A tale of two states and a river

THE CAUVERY, one of the major interstate rivers of south India, has been both a blessing and a curse to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu: it has helped farmers but also caused discord.

THE CAUVERY, one of the major interstate rivers of south India, has been both a blessing and a curse to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu: it has helped farmers but also caused discord.

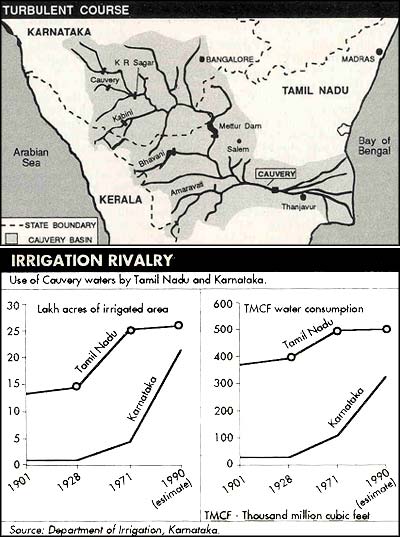

Irrigation from the Cauvery has been more developed in Tamil Nadu than Karnataka. The reason is geological: Whereas the river catchment area in Karnataka is rocky, the delta region of Tamil Nadu is sedimentary. In fact, irrigation in Tamil Nadu dates back to 2 A.D. when the Chola kings constructed a major irrigation channel for paddy cultivation. The Grand Anicut is still a major source of irrigation in the Cauvery delta, including Thanjavur, the rice-bowl of Tamil Nadu.

Under British rule, the irrigation network in Tamil Nadu was extended to increase the cultivation of rice. However, irrigation development in Karnataka was kept under strict control. Diehard supporters of Karnataka's cause in the Cauvery dispute, such as former state irrigation minister H N Nanjegowda, say this was because of "the stout Kannada resistance offered to the expansion of British empire in India, specially in the last quarter of the 18th century under Tipu Sultan".

The princely state of Mysore began making large investments in improving and creating tanks, anicuts and irrigation channels from the Cauvery after the widespread famine of 1877-78. But the British provincial government in Madras forced the Mysore government to a conference, held in Ootacamund (present-day Udhagamandalam) in 1892, where it had to agree that it could not, without prior consent of the Madras government, build any new reservoirs or irrigation facilities from either the Cauvery or other important rivers such as the Hemavathy or the Lakshmanatirtha. In return, the Madras province agreed to limit its use of Cauvery waters to the "prescriptive rights" already acquired. However, these rights were defined very nebulously.

Soon, the agreement became a source of discord. The Madras Province wanted to increase its "prescriptive rights" and the Mysore government argued against the restrictions on the extension of its irrigation facilities.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the two governments formulated schemes to enhance their respective irrigation networks. Gaining currency as the "Madras Cauvery" and the "Mysore Cauvery" projects, they became the source of much bickering between the two governments. The Madras government announced a reservoir at Mettur and the extension of the Grand Anicut to the dry areas of southern Thanjavur. The Mysore state announced a dam at Kannambadi, now called the Krishnarajasagara dam, the brainchild of engineer-architect, M Visveswaraya.

Following extended bickering, the two sides in 1924 agreed to limit their utilisation of the Cauvery waters -- Mysore to a total irrigated area of 97,200 ha and Madras to 729,000 ha.

The 1924 agreement was to be reviewed only after 50 years. Even after Independence, this provision was adhered to. K Karunanidhi, the stormy petrel of Tamil politics and former chief minster of Tamil Nadu, says that "on several occasions we tried obtain a review of the 1924 agreement by the Centre, but were always reminded of its time frame." The review came only through a civil petition before the Supreme Court. In the meantime, the Cauvery had already become a source of much bitterness between the people of the two states.