Breast cancer: Tracking down an elusive killer

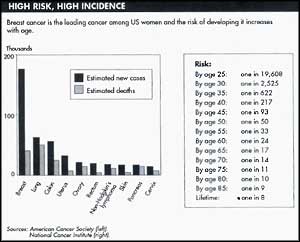

PERHAPS one of the worst fears a woman harbours is that of getting breast cancer, a justifiable fear for, in USA alone, 46,000 women die every year of breast cancer -- and, this rate is increasing by 1 per cent annually.

PERHAPS one of the worst fears a woman harbours is that of getting breast cancer, a justifiable fear for, in USA alone, 46,000 women die every year of breast cancer -- and, this rate is increasing by 1 per cent annually.

Despite the vast amounts of time and money pumped into breast cancer research over the last two decades and the number of theories circulated, scientist are still puzzled about why the disease has increased steadily over the last 50 years (Science, Vol 259, No 5095).

One of the theories put forward 14 years ago was the fat hypothesis. Scientists blamed hamburgers, French fries, bacon and other fatty foods common in the American diet for causing breast cancer. But after a decade of research, one of the many scientists committed to the fat hypothesis, Walter Willet of Harvard University's School of Health, has now concluded there is no relation between fat in the adult diet and breast cancer incidence. Willet had access to data from the largest and best-controlled survey ever done on the topic, the Harvard Nurses Health Study, which included more than 120,000 women.

But some loyal supporters of the fat hypothesis argue that diet during adolescence, when breast tissue grows rapidly, may be more important than adult diet. Others are investigating the possibility that ultra low fat diets could have a beneficial effect not provided by low fat diets.

With the high fat thesis in the fire, scientists have begun knocking at the doors of an old suspect: hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone. Recent research suggests cell proliferation, influenced by estrogen and progesterone, may change normal cells into cancerous ones and thereby increase the risk of cancer.

Noting that women who have had their ovaries -- the major source of estrogen in the body -- removed after the age of 35, rarely get breast cancer, Kate Horowitz of the University of Colorado Medical Centre at Denver says: "The reason that women rather than men get breast cancer is not that women have breasts, but that they have ovaries."

Meanwhile, some scientists suspect the culprit responsible for breast cancer may be lurking in the genes because, according to studies, a woman with a family history of breast cancer runs a high risk of getting the disease herself. Two years ago, Berkeley geneticist Mary Claire King announced she had found the rough location of the gene that predisposes women to breast cancer. Many geneticists found it difficult to believe a single defective gene could account for the substantial number of breast cancer cases, but recent research has vindicated King, showing 5 per cent of all breast cancers is caused by a "corrupted" gene.

One in 200 women inherits the defective gene and those who do, run a 80 per cent risk of developing the disease. Biologists have narrowed the location of the gene to chromosome 17, which also houses the gene for ovarian cancer, and they hope to pin it down in a year or two.

Though most biologists would admit to only a sketchy knowledge of their adversary, they have identified a few chinks in its armour. In particular, they have found breast cancer cells change their patterns of protein production in two major ways: they manufacture increased amounts of protein that stimulates growth and helps the diseased cells to spread to distant organs; and, they simultaneously produce proteins that hamper the body's ability to retard the growth and transfer of the cancer cells.

As researchers identify more of the changes accompanying the insidious transformation of breast cancer cells into malignant ones, a fundamental question that keeps cropping up is: What causes all those changes?

The leading hypothesis right now is that breast cancer results from the loss of one or more "tumour suppressor" genes, which are thought to keep cell growth in check by regulating other genes. The breast cancer susceptibility gene that King and several other groups are homing in on may be one such tumour suppressor gene. Another is the p53 gene that has already been implicated in breast cancer as well as in other types of cancer.

Meanwhile, for the time being, women have to content themselves with intensive screening to detect tumours at the earliest. And hope that biologists will come up with earlier indicators of the onset of breast cancer.