEF is being conducted by a panel that includes senior officials of the Bank, UNEP and UNDP as well as what critics dismiss as "a token representation" of non-government organisations (NGOs).

"The final decision of any role for the GEF must be based on a truly independent review, not an internal review by Bank staff," Bill Hare of Greenpeace International said at the New York meeting, speaking on behalf of the non-government Climate Action Network.

There is also a tussle for power between the GEF and the signatories to the convention, which meet as the Conference of the Parties. The GEF sees itself as supreme, with the convention signatories providing no more than guidance. Many of the signatories insist that they should make the decisions, leaving the GEF with the job of carrying them out.

The GEF secretariat has been stealing a march on the convention participants by working out the technical details for funding while the signatories remain bogged down in working out the details of their role.

But the Group of 77 (G-77) developing countries and China made their point at the New York session by securing agreement that the Conference of the Parties, expected to meet late next year, had the power to review and modify GEF policies relating to the convention. It was also agreed that the chairman of the Climate Convention Committee should take part in the GEF participants assembly, which meets in Beijing next May, and that the GEF secretariat should look into the need for a legal agreement or memorandum of understanding between the GEF and the convention participants. This would clarify where real power lies.

The G-77 recommendation also asked the secretariat to monitor work being done on "agreed full incremental costs", the wording used in the convention as the basis for determining funding. The GEF is attempting to limit funding to the global benefit of a project after subtraction of the national benefits for the country in which the project is based. To do this, it must differentiate between global and local benefits. But developing countries say that "all measures to be funded according to the terms of the convention are deemed to produce global environmental benefits."

This is a major bone of contention, but under the current plans, convention signatories will not even get a chance to discuss the issue before GEF members finalise it in Beijing. The May deadline, however, may turn out to be over-optimistic, because GEF administrator Ian Johnson admits that other problems may take up the whole time of the May meeting, forcing postponement of the incremental costs decision.

A Climate Action Network member spoke for many other NGOs at the New York meeting when he called for a tougher line against industrialised countries for their attempts to limit funding and maintain their control over the GEF, through the Bank. But the international climate is not propitious for tough stands. Said a delegate from a leading G-77 country: "In the current economic climate, we should accept whatever we are getting from the North."

That still leaves the questions of what projects will be financed under the convention and how much money will be made available for implementation. Developing countries argue that money should be made available to pay for all the reporting required under the convention, as well as for measures to mitigate and adapt to climate change, research, information exchange, education, training and public awareness. These activities are not included in the GEF's brief.

Even more problematic, in the year since the Earth Summit, several Northern governments have cut back their aid programmes. "The funds ultimately required are orders of magnitude larger than even the investment programmes of the multilateral development banks, and vastly greater than any replenishment proposed by the GEF," Bill Hare told the meeting.